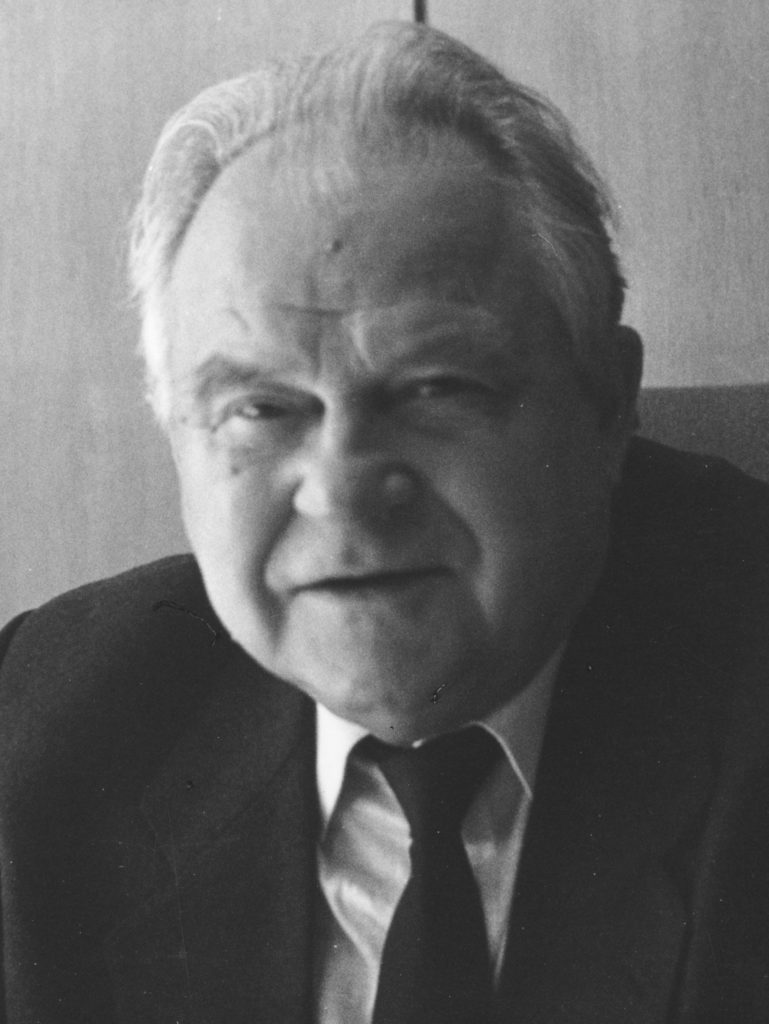

Interview with Russian composer Tikhon Khrennikov

By Anders Beyer

Considering the general state of affairs in Russia, Tikhon Khrennikov, formerly the influential General Secretary of the Soviet Composers Union (SK), is doing well. From his apartment in Moscow he has a view of the monumental building that houses the Department of Foreign Affairs. Under Stalin’s orders a copy of the building was erected in Warsaw (the Cultural Palace). Not exactly an architectural gem, this is one of the many reminders of the past that most Moscovites would like to see demolished. As far as they are concerned Tikhon Khrennikov belongs to an era that is a closed chapter.

Amongst his fellow composers, Khrennikov is judged to have been ‘a man of the system’. They follow this up with evaluations of his character that cannot be quoted here. In the conservatory where he still teaches, portraits of masters such as Shbalin and Shostakovich hang in the classroom. The proud photo of Khrennikov has been removed. The gap in this ‘hall of fame’ is a daily reminder that he has become persona non grata in his lifetime.

As I walk into Khrennikov’s apartment I encounter that part of his long life in music; it remains like a kind of showcase. Press photos decorate the walls and bookcases: the handshake with Ronald Reagan; socializing with Igor Stravinsky. There is certainly plenty to show, and perhaps equally much to hide. For a number of years Khrennikov has been working on an autobiography that will come out later this year. It will, according to the author, document the fact that all the accusations against him are pure piggishness and false propaganda, including Solomon Volkov’s book on Shostakovich which is mentioned in the following interview.

Anders Beyer: Would you tell me a little about your background?

Tikhon Khrennikov: This book here, written in English, is a biography of me. It was published in the USA.

AB: (The interviewer leafs through the book.) From this biography it seems that you have travelled an incredible amount. You seem to have had no problem in getting permission to travel abroad?

TK: All problems evaporated with Stalin’s death. The iron curtain existed under him and it was very hard to make foreign contacts. At that time we knew very little about our Western colleagues and their music. We were cut off from the world.

AB: You didn’t get out of the Soviet Union during the Stalinist period?

TK: No. Nobody did. It was only after Stalin’s death that composers from the West started coming to visit us. After that time friendly connections between colleagues both in the East and in the West began to develop. A delegation of Soviet composers travelled to America for the first time in 1959. Among them were Kabalevsky and Shostakovich. We were pleased that, after a while, the contact was broadened to include not only friendships between musicians, but also friendships between people. The situation in the 1950s had a negative influence on our musical culture. Some musical works and news from abroad did reach us, but only to a very limited degree.

AB: Did you receive privileges because of your central post in the Composers’ Union? I am thinking of the periods both under and after Stalin.

TK: I was General Secretary for five years under Stalin. But I had nothing like a privileged position in the Soviet Composers’ Union, though I had an unbelievable amount of work. Naturally, there was less work when our network of contacts was smaller. Increasingly the work with foreign contacts became very important. We developed both official and personal friendships with leading foreign composers in France, America and Italy. It was fantastic for us. Our lives became normal. Under Stalin one was persecuted if one set up those kinds of relationships. Everything from abroad was cut off.

AB: It must have required great diplomacy to remain on a good footing with Stalin and at the same time to respond to the concerns of the members of the Composers’ Union. How did you tackle the diplomatic aspect of your job? Were you a kind of liaison point between what the regime wanted and what composers wrote?

TK: Composers were completely immersed in the atmosphere that dominated our country. There were no special connections between composers and the government. They lived as ordinary Soviet citizens. The government used Stalin Prizes to encourage composers. Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Khachaturian received Stalin Prizes in 1949 and 1950. I was Chairman for the commission that gave out the Stalin prizes to musicians.

AB: As a member of the committee did you ask composers to write in the same spirit that motivated the prize?

TK: No, everyone composed as they wished. There were certain trends but nowhere was there a recipe for how one should compose. It sounds downright vulgar today when people say that the party prescribed what should be written. That’s ridiculous. I was leader of the Composers’ Union, but I never composed a work that praised Stalin or members of the government. Khachaturian and Prokofiev did. Even though I was head of the Composers’ Union, I had time to do a lot of composing—many songs—all genres of music. I didn’t compose one piece, not a single song, that was dedicated to our leader. There was no pressure at all. Shostakovich composed the song about the woods in 1950, Prokofiev composed a cantata in honour of Stalin, and Khachaturian worked together with Stalin and Voroshilov on a national anthem.

AB: Have historians been fair to you and your achievements? You yourself say that there has been a vulgar distortion of what happened, and that the facts are becoming confused.

TK: I feel it is unfair, but I think it will pass. Currently the predominant attitude goes against me. The avantgarde complains that its works were forbidden, but nothing at all was forbidden. Bans were not a factor for composers. Support for art is based on a love of art. When our avant-garde complained, it was because it was a small clique. They didn’t find support from broader musical circles, nor from our great composers. No-one censored them, they were simply performed less than other composers. Today there is complete freedom and their music could be played anywhere, but where is it? It was a small sect and it continues with its sectarian existence.

AB: Russian composers are not often performed in the West. Is that what you are saying? But there has hardly been a festival in the West without performances of Schnittke or Gubaidulina!

TK: They have become martyrs.

AB: Perhaps you don’t consider them very great artists?

TK: They are talented, but their martyrdom was created on the strength of the current trends. We have more talented composers. Schnittke and Gubaidulina are in vogue. They are not poor composers, but the attention given to them has been exaggerated. It will fall by the wayside like so much else. Only the truly great remain in the end. In our culture there is more than enough that is great and valuable—it is the foundation of the respect our culture enjoys. I speak of Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Khachaturian, Karaev, Sviridov and others. There are many great composers like them.

AB: You don’t think then that Gubaidulina’s success will endure? Are there other talented names that should also be known in the West?

TK: I don’t want to predict anything (laughs). It is fashionable and trendy. Among living composers, I would name Sviridov, Shchedrin, Eshpai, (Boris) Tchaikovsky. But they have been pushed into the background by current trends. There are works by Schnittke and Gubaidulina that I regard highly, but that’s no reason to pronounce them the leaders of our musical culture.

AB: Who has inherited Shostakovich’s legacy?

TK: There are many talented young composers among my students at the conservatory. You’ll have a chance to listen to some of my students, for example, Valodiya Dubinin. At the moment he is at loggerheads with the conservatory because he has neglected to take some courses in which he has to be examined. I would also suggest Serosha Golubkov. They are both wonderful pianists. They’re able to present their ‘wares’ themselves. They are the youngest ones. Among my older students who have now graduated, I would name Alexander Tchaikovsky, forty-two years old. He is one of the most talented from that generation. There are so many who are talented because we have a long tradition of fine musicians. They are not only talented, but also very highly trained professionals. I look with great optimism to the future even though many musicians are leaving us. We are enjoying the growth of wonderfully well-educated practising artists. Even at the ages of fifteen and sixteen they play fantastically well. I have just had a composition recital of my own orchestral works in the conservatory’s large auditorium. A sixteen-year-old cellist played my Cello Concerto. His name is Borislav Strulov, a colossally-gifted cellist. He has just performed in a festival in France and was a great sensation. My Second Piano Concerto was performed by a fourteen-year-old girl, Natasha Zagalaskaya.

AB: I would like to go back to something that we were talking about before, namely the problems before and after Stalin. It sounds as though all problems were eased after Stalin’s death? Would I be right in assuming that some problems did in fact persist after his death?

TK: Not all problems were resolved with Stalin’s death, but the most difficult ones were. Party rule continued and ceased only four years ago. Even under Gorbachev the party leadership continued. It got better when all the interference that had nothing at all to do with music disappeared. A new irritation is that our current government completely lacks any interest in the arts. So I hardly know what is best: concerned influence or this complete indifference and ‘go to hell’ mentality.

AB: Am I right in thinking that you believed in communism as an ideology? Are you still a communist at heart?

TK: Socialist (the Russian translator didn’t dare use the word communist, ed.) ideology has had no real effect in our country. Socialist ideology is a noble cause, but the corrupt forms that it took in our country, served no purpose whatsoever. Under Stalin it took on gangster-like proportions. What matters are the forms it takes and how ideology matches the reality of everyday life. For us it took on crazy forms. Goodness! Save us from turning back to that. We could continue to discuss the problems facing music for days. I am glad to have met you.

AB: One last question. When you have been as highly placed in the system as you have, one must be prepared for criticism. There are also people who have tried to represent you as a villain—as in Volkov’s book, for example.

TK: Everything there is a lie. That book has no connection with Shostakovich. It is a lie for the sake of sensation and money. Nasty. Horrid. Loathsome. I have also written a memoir, it is coming out in the spring, in March or April. It is 300 pages long and contains some sensational things. It is largely based on conversations and reports. Everything is supported with documents. It is actually the history of Soviet music in this period. I’m publishing quite a few secret documents from the Central Committee on the affair in 1948, among other things. I describe my meetings with Stalin. They were very interesting.

AB: How did you obtain these papers?

TK: I was helped by the editor, Mrs Robtjova, who is head of the Composers’ publishing house. She was able to gain admittance for me to the archive that holds the documents I am publishing. I write about Shostakovich and Prokofiev exactly as it was because I was around them almost every day at that time. I also write about Stravinsky with whom I became a close friend towards the end of his life. I have had some very interesting experiences, as well as some that were difficult. The book is of particular interest to musicians. An American advised me to write a popular book. I dictated my thoughts to him for ten days, six hours a day. My book will surely be of great interest to you. I don’t know if it will appear in English.

I am currently imposing some order on my own huge archive. I have found a letter from Shostakovich. On 30 October 1948 he wrote,

Dear Tikhon Nikolajevich, I send you my hymn for choir, orchestra and two pianos. I have revised the ending according to your suggestion about the ending of the melody at rehearsal letter 2. Your advice centered on the idea that I shouldn’t repeat a turn that had appeared already two bars earlier. It doesn’t work to repeat something so soon. Greetings, Dmitri Dmitrijevich. P.S. I am worried that the orchestra and two pianos will sound bad. Typically, the piano sounds physically weak with a choir.

This friendship continued until Shostakovich’s death. When Volkov and others want to represent themselves as being close to him, they come up with all kinds of lies about me because I was at the head of Soviet music. My character is such that I don’t let lies affect me. Life will set everything straight. I have a completely clear conscience with respect to all my colleagues.

© Anders Beyer 2000.

The interview was published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000. The interview was also published in Danish, ‘Jeg har ren samvittighed: Et interview med Tikhon Khrennikov’, in Danish Music Review, vol. 67, no. 5 (1992-93): page 151-154

Biography

Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) first studied composition in the Gnessin Institute in Moscow, but later transferred to the Moscow Conservatory where he worked with Vissarion Shebalin. From 1941 to 1955 he was Director of Music at the Soviet Army’s Central Theatre, and from 1948 to 1991 he was the First Secretary of the USSR’s Composers’ Society. In his various roles (for instance, as a member of the Control Commission of the Central Committee), he was an important link between the political establishment and his artistic colleagues. Khrennikov’s scores are published by the Internationale Musikverlage Hans Sikorski and recordings can be found on Russian Disc.