Four fragments of a portrait of Per Nørgård

By Anders Beyer

In order to understand the basis for Per Nørgård’s œuvre and for new Danish music in general, it behoves us to consider elementary geographical facts and, notably, not to ignore Denmarks position between Central Europe and the rest of Scandinavia. Surveying the works of Danish composers of this century we recognize the musical equivalence of a magnetic field connecting patterns of thought in Central European modernism with a particular Nordic: frame of mind, one that is dominated by the concepts of attraction and repulsion.

Subject to influences from both sides, Danish composers have long been sandwiched between the continental periphery and the centre. While this situation has generated productive discussions among Danish composers in search of their own identity, it has also entailed a profound scepticisru vis-a-vis the dogmatic view of Central Europe as the musical centre of the entire world and, paired with this, a firrn belief in the distinct character and valuable contributions of Danish music.

Like Nørgård, other composers of his generation – Pelle GudmundsenHolmgreen, Ib Nørholm, and the slightly younger Ole Buck – reacted to the new music coming from the south by simply going against it; in response to compositional complexity, they wrote extremely simple music, so initiating the period of ‘New Simplicity’ in Danish music and contributing a uniquely Danish note to international minimalism. Although these composers later adopted different musical approaches, their typically Danish attitude prevails: nothing from the outside is accepted uncritically; rather, everything is rejected at first and eventually reconsidered subject to close scrutiny.

As a teacher of composition at the Royal Danish Academy of Music, in Copenhagen, and subsquently at the Royal Acaderny of Music, Århus, (until 1995, when he retired as a professor to pursue full-time composing), Nørgård let this Danish fondness for open discussion influence his way of teaching and so made a significant contribution to the development of musical aesthetics in Denmark and, by extension, the Nordic countries. No less important, in this respect, were the seminal ‘debate club’ meetings held (most of them) at his home in Copenhagen: an informal 12-year seminar with participation by composers, theorists, performers, writers, and others. In this way Nørgård taught and practiced free thinking to a generation of younger composers (Hans Abrahamsen, Hans Gefors, Bent Sørensen, Anders Nordentoft, Karsten Fundal, Svend Hvidtfelt Nielsen, and others). His motto was apparently, consider your teacher a sparring partner not a model to imitate – agree to disagree.

Nørgård epitomizes the perpetual dialogue between. north and south. Early in his career he shut out the chaotic sounds from the south and turned to the ‘universe of the Nordic mind’, a love affair with the Nordic tone in the wake of Vagn Holmboe and Jean Sibelius. However, Nørgård’s inquisitive mind soon rejected this compositional credo as also limiting, and he broke away to explore the New Music scene of Central Europe that in turn provided him with materials for the development that followed, a process that increasingly led him to accept conflict as an inherent condition of music.

The two extremes of something easily perceived and something very complex always intrigued Nørgård; tensions between opposite tendencies have been a characteristic of his work since his earliest pieces from the 1940s. He generates fields of tension by confronting familiar and unfamiliar expressions, by opposing something simple with something advanced, or, by allowing banality to encounter wisdom. In Per Nørgård’s music disruption is as significant as coherence; rambling madness and free imagination is as important as conscious control. Balance is the key issue: between what is known and what is unknown; between the clear and the mysterious; between past and present. In the 1960s he wrote collage-type music full of recognizable quotations from near and far; later the quotations were veiled and gave way to a musical play on suggestions and associations.

As a student of Vagn Holmboe, Nørgård knows the traditional ideal of balance in music, the equilibrium between apollonian and dionysian powers, to use Holmboe’s terms. Nørgård talks about yin and yang, about rationality and irrationality, and also about the interplay between the right and left halves of the brain, with the result that we may add yet another pair of opposites that influence his creative work with aesthetic form, namely, the relationship between tradition and innovation. We hear it in his music as a tension between idylls and catastrophies, between the outdated and the futuristic, between regional and global orientations. Hans Magnus Enzenberger’s characterization of Norwegian mentality fits Nørgård well: on the one hand, a love of anachronisms and a stubborn clinging to pre-modern ways of thinking and living; on the other, an instinctive disposition for anticipating the future; provincials and cosmopolitans, both.

In that light it is not unreasonable to designate Per Nørgård as Carl Nielsen’s most visible heir. Nørgård’s music is, in that respect, as thoroughly Danish as possible and indeed placed in direct continuation of Nielsen’s aesthetics with Vagn Holmboe as artistic mediator. These composers grew up in a Danish/Nordic universe of tones resonant with classicist aesthetics. In Nørgård’s case, however, something else is added, new light is thrown upon the inherited treasures, and nothing escapes being exposed to new principles. It seems that T. S. Eliot’s formulation applies to this process: the tradition has not been added to, it has been altered. But then, this is only one side of the issue. The other is a striking succession of distinct phases of a development that traces Nørgård’s linear progression from the Nordic period of the 1950s, through the pluralistic universe of the 1960s, the infinity world of the 1970s, and the existential chaos of the 1980s, to the reoccurring hierarchies (‘tone lakes’) of the 1990s. In each decade Nørgård focuses in an almost monomaniac vein on new concepts that, nevertheless, turn out to hark back to earlier methods as the necessary means for realizing new discoveries. In the composers own words:

The new can only be achieved by means of that which I once rejected. This is actually the reason that I never burned any bridges. My earlier inventions keep coming back saying, ‘don’t you need a bridge here?

Per Nørgård in conversation with the author, July 1995

INTERFERENCE, IN LIFE AND IN MUSIC

‘Correspondances’ is the tide of one of the poems in Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, a poem about the cross-relations between man and the universe, and between colours and sounds, as well as associative connections between sounding structures. In the same spirit one may comprehend Nørgård’s music as essentially deriving from contacts between elements of different nature. This may take the form of trivial day-by-day realities showing up in the middle of an austere passage of a symphony, such as it happens when the banal tune of Jingle Bells suddenly pops up in the Fifth Symphony. Calculation and spontaneity, structure and freedom, construction and expression – in Per Nørgård’s universe both poles are constantly considered. We may as well use the terms yin and yang, for oriental philosophy has a place of honour in Nørgård’s world.

The tensions in Nørgård’s music originate in these contrary tendences or, to use the composer’s own word, they (the tensions) portray the interference between distinct categories of materials. Healing, holism, fractals, and metaphysics are but some of the components of a world view with unlimited possibilities for expansion, and, over the years Nørgård has indeed expressed his opinions – verbally or in writing – regarding just about any conceivable subject. Precisely because everything conceivable is of interest to him, any subject may become part of his universe, which, however, is not to say that he subscribes to John Cage’s aesthetics of chance. The balance between system and chaos, between rational and irrational, remains a characteristic feature of the composer’s production but without ever implying any tendency toward a philosophy of the middle-of-the-road; in fact, Nørgård persistently violates both the boundaries of ‘good taste’ and his own definition of his artistic ego, with resultant experiences of disruption and re-orientation of the self.

His attitude to this process is expressed in the following statement (in an interview with the author, 1995):

It was the cultural claustrophobia that got me started as a composer. I was seven years old when the Second World War knocked on the door, and times were not for poetry and sensitive humanism. I grew up at a time when law and order ruled the day, at school too. That was a frightening period, like a prison. The experience of something else beyond the surrounding walls has always been vital to me. I find it fascinating that the right and left halves of the brain concern themselves with two essentially different areas; that is rationally satisfying. The polar opposites of rational and irrational have preoccupied me quite a bit. To eliminate the irrational side from our lives would lead to criminal behavior like we saw with nazism, which to a great extent was based on frustrated irrationality. Every day we make use of both the irrational and the rational parts of our consciousness; therefore, music must embrace both.

Per Nørgård in conversation with the author, July 1995.

The composer’s ability to insert fractures and strangely unmotivated ideas into the musical fabric while maintaining the sensation of a progressive development is rooted in his desire to vary the traditional basis in order to effect changes of accepted rules, to obtain a freedom such as Mozart was able to achieve precisely because his music rested on a traditional foundation. In Nørgård’s case it is, therefore, not meaningful to talk about a sequence of modern and post-modern tendencies or sources of inspiration, because they co-exist, at least in the sense that Jürgen Habermas ascribes to ‘modern’ and ‘post-modern, namely as two simultaneously occurring responses to the phenomena of the modern world from its historic beginnings to the present. Consequently, Nørgård’s music takes no unequivocal stand with respect to the discussion of genres and schools, but maintains the tension between extremes and avoids reducing the musical expression by simplification or elimination.

Nevertheless, a recent (1994) statement by the composer (see Dansk Musik Tidsskrift No. 4, 1994-95, pp. 179-180) reads as an acknowledgement of his belief (as a composer too, one infers) in the ‘great stories’ much spoken of in today’s intellectual debate. In this, then, he would seem to be in line with the Central European modernist understanding of history and philosophy (never doubting for a moment the validity of enlightenment and reason; c.f. Adorno’s concept of an ‘objective tendency’ inherent in the (musical) materials). Nørgård’s œuvre (though not finished yet) does give the impression of being/becoming one such ‘story’. As a narrative it is rich in detours and asides, and all those small, ‘meaningless’ or ‘disturbing’ stories within are significant in their own right, I think. Not only art and kitsch but also debased art and elevated kitsch belong in Nørgård’s world as a 20th-century composer. His music is ‘scarred’, and the scars constitute the form, much like in Mahler, that supreme master of constructive collapse. Common to both composers is the narrative quality of their music, a musical prose presented in so many volumes, music with the epic and never-finished aspect of novels. Not even the composer himself knows what will happen when he turns the next corner: the main character may die; or a supporting character take the stage, demanding our full attention.

Composing in this manner implies frequent revisions of old achievements; the composer will recall works, return to old paths that now are traced with new insights, or re-work pieces, as happened when the opening of the Fifth Symphony was rewritten. It also implies that certain works are best seen as studies for more significant works, for Per Nørgård’s artistic universe is coherent from the first work to the most recent and thus, in effect, is one huge work-in-progress. This constitutes a paradox in that the composer, over the years, has experienced incessant breaks of continuity in his pursuit of experiences that transgress personal limits; however, there is an overriding desire to express himself behind all these excursions into new methods of constituting form and connecting rhythms, timbres and tones.

From this view the unexpected disruptions and impulses are seen as experiments with new musical worlds. The latest example of this process is recorded on Gert Sørensen’s CD, A Drummer’s Tale, on which Nørgård improvises as vocalist and as synthesizer player:

I have repeatedly been asked to improvise in public, but have said no. The percussionist Gert Sørensen and [the trumpeter] Palle Mikkelborg, the producer of the new CD, were confident that I had the resources for improvisation. Their trick consisted of placing me alone in the studio in order to capture the moment. I was able to determine the tempo, and the recording equipment knew how to start and stop. My instrument was a Jupiter 8 synthesizer, the same I used for the sounds of the opera Det guddommelige Tivoli (1982). It can create a rich and wild world, where some sounds resemble a hippopotamus vomiting, others falling stars à la Disneyland, others again dry harpsichord timbre, etc.

Nørgård in conversation with the author, July 1995.

The double CD, A Drummer’s Tale, is released on dacapo

(8.224.024-25).

On this CD recording Nørgård is improvising against a background that builds on acceleration, a technique he used in the string quartet Tintinnabulary (1946). The composer improvises at the grand piano and vocally; at the synthesizer he creates phantasies based on phase shifts, multiple layers, and on downright absurd disruptions of all elements. In his own words: “When improvising, I choose a method of playing with a wide enough spectrum of ambiguity so that I am never bored myself.” This might involve tension between two opposite principles, for example, or between two incompatible experiences of pulsation; even chaos versus order. The possibilities are endless, for Nørgård’s world is as unpredictable as life itself; nothing is taken for granted, everything is subject to exploration.

HELLE NACHT: A CASE IN POINT

As of now, Per Nørgård has composed three concertos for solo string instruments and orchestra: Between for cello (1985), Remembering Child for viola (1986), and Helle Nacht for violin (1987). The titles are not accidental, for each refers to something that is essential to the specific work, whether it is a mood or a principle of construction, or both, as in the case of Helle Nacht. Precisely the relationship between expression and construction is the ‘motor’ of the present essay as I shall attempt to explain the expressions and moods of the work with respect to its formal construction.

Per Nørgård has worked a great deal with perceptual phenomena, our experience of structural connections; undoubtedly, issues of musical information are crucial to his works. Typically he will raise questions such as: “How much information and how many different layers can the ears perceive?” We find him struggling with such problems in Helle Nacht.

The title (meaning ‘Light Night’, a quote from a poem by Heinrich Heine) evokes an interweaving of opposites: the night is dark, yet light. In his foreword to the published score Nørgård explains the title thus:

I chose this title Helle Nacht for my violin concerto because it describes both the mood and the texture of the four movements; on the one hand, melody, timbre and rhythm are always transparent and delicately knit (‘light), on the other hand the transparency is ambiguous (night?) like a turning prism, allowing the listener to experience different layers in the music with each hearing.

This description provides a ‘key’ to the work, one that eases access to secrets that might not be accessible at first hearing. We will not penetrate far into Per Nørgård’s musical universe without paying attention to the phenomena of perception. As we can assume that the composer wishes to communicate with his audience, we may expect his music to provide for some kind of ping-pong game between transmitter and receiver. The composer sends his signals in the form of his personal language and – if all works well – we can follow his thoughts and share his visions.

Throughout his career Nørgård has been conscious of this transmitter/receiver function in music, and it is indeed remarkable that the works for soloist and orchestra occur so relatively late in the composer’s worklist. He had to complete the works of the 1960s/1970s, the innovative experiments with musical materials and the grappling with urgent existential questions (notably, in the body of works inspired by the schizophrenic artist Adolf Wölfli), before he could begin to work on solo concertos in the late 1980s. It may be argued that Helle Nacht not only constitutes a summary of experiences gained in the many works that precede it, but that it also marks a turning point in Nørgård’s musical œuvre.

With this work he has, so to speak, placed himself in a position of merging his own experiences with twentieth-century musical achievements at large. Jørgen I. Jensen has described the composer’s new situation in the light of the violin concerto:

It is as if Per Nørgård now is writing his way out of the entire twentieth century in the form of one unified stream – as if the many and widely different rhythmic and melodic layers in the work have set the twentieth century’s musical universe in new motion, rendering it intelligible as a psychic experience, as new mental activity, a new individualized perception.”

Sleeve notes for CD recording of Nørgård’s Helle Nacht (EMI 7 49 869 2)

In the course of a musical development that has taken many years and has gone through a multitude of expressive forms, the problem of perception has remained a constant. Any composer with something to communicate must continually ask a series of diagnostic questions. Some of these concern information density and lead the serious composer to pose such questions as, “How much information can I assume that the ear will be able to perceive?” or, “How complicated can structures and varied layers within the music be if the ear is to be able to capture them?” and, even broader, “For whom am I writing, and why?” And we, the listeners, may ask ourselves whether it is necessary to know a lot about the construction of the music in order to listen with pleasure. These and other questions are highly relevant in the context of Per Nørgård’s music, and his means for tackling the problems they raise will be noticed by the absorbed listener or the attentative reader of the scores.

The violin concerto Helle Nacht has been recorded on CD and the score has been published, so that we, only a few years after the premiere performance, can immerse ourselves thoroughly in both sound and notation. At this point I will look closely at only one movement of Helle Nacht, the five-minute long third movement [recorded on the sampler CD, ed.]. It is constructed around three melodies that constitute three distinct layers of musical meaning: a prayer (the Gregorian tune Te lucis ante terminum that Nørgård also used in the viola concerto), a place (the quasi-pentatonic Scotch song Loch Lomond) a time (the Danish song En yndig og frydefuld sommertid, (A lovely and joyful summertime)).

As Nørgård creates his layered melodies and rhythms, he takes care to keep them separate, so that it becomes possible to hear distinct musical levels. The layers are not separated demonstratively, but reflect an ambiguity that is part of the basic concept of the work. After repeated hearings, a well-known motive may suddenly emerge from a context that before sounded strange. The experience is somewhat like looking at the popular 3-D Magic Eye books: after a while a familiar image jumps out from a surface that at first showed only unclear forms. That is how the third movement of Nørgård’s Helle Nacht functions – as ‘magic ear’ music.

Examples 1, 2, and 3 show the melodies (in the keys in which they occur in the Violin Concerto), and evidently Per Nørgård here is setting up a situation in which he can assume that the listener will be familiar with at least one of the three melodies. The composer can then, as we shall see, play on different combinations of these materials. An important question in this context may be: “What do we hear in the foreground and what do we hear in the background?” or, “What did the composer want to place in the front of the sound picture as something crucial, and what did he want to leave in the background as less essential?”

In spoken language it is not possible to say two things at the same time, but in music it is. In music two phrases or expressions can sound together and at one and the same time live their independent lives and supplement each other; thereby musical stories can unfold in multiple dimensions, so that they alternatingly can be foreground and background for each other.

In the third movement of the Violin Concerto, Per Nørgård attempts a fluctuation between the three layers, a continuous alternation between foreground and background in the course of which he can play upon the familiar versus the unfamiliar. By way of very carefully calculated relationships between tempo proportions he is able to avoid the three melodies sounding as if they were right on top of each other, and he makes it possible for the listener to differentiate the melodies while hearing them together. Nørgård is very considerate towards his listeners, both by introducing melodic materials that we are likely to know – at least in part – beforehand and by presenting these materials in such a way that we are able to trace them. But at the same time – and this is just as important – we are also drawn out into deep water, our heads are submerged, and water fills our ears.

We might go further yet and ask, ‘Why does Per Nørgård use preexisting materials?” “Is it because his inspiration and capacity for invention is giving out?” No, it is because he, in the present work specifically, wants to get to the root of our musical culture as a prerequisite for cultivating new musical terrain. It is perhaps here that we recognize the allure of Nørgård’s work, in the way he takes us by the hand and leads us through a landscape that is at once familiar and new. We may be both delighted and disappointed, but when the musical adventure comes to an end, we are somehow changed. In the best sense, we have improved our ability to hear new musical contexts and have achieved new insights.

The third movement of the Violin Concerto is in fact so ingeniously composed that we already at the first hearing might detect, say, fragment of a melody or phrase that seems familiar but which, in spite of being recognizable, is veiled and eludes our consciousness like a wet piece of soap. Repeated listening will train our ears to perceive more melodies and we might even get to the point where we can decide for ourselves just what layer we will follow. In other words, it all comes down to a conscious form of listening whereby we become involved with the gradual penetration of the work’s inner spheres and its construction to the extent that our confidence evolves into a selective participation in the musical process, a making of choices that includes deciding between devoting our attention to one of the three melodies, or to all of them.

In this process the composer again extends a helping hand as he, by means of shifting accents relative to the contexts, continually manages to alter our sensibility. Altered sensitivity is precisely what he achieves in the Violin Concerto, and we shall see how he is able to conduct our ears, so to speak, in accordance with his ideas of what we should be listening for. Per Nørgård’s main concern is multiplicity of meaning, changeability (again consider the contradiction in the title, Light Night), and the experience of objects illuminated from different angles, rather like what we see in a kaleidoscope – suddenly the familiar connections disappear, and new ones take form.

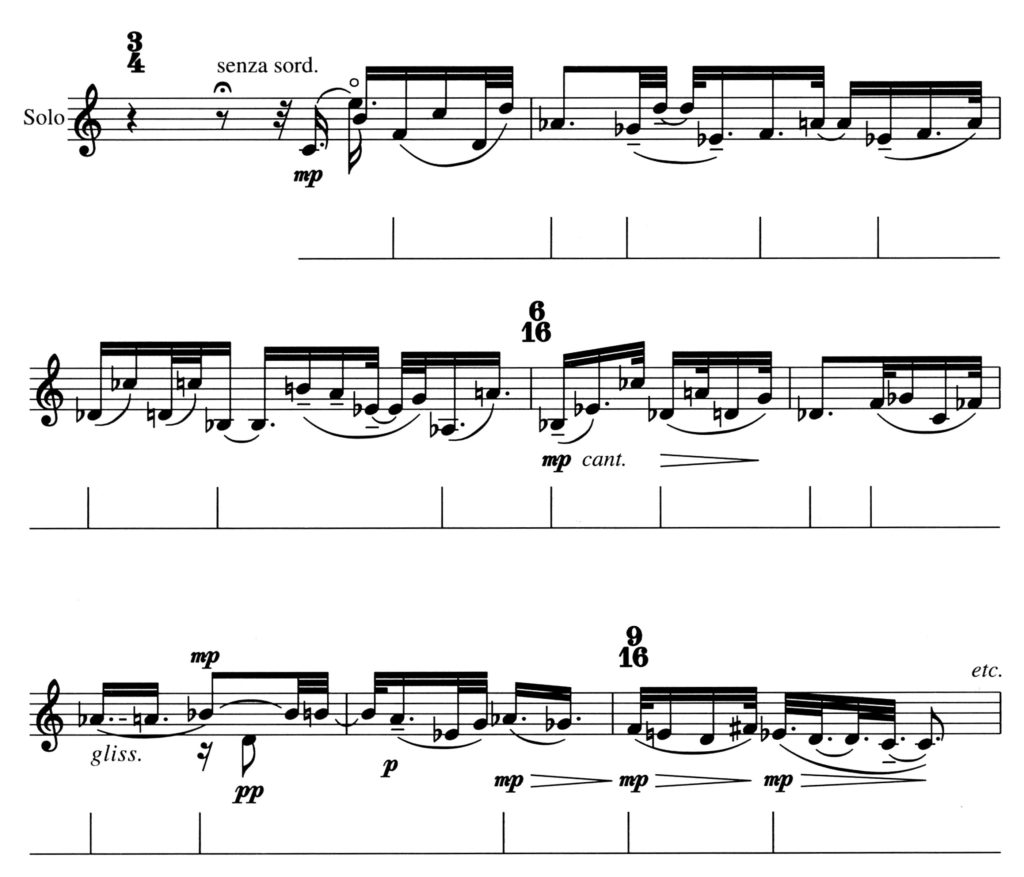

Let us now take a closer look at the third movement. Already at the outset the various layers are presented in the solo part (see Example 4). The three melodies are tightly interwoven, so as to engender a new melody that has a kind of searching and somewhat dance-like character. The first D is the beginning note of En yndig og frydefuld sommertid (designated as the third layer in the example), while the soloist here starts Loch Lomond on the A flat on the first beat of the second measure (designated as the second layer), and the Gregorian chant begins in the first measure on B flat (marked as the first layer). Notice that even though the three melodies are independent, the one melody that arises as a result of the amalgamation of the three possesses the highest priority; it is an autonomous creation with its own distinct character.

Furthermore, we observe that the keys of D flat major (Loch Lomond) and G major (En yndig og frydefuld sommertid) have a complimentary tritone relationship, facilitating differentiation of tonal events.

In the first two systems of the score we see the piccolos playing Loch Lomond a fifth above the soloist’s version, while the clarinets play ‘Te lucis ante terminum’ the interval of a third removed from the performance of the same melody in the soloist’s part. The rest of the orchestra, that is the string section, presents a diluted version of what is taking place in the solo part; in other words, the string section plays materials derived exclusively from the three melodies contained in the soloist’s part, to the effect that the orchestra provides a kind of sustained echo of the soloist.

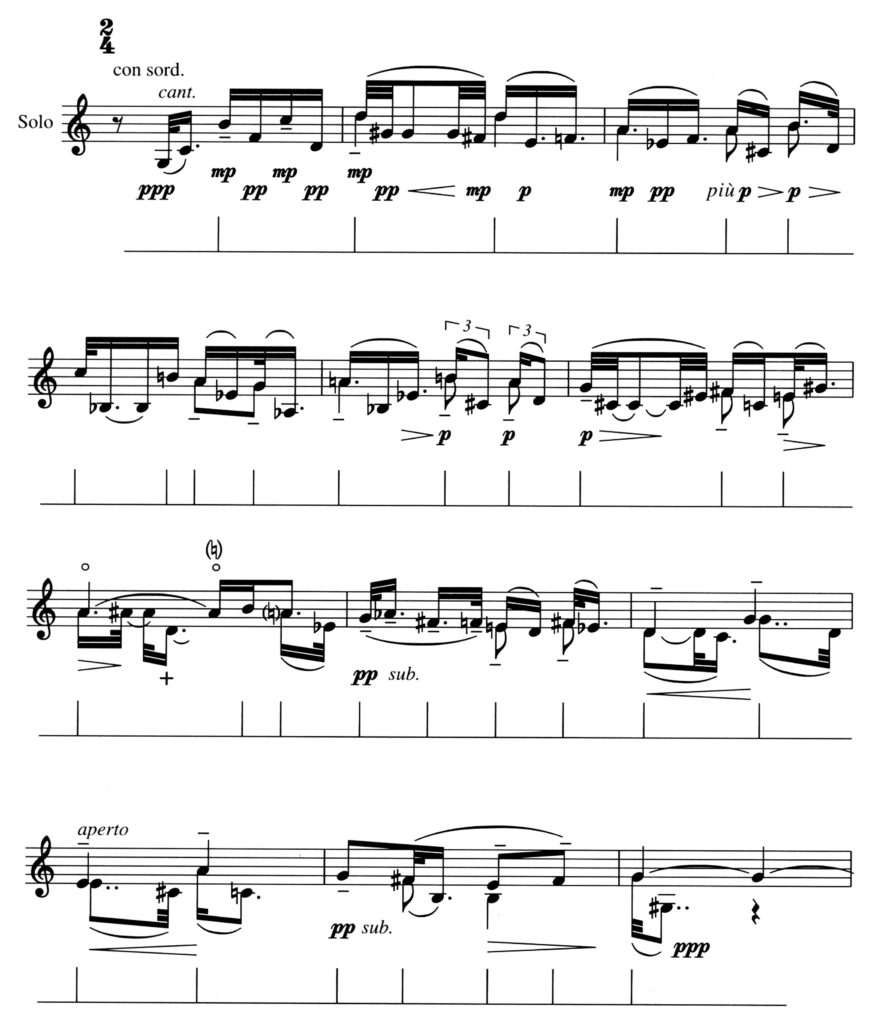

Shortly before the end of the movement, there are three recapitulations or more correctly speaking, extracts, of the three melodies, all played by the soloist in such a way that the three layers are brought into focus one by one. The composer achieves this effect through select accentuations: in the first recapitulation he focuses on the Loch Lomond layer, notating the melody so that the beginning tone is the upbeat to the accented first beat on which the melody’s second tone, A-flat, falls. See Example 5. The next time around, Te lucis ante terminum appears in the foreground represented by the second strophe of the song. See Example 6. Finally, we hear a beautifully ornamented rendition of En yndig og frydefuld sommertid, with the piece’s B-section on the accentuated beat. See Example 7.

In this movement, Per Nørgård translates an experience of nature into music. Possibly he was inspired by the characteristic intensity of the dimming light on a Nordic summer evening, the mysterious moment when light and darkness are interwoven and in equilibrium – the ‘light night’ of the title. The musical techniques employed serve to generate fluctuation, vibration, presence, as the soloist’s voice emerges from the transparent movement and submerges itself in the musical flow, now tense, now released. Soloist and ensemble breathe like one; scenes of nature at dusk are glimpsed as through a veil: ambiguity is the essence of the musical continuum.

The movement is effectfully terminated with an ‘Amen’ played by the flute. It is derived from the Gregorian chant Te lucis ante terminum, translated: ‘Before the light is out we beseech thee’ The evening hymn’s theme of closure and departure brings the movement to a natural end.

It is customary in discussions of classical solo concertos to speak of the soloist and the orchestra as representing the individual against the collective, and to expose the dynamics of the genre as deriving from a battle between the two sides, but Helle Nacht is not characterized by such scenes of strife. Rather, we have an ambiguous, unsettled situation in which the soloist is partly incorporated into the orchestral texture, partly insisting on a measure of independence as an autonomous ‘I’. One might say that the work is about this soloistic ‘I’ who gathers inspiration from the (orchestral) surroundings, and vice versa. The surrounding orchestral timbres ‘rub off’ on the soloist, who tells the story of the encounter in individual terms.

The refined, delicate air of a hushed natural scene that serves as inspiration for the music does not call for violent orchestral sounds. Consequently, the orchestra is small and Nørgård favours the shimmering play of strings over boisterous percussive effects. In a mere five minutes the composer manages to build up an entire micro-cosmos, but as indicated, this world is tightly related to the other worlds, that is, the other movements, of the work. The second movement, for example, is a kind of mirror image of the third, and both are wrapped in the outer movements that, on their own terms, establish other entities, other relationships.

The paradox of the third movement is that it, the heterogeneous materials notwithstanding, is composed in linear progression from beginning to end, according to a larger form that was mapped out in advance. The composer’s accomplishment lies in his ability to play with – and against – traditional devices, as well as in his technique of maintaining the tension between freedom and necessity.

In a wider perspective the Violin Concerto demonstrates Nørgård’s determination not to let his choices be dictated by any fashionable aesthetic theories or any procedures that have established themselves as normative in the course of this century. Rather, he lets himself be guided by his immediate intuition for form and contents, allowing stories from far away and long ago to intercept the process. In the third movement, this is what happens through the amalgamation of the three old melodies, but though all the musical materials are derived from these three melodies, they are not used in simple collage fashion. The composer’s art interferes: the melodies are not slapped on top of each other, rather, they are composed together, interwoven according to ingenious systems and techniques with the result that expression and construction become two sides of the same matter.

NEW WORLDS

Helle Nacht may also serve to illustrate the progressive development of the infinity row toward Nørgård’s recent ‘tone lakes’ Except for Tintinnabulary, the Violin Concerto (first and fourth movements) is the first work to employ this new compositional technique.

There is a close connection between the inter-weaving of three melodies in the third movement of Helle Nacht and the idea underlying the ‘tone lakes’, as both articulate the composer’s fascination with ambiguity. We are well informed about this aspect of the new technique through Nørgård’s published commentary to the computer print-outs and computer-generated recordings submitted to him by music theorist Jørgen Mortensen.1 Mortensen’s work showed that any ‘tone lake’ within its circuit of unified melodic materials contains a wealth of sub-melodies (which in turn contain sub-melodies).

Although the sub-melodies of the third movement of Helle Nacht consist of pre-existing material, objets trouvés, the process of connecting them into one melody (with its own complex rhythm), is in principle a manifestation of those row formations that Nørgård derives from his expansive projections of the infinite row and which he calls ‘tone lakes’. It is a significant feature of a ‘tone lake’ that it feeds a fractal process, generating a variety of melodic layers that coexist in such a manner that the tones of one never are intoned simultaneously with those of the others.

This is not the place for an exhaustive description of the ‘tone lakes’,2 an undertaking that, in a sense, could not be achieved no matter how much place was available, because the subject by its very nature is inexhaustible and the potential fund of melodic characteristics far exceeds the most comprehensive description feasible. However, a summary of the phenomenon may suffice as a general introduction.

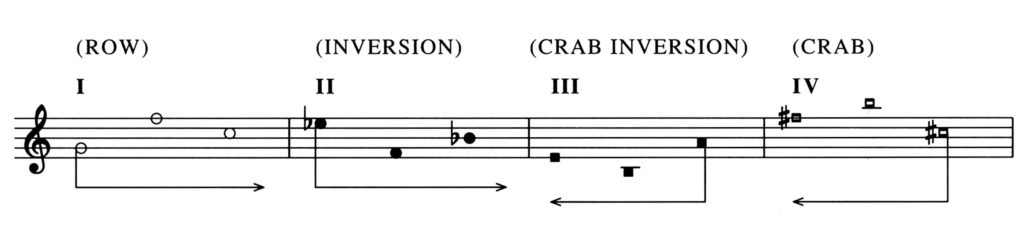

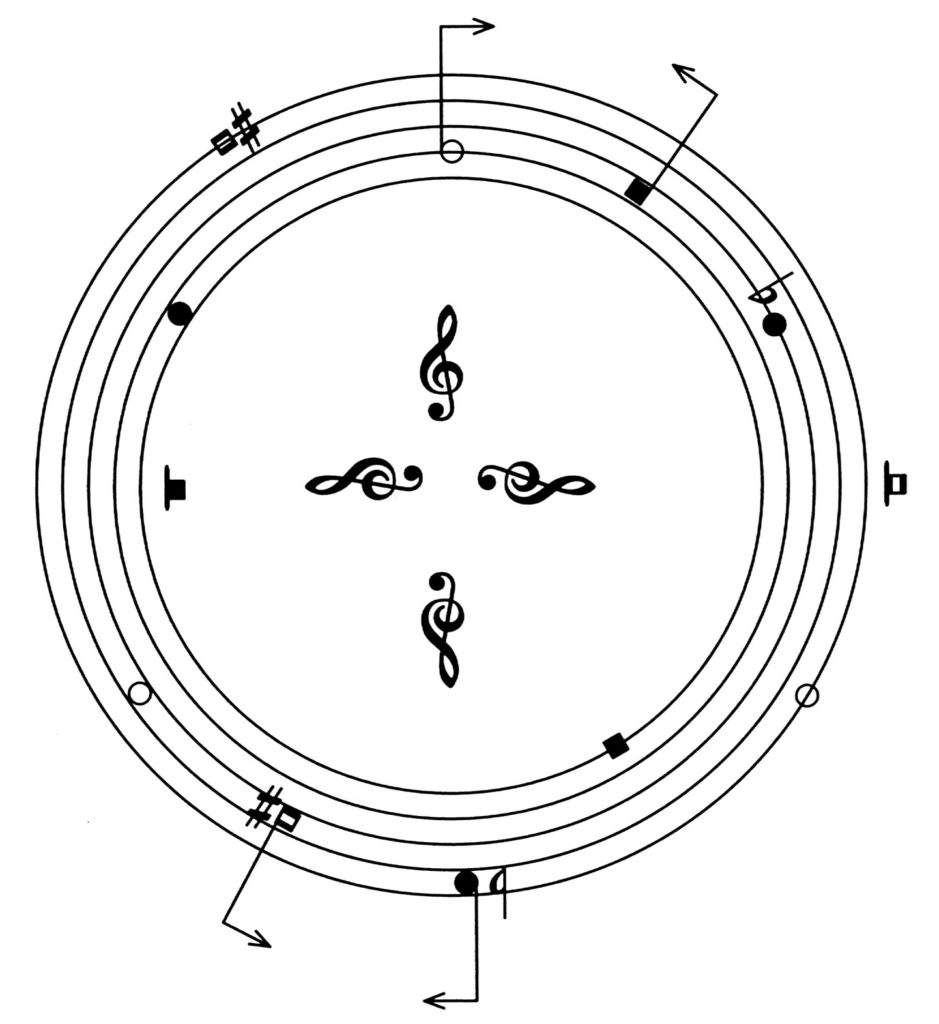

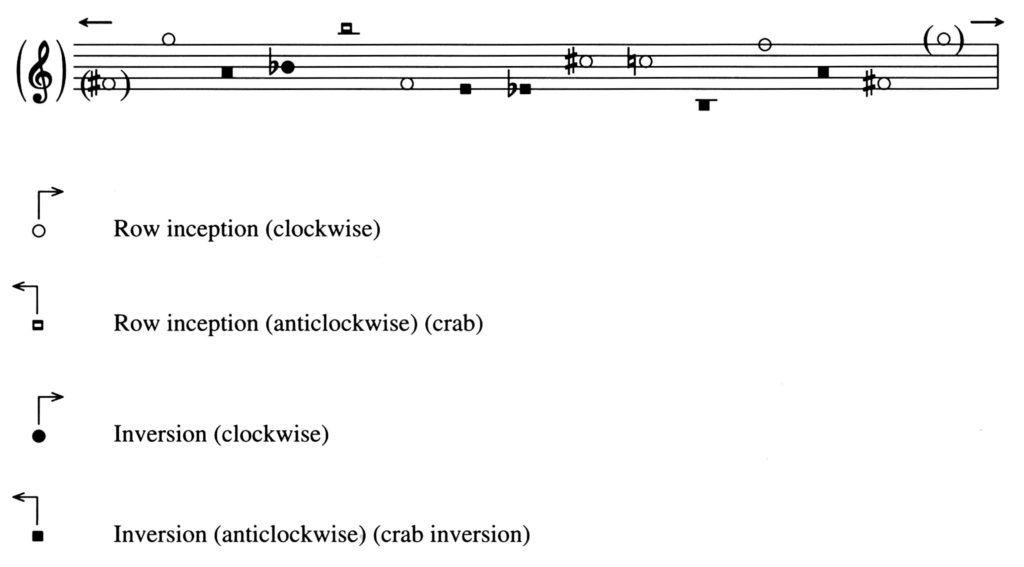

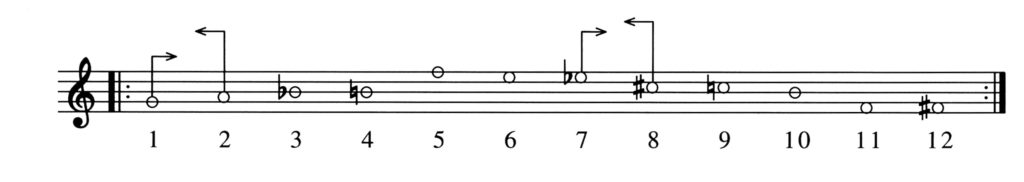

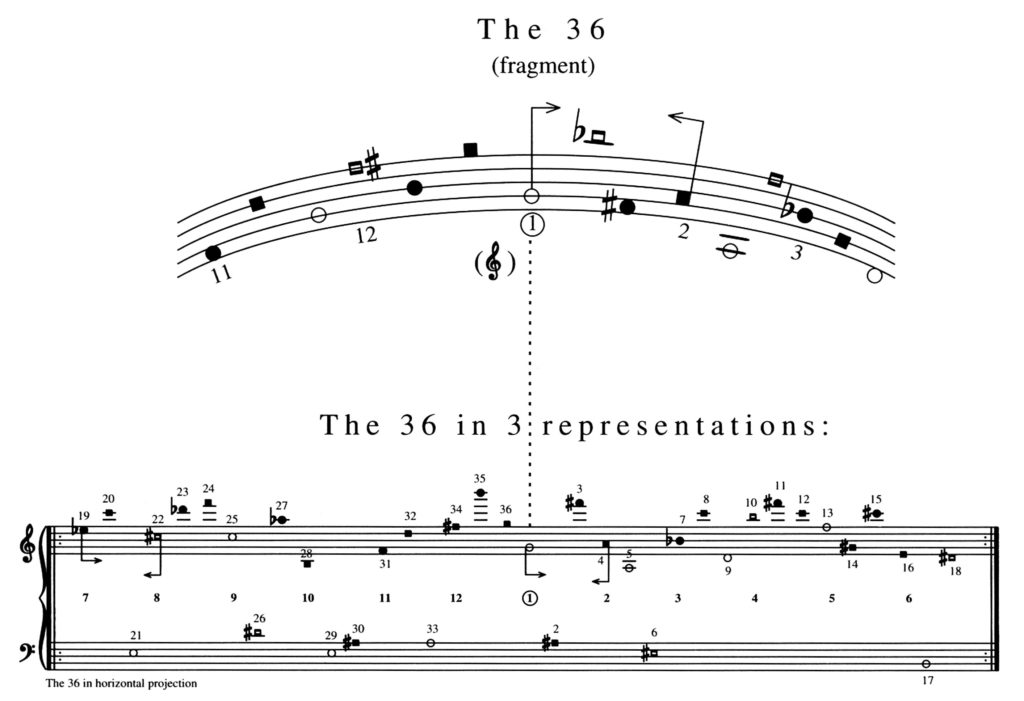

The method of construction is not readily perceived from the actual appearance of a ‘tone lake.’ The following examples (8-13, with accompanying captions) illustrate steps in the construction of the smallest ‘tone lake’, called ‘the 12’. Four segments of the infinity row (Example 8) demonstrate the four well known principles of row-variations: row, inversion, retrograde inversion, and retrograde (or crab). These are of course classical operations, but with new consequences, for the retrograde (and its inversion) will in the course of generating a ‘tone pool’ continue going ‘backwards’ at the same time as the row (and its inversion) continue forward. The paradox is that the segments of rows, which are moving away from each other in two different directions, as a consequence of this procedure not only interconnect but actually never loose their connection. As illustrated in Example 9, the explanation for this phenomenon is that the movements are circular and the projections of the row are ‘forced’ to continually meet and ‘embrace’ each other as they are woven together. Examples 10-11 show the notation of ‘the 12’.

T h e 1 2

Circular representation seems to be the only feasible way of illustrating the directions of the series:

Strictly speaking, the extent of larger ‘tone lakes’ never exceeds that of the original ‘12’. Example 12 shows how the extension of the infinity row actually occurs ‘between’ the original twelve tones which therefore are (re-)constructed in the ‘tone lakes’ in the guise of slower derivations of the added, faster, projections of the row. Example 12 shows the expansion of ‘the 12’ to ‘the 36’ in which process the initial tone of, for instance, the first group of three tones (I in Example 8) is followed, not by a seventh going upwards (as in ‘the 12’), but downwards. (The original tone and the seventh above will recur in the next projection, in accordance with the inversion principle of the infinity row.)

No matter how many tones are in a ‘tone pool’ its basis remains ‘the 12’, but there is a potentially infinite sequence of tones in between each pair of tones. In these bottom-less (oceanic) lakes the composer goes fishing with increasing fascination.

1. Jørgen Mortensen, Per Nørgård’s Tonesøer (Med efterord ved Per Nørgård). Vestjysk Musikkonservatorium 1992.

2. See Mortensen, op. cit. Though written in Danish, this book is generally useful as a handbook with tables of melodies derived from tone pools.

The article was published in: The Music of Per Nørgård. Fourteen Interpretative Essays. Edited by Anders Beyer. Scolar Press, Ashgate Publishing, London, Vermont 1996.