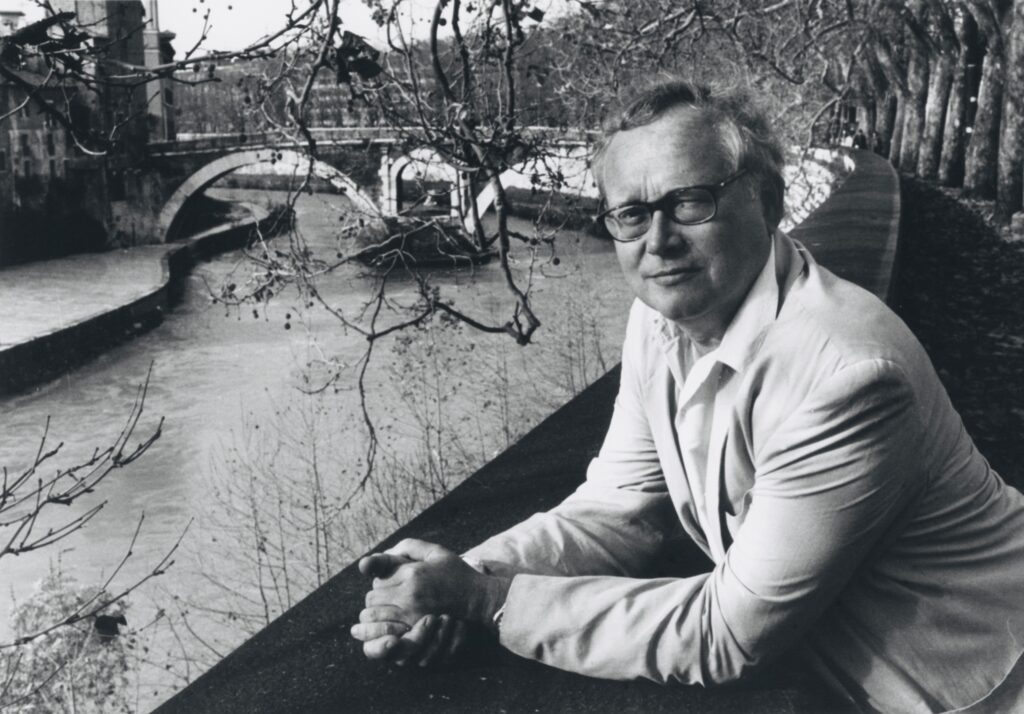

Interview with Danish composer Karl Aage Rasmussen

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: ‘To see is a matter of selection, memory and interest. And using your eyes, of course. But he who sees the best, doesn’t always see the most’.

Thus writes the short-sighted composer, Karl Aage Rasmussen, in the entry on ‘Sight’ in Brøndum’s Encyclopedia. Vision depends on the eye that sees and even a person with impaired vision can see a great deal, possibly more than others. Seeing is a matter of perception, viewing is merely registration.

So, here we have a near-sighted artist writing about sight. Things are not what they seem to be—everything is turned upside-down. Karl Aage Rasmussen you have always been interested in things, thoughts and phenomena that could be turned upside-down. When did you first see that you would be a creative artist?

Karl Aage Rasmussen: I didn’t see it at all. It is lost in utter darkness. After all it’s not a decision you make, certainly not when you start as young as I did. My first scribbles and my first attempts to compose something go back to when I was seven or eight years old.

My parents were what we call ‘workers’ nowadays. My mother was a needlework teacher and my father was a typesetter. Rather by accident we got a piano and my mother insisted that I take lessons if it was going to take up space in the living room. I remember that very early on—God only knows why—I tried to write music down. And that was strange because there was precious little tradition of art and certainly no musical tradition in my family.

I hated piano lessons and stopped hating them only when my indefatigable mother discovered Edmund Hansen—a colourful man nicknamed ‘Toscanini’ and given to drink. He directed the local semi-professional City Orchestra which gave performances only a couple of times every year. He had been trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Music though, and he taught violin and piano. When I lamented my ignorance, he also gave me lessons in orchestration. So at twelve or thirteen years of age I actually worked on orchestration exercises.

Perhaps you imagine that I was immersed in Stockhausen, Ligeti and so on, but I didn’t know the music of the avant-garde at all. Actually, in my youth I believed that all composers were dead. Svend S. Schultz was a revelation to me. I devoured Svend Erik Tarp’s sonatinas and at secondary school I arranged several concerts at which I played—or whatever you want to call it—things like Niels Viggo Bentzon’s Træsnit (Woodcuts), much to the amazement of my classmates.

Most of us experience a similar development. We start in a corner with something we like and end up in an entirely different corner. I still remember hearing Carl Nielsen’s Violin Concerto when I was thirteen years old. To me the introduction to the first movement seemed utterly meaningless and incomprehensible, something which was of course reflected in the music I composed myself. My first compositions, written when I was ten, were endless variations on the first movement of the ‘Moonlight Sonata’. Then there was a heroic ballade about King Agner for which I wrote both music and a text stuffed with alliteration and old Norse poetic devices. Later came a period where my so-called compositions were mostly modelled on a few bars of Hindemith. When did I become a composer? When I left secondary school before passing my last exam in order to enter the Music Academy, I suppose I must have felt something pointing in that direction.

AB: Tage Nielsen, who was Director of The Royal Academy of Music, Aarhus, at the time you were a composition student, told me that you were also a good violinist. And I have read that as a fifteen-year-old you played Grieg’s Piano Concerto in Norway. That practical grasp of things, that is, the ability to both perform and compose, must have been an important aspect of your development.

KAR: It’s been neither important nor unimportant. It’s just the way it has been. Two sides of the same thing. Playing led to thinking about compositional procedures and that led to writing something down. At times musical thoughts had to be performed in order to be clarified as thoughts. I could never be a composer who composes at his desk.

I remember Emil Telmányi (the Hungarian violinist who became Carl Nielsen’s son-in-law, ed.), a unique individual who was my violin teacher, with great respect. Frankly you could learn more about music in one hour with him than in a month studying so-called music theory, and I think that experience made a lasting impression on me: music without a corporeal aspect, music not involving musicians is, essentially, not of interest to me.

AB: Tage Nielsen, whom I mentioned above, also said that you were actually good at almost everything, that you wanted to excel in everything and hated getting wrong anything in which you were involved. You also made no secret of the fact that you wanted to be knowledgeable in a number of areas. You have done a lot of debating and writing over the years, and often with weight and a conciseness that doesn’t exactly invite contradiction. If one slurs ‘Karl Aage’ (Rasmussen’s first names by which he is known, ed.) together, it sounds like ‘Kloge’ (meaning ‘a clever guy’ in Danish, trans.). You don’t show uncertainty in public, but I assume that as an artist you are always insecure. Somewhere you have written that your opinions are calculated more to invite discussion than to seek acceptance. What has it been like throughout the years to have to live up to the role of an omniscient author, sharp debater and a virtuoso in verbal fencing? I ask because it has been difficult for me to find what’s at the heart of Karl Aage Rasmussen, the man. Not that I want to intrude on his private life, not at all. But I have the feeling that sometimes he could be hiding behind words, perhaps also behind music.

KAR: You raise a cloud of issues there, but let’s begin with the picture you draw of a public person whom I hardly recognize. I feel a bit like Chaplin in the film where he plays a mass-murderer. Every time the judge reads a new charge Chaplin looks over his shoulder in order to see just who this defendant is. Can you be self-assured and resist opposition, and at the same time invite discussion?

I have a reputation for being fond of discussion. It may be that I think best when I am conversing. It’s not that my head is empty when I am on my own, but there is not nearly as much going on of that which we usually call thinking. However, if you imply that, for instance, my writing has focused on pegging out directions or passing judgments, then you must be talking about someone else. Most of my writings offer personal ideas about music and musicians, about things that interest me. I presume that the personality emerges in the selection, in the writing, in the style.

Currently my publisher Gyldendal is preparing a collection of my essays for publication, so I have recently read and re-read lots of Rasmussen without finding much verbal fencing. Perhaps there is a bit of mythology here: when people begin referring to someone as ‘clever’, the myth becomes self-fulfilling. Besides there is a psychological aspect involved. Of course I know what insecurity is. I am actually rather inward-directed, so discussions and conversations may act as defence mechanisms. As may humour, for that matter.

The image of me as a kind of ‘musical executioner’ or whatever seems to me completely distorted. I haven’t been heavily involved in public debate, for one thing. Once in a great while—like a miniature Holger Danske (the legendary Danish king who wakes up from his perpetual slumber only when the country desperately needs him, ed.)—I have been involved in polemics, but God knows, I have never been addicted to debating like, say, Niels Viggo Bentzon. I have no wish to be remembered as a mass producer of opinions. I have always wanted to contribute to new agendas, however. Possibly this also has something to do with my being and remaining a Jutlander, instinctively opposing the idea of Copenhagen as a ‘centre’. We have a long tradition for challenging the cultural balance between the province and the capital city.

AB: In a conversation with Stockhausen during his visit to Copenhagen in 1996 you asked him about believing in something. In 1982 you also asked Nørgård and Gudmundsen-Holmgreen about their belief ‘in a wider context, in a guiding power’. Now I’m going to put the same question to you: What do you believe in?

KAR: To answer that question you must choose a specific angle. I don’t have any religion in the more involved sense of the term. My belief is that it’s worth searching for a belief, taking the old view that what matters is not the goal, but the road to it. Like happiness. It’s not a final destination, happiness is what you experience on the way. If faith means arriving somewhere where everything is tranquil and harmonious, and where you know how it all fits together, then I don’t know what faith is.

I am more inclined to establish a temporary belief. For example, an artist has to believe that what he is doing is meaningful. A composer makes hundreds of choices every single minute. This presupposes a belief that every choice is the right one at that moment. Belief in that sense may come closer to a word like attitude. When I feel a solidarity with composers whose music barely resembles my own, it is because I am influenced by their attitude. For example I have often been fascinated by John Cage. And everyone who has been involved with Cage knows how his opinions may develop into something that looks a lot like faith—because you believe that it can be fruitful to behave the way Cage suggests—that in freeing yourself from your likes and dislikes you will be more aware of what is actually happening here and now. I have often recommended—to myself and to others—that one should be less deeply involved with the past and a little less fixated on the future so that there is room for the present.

AB: To be inclined towards something means that you wonder about things, something you have in common with John Cage. Among the many composers to whom you have paid close attention, Cage is probably the one who in all his activities has influenced you the most. Correct me if I am mistaken.

KAR: It is somewhat characteristic that there are many composers who have ‘influenced me the most’. For example, I came to Cage via Charles Ives. My relationship with Ives has become paradoxical: how can the most important composer in your life be one whose music you never hear? I hardly ever listen to Ives’ music, but nevertheless, it is an ever-present impulse. That seems to indicate that there are aspects of the very nature of music which, for want of a better term and in a particular sense, may be called ‘spiritual’—something which is absolutely central for me.

AB: You once wrote: ‘Even if John Cage’s music should be forgotten one day, his mind models will remain among the most influential of the century’. I understand that rather than his music, it’s more his attitude, his way of viewing the world that inspires you.

KAR: There is a concept in that quote which is not mine, but one that I may have introduced in our latitudes, the anthropological term ‘mind model’. Apparently our brain tends to work on the basis of habitual mental circuits. It is impossible to think about everything all at once and so we devise methods of fixing specific ideas in our mind, fitting them together in habitual ‘models’.

For example, we have music on one side and notation on the other. Initially notation was used only to help us remember music, but at some point it turned over and began influencing the way in which we think about music. We began thinking about music as something which is notated before it actually sounds. This entirely changes our conception of music. I am disinclined to use moderate words like attitude, but would rather take a broader view. Let’s just call it our concept about music, our ideas about what music is by and large.

Let me recall one of my favorite stories. Ives’ father, George, was a bandmaster in a little provincial town in Connecticut. Ives writes in his essays about a young man whose ‘musicality was limited after three years of intense study at Boston University’. He heard George Ives’ church choir in which there was a certain Mr. Bell, who was bawling ridiculously out-of-tune. ‘You can’t have Mr. Bell in the choir, he ruins everything’, said the nice young man from Boston. George Ives answered, ‘Well, but look at his face when he sings. Don’t pay too much attention to the sounds, or you may miss the music. You won’t get a wild, heroic ride to heaven on some pretty little sounds!’ That story is a mind-opener for me, and it relates closely to something that Ives said himself, something which sums up the entire matter: ‘My God, what has sound to do with music? What it sounds like may not be what it is’.

This is crucial but difficult to explain because it concerns the transcendental in Ives, that which transgresses boundaries, the simple fact that music is so much more than something we listen to. It is the present absence of this awareness that has led me to say that we live in an unmusical world submerged in music. Because as a spiritual and mental phenomenon music can be so infinitely more than that which sounds. It lies at the core of my way of thinking and from there it spreads in all possible directions. It has also helped open my ears to all those who have been overlooked and not heard. It isn’t enough for me that music is aesthetically satisfying, for instance, or artistically, or stylistically successful. I search for something behind music, so to speak.

AB: Can this ‘other’ that is behind be articulated? Or is it that ‘It can only be referred to negatively, as something absent’, like the German philosopher Adorno said?

KAR: Here I’ll take comfort in the old church father, St Augustine, and paraphrase his comment on time: ‘When no one asks me, I know what it is, but if someone asks me, I don’t know’. For Ives, it meant the concept of ‘strength’, of course, the power to transcend boundaries. Valuable music is music which has the power to break down barriers in our heads. Inconsequential music just sounds pretty, and is, in Ives’ words, ‘an easy-chair for the ears’.

AB: The strength to break down barriers. Give me some examples of music of our time that you feel has this power to break down boundaries.

KAR: That is very personal because you are seeking something that can break down boundaries in your own head and make you react in an unexpected way. Cage says somewhere that if you rub people the right way, they say ‘Ahhh’ and if you rub them the wrong way, they say ‘Ugh’. It’s an incredibly predictable pattern of response, a cultural situation that risks making us into Pavlovian dogs who salivate and bark on artistic command. My own ‘transcendental’ experiences are rather easily determined by looking at, for example, the list of composers I have written about, talked about, programmed in concerts, etc.

But not to sidestep the question, let me mention a unique individual who might epitomize all those odd, ignored, eccentric individuals. The music of the Italian composer Niccoló Castiglioni is impossible to describe, but that’s precisely the reason I find it significant. And that might be a rule of thumb: if the music can be described precisely in words so that you can just about hear it in your mind, then it doesn’t contain what I am looking for. In order to have any idea about what Castiglioni’s music is, you have to hear it, Inverno in-ver, for example. And somewhat the same is true for Luigi Nono or Giacinto Scelsi, speaking of Italians.

AB: Nevertheless, I remember that you tried to describe these things in an essay that you wrote about Castiglioni when he was the featured composer at the Lerchenborg Music Days. Talking about this seems just as impossible as it was for the art historian who, when he lectured on the sublime, pointed to a place in a painting and said, ‘Here we see the sublime’. Whereupon a member of the audience said, ‘Where? I can’t see it’. The attempt is just as interesting as it is impossible. And yet we continue to try. So I have to ask you again, aren’t you always trying to create the sublime and break down all the barriers?

KAR: There is no particular strategy or method that will enable music to transcend borders. That has been a guideline in my life-long show-down with strategies, systems and methods. It is very difficult for a modern composer to write music without the support of some kind of methodical thinking. And it is not only hard for the modern composer, but for any composer because all music is related to conceptual models. Of necessity the notes must follow each other in sequence because time passes, and if we can’t make it meaningful somehow for one note to follow another, then sooner or later we find ourselves in a vacuum. So we search for strategies.

But transcendence will occur only when methods or systems collide with the unpredictable, when they bump into something incalculable. This happens, for example, in the case of Ligeti who is an extraordinarily methodical, systematic composer. But in an archetypical, profoundly moving way, his methods are pierced by something unforeseeable that creates a universal psychological dimension. That’s the source of power in his music.

The Polish writer Gombrovitch claimed that modern music is corrupted by mathematics. But is it really any more ‘mathematical’ than, for instance, Bach’s music? Bach isn’t different from Ligeti; both count and count, but suddenly all the numbers disappear in the experience of a spiritual or downright physical response to the music itself.

The peaks in my own experience of listening to music are when these boundary-breaking moments occur. Music is mathematics, tones are measured frequencies, and just about everything we calculate or work with in music depends on numbers. There is a wonderfully thought-provoking line by Leibnitz, the German philosopher. He writes that music is a mathematical exercise for the soul, but the soul doesn’t realize that it’s counting. And who dares to suggest that he knows what the soul can hear or how it counts?

Long ago I abandoned my youthful and overly sensitive skepticism about numbers. They have come to play an increasingly large role in my music in the last ten or fifteen years. Again this was rooted in my personal history, for given my temperament as you described earlier, that is, a kind of habitual anti-feeling, it was clear to me that if there was one thing I would not do, it was to go along with Central European modernism, which was at that time a cloud of numbers.

AB: You said before that one note must follow another because time passes. We will return to that in a minute. So far you have described what it was that you didn’t concern yourself with at first.

One of the first writers who commented on your music was Jørgen I. Jensen. In the article in Dansk Musik Tidsskrift, ‘Nye, aldrig før hørte sammenhænge’ (‘New connections, never heard before’) from 1969 he wrote about two orchestral works, Repriser, fristelser og eventyr (Recapitulations, Temptations and Fairytales) from 1968, and Symfoni for unge elskende (Symphony for Young Lovers) from 1967. He describes the music as a ‘musical kleptomania that goes beyond anything anyone has seen before’. Can you look back at your earliest days as a composer and tell us how that stylistic individuality developed.

KAR: Once in the 1960s I heard—in a lecture dealing with something completely different—about a wild man from the prairies who composed music with quotes from all possible sources. I immediately tuned in to Ives, because I had always been interested in working with material that already existed. In French aesthetics it is known as objets trouvés, that is, you find existing things and put them together. It meant a lot to me to be invited to the centennial conference on Ives in New York (1974) where I met composers such as Lou Harrison, Elliott Carter, the pianist John Kirkpatrick and many others who had known Ives for 25–30 years.

To this day it would never occur to me to think of myself as an expert on Ives. I have been interested in Ives for personal reasons, not as an object of study. I have taken what was important and thought-provoking for me and that’s what I have written about, and used in radio programmes, performances, and so on. The most important thing for me at that time was the discovery of a composer who took what he needed, without any scruples. He was exposing the expressive power in all kinds of musical material—without asking whether it was something he or someone else had originated.

It was nothing polemical. It wasn’t directed against the great Western European Erfindungskultur, the old notion of having to be original, of using material that must be nie erhört—previously never heard (in Stockhausen’s famous words). It was just natural for me to work in that way. That is how I started out as a young boy. And remember also that this was the time when Mahler’s music suddenly became fashionable.

The title of Jørgen I. Jensen’s article was of course aimed polemically at Stockhausen’s ‘previously never-heard sounds’. It emphasized the fact that I wasn’t a composer who said, ‘I can’t invent anything myself, so I snatch what I need from somebody else’, but that it was simply a way of doing something totally different.

AB: Now, you mention Mahler, who composed a song that he used again in a symphony, that Luciano Berio used, and that you re-used in your work, Berio Mask. Why do you think that a certain expressivity, which was valid in Mahler’s time, must now be understood, in some sense, as being used up? A recurring defence of recycled music is that in new surroundings it may carry a new expression, as it were. Let’s revisit that piece where you work with the recycling of material that has itself been recycled twice. You call it a ‘palimpsest’. . .

KAR: To explain that, we have to go back a number of years. In the beginning of the 1970s I composed pieces that might still be interesting simply because they are so odd. The prototype perhaps is Genklang (Echo or Resonance), for piano four-hands, prepared piano, out-of-tune piano (that is, a honky-tonk piano), and celeste. In short, it captured a gradual distortion of the refined sound of the grand piano, a kind of time perspective where a sound is stretched out in an echoing space, or in a hall of mirrors if you like.

Genklang is characteristic of what I was doing at that time because it consists of an infinite series of tiny musical modules. I tried to figure out just exactly how few notes were necessary to be able to identify a particular musical style, for example, a Rheinland polka. Sometimes I felt that just four semi-quavers were enough. And that became a tiny patch that I could sew to another patch taken from completely different music. But since that was also reduced to a very few notes the whole didn’t seem like a ridiculously fast film with cuts from thousands of films. On the contrary, the very tight editing technique made it possible to hear something similar to directional cohesion.

Also it had something to do with thinking about music, something to do with Ives, something to do with everything but sound itself. It also had philosophical overtones. Having just read Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus I imagined trying to do what his unfortunate main character, the composer Leverkühn wanted to do—albeit aware of the tragic costs that he had to pay—namely, to actually create a ‘new’ musical language. I thought that was a fantastically interesting idea: a new musical language that consisted exclusively of old ones.

But I quickly realized that my great vision was doomed to failure. There were problems of form and development that seemed insoluble. We hear an immensely tight montage, but how on earth does one phrase lead on to another in such a montage? How do you establish a beginning and an end? I finally decided to compose a work embracing this problem even in its title.

Writing a big piece on the impossibility of writing a big piece suited the spirit of the times. The work was called Anfang und Ende (Beginning and End), the story of a beginning and an end that can’t be. It became a farewell to the hope for a new meta-language, and I began to search for other means to accomplish something similar. Since the problem was one of form it was clear that the next step had to go beyond recycling tiny modules by ‘recycling’ a larger formal shape.

This attempt was already partly evident in Genklang in so far as a famous slow movement by Mahler is actually hidden in the formal framework of the piece. In the piece called Berio Mask there is, to an even greater degree, a pre-existing form: a movement by Mahler that he himself had developed further and that Berio had re-composed.

It was a kind of conversation between the different historic layers. This is something that has never ceased to fascinate me: the history of history, the history of what it is we mean when we say ‘history’, that is, history as a phenomenon in time, as a manifestation of different times, as something that also expresses itself in the form of different tempi. The composer Hans Gefors compared Anfang und Ende with the Italian painter Arcimboldo who painted faces out of fruits or vegetables. It looks like a face, but in reality it is an assemblage of fruit. My work looks like a symphony, but it really is nothing but tiny quotations.

AB: I have had several opportunities to listen to Genklang. The work is a perfect example of historical perspective. Let’s go deeper into the work. The sound of the piano is like — if you’ll excuse the continuing use of the fruit metaphor — a fallen fruit, or rather, a really rotten piece of fruit. You use an out-of-tune piano and distort the ideal sound that other composers have previously used very successfully. What composer’s sound did you have in mind?

KAR: The out-of-tune piano mainly represents Mahler’s music: the Adagietto from his Fifth Symphony was in vogue at that time as the theme music of Visconti’s screen version of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. Here it represents a myth of cultural decay. The idea of this music as a huge romantic gesture and, at the same time, as cultural refuse, prompted me to fit it into an ironic, but also a clearly fermenting, crumbling context. The out-of-tune piano refers to decadence but at the same time to yellowed album-leaves of music—the Viennese waltz, small barcaroles, salon music and so on. It is like a truly romantic world that turns into a sunken cultural treasure as you listen.

I loved and still love this Adagietto, but obviously I couldn’t use it at face-value because of the romantic Schwung. Exposed to the out-of-tune piano it loses its persuasive romanticism. However, it still possesses a stirring, universal and human profundity because romanticism isn’t confined to a past epoch. The ‘romantic’ experience is a discovery containing universal human dimensions.

AB: It has been said that the characteristic aspect of your music from that time is that it is open to expression, that the listener gets to the point where a large cleared field can be surveyed as a whole so that new relationships and patterns appear. That sounds very poetic, but wasn’t that way of composing a way of welcoming a substitute for burned-out serialism rather than a music and a technique that would be fruitful in the long run?

KAR: I think that I have answered that. There was an element of rebellion in it, but it wasn’t a terribly informed revolt because I didn’t know very much about Central European serialism. It is senseless to stage me as somebody representing a confrontation with serialism. The fact is that I simply discovered my own voice as a composer.

AB: I ask because you said that you knew in any case what it should not be. Having said that it shouldn’t be European modernism, then in a certain sense it must also have been a reaction against something at the same time that it was a deep fascination with Ives?

KAR: I believe that a lot of art arises from a strong feeling of what something should

not be rather than from a clear idea of what something should be. Take for example the film Vinterbillede (Winter Picture) where the great Danish painter Per Kirkeby paints his biggest canvas ever. It is a film about how artistic conception sometimes takes place after birth. First the picture is born and then it is conceived. The film is almost scary: the painter paints what looks like a fantastic painting, but he goes on reworking it, changing it, over and over again, and at some point the terrifying artist pours a can of paint over the very best part of the canvas!

He doesn’t just paint a painting that already exists in his mind. He starts by doing something that sets him thinking about what it is he wants to avoid. I once described this pattern of reaction in the Danish composer Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen as ‘the poetry of opposition’, and maybe it is also pertinent to Kirkeby. It certainly also hits the mark with me—the realization that poetry arises when one tries to avoid something, when something seems too much one thing or another, too sentimental, too powerful, expressive, simple, what have you. The friction that comes from trying to avoid something is a better incentive for me than the energy others get from knowing what they want.

AB: During the making of Winter Picture there are stages when you think that it is really beautiful, that the painting could very well be complete. However, the artist doesn’t stop, but goes on because a physical restlessness tells him that something isn’t as it should be. Towards the end of the film, the artist actually becomes ill. He can feel that the painting is now almost as it should be. Is that also true for you? Do you know precisely when a piece is finished?

KAR: One of the most difficult decisions for an artist is to decide when to stop. This is where gut feelings, experience and technical insights are maybe most needed. Morton Feldman told a story about a painter who was always slightly drunk and always spent too long on his pictures. When he went down to get another bottle of whiskey, his colleagues working in the same atelier took the painting off his easel and put up a fresh canvas in its place. When he came back he looked confused for a moment and then began to paint a new picture.

All artists know that a work can be ruined by working on it for too long. The real artist is one who knows when to stop, not necessarily one who has a clear idea in advance of how everything should end. Feldman said that his extremely long pieces just died of old age. I have known that feeling now and then—the work dies because of a kind of psychological debilitation that you yourself experience in your relation to it.

It doesn’t mean that I say, ‘Now it is perfect’, or ‘Now it is finished’. But it means that there is a moment when there isn’t anything more I can offer to the work. Then it is best to begin something else. Composers in earlier times had a number of technical means by which to finish off a piece. We do not have that in the same way. Perhaps the very concept of ‘finished’ doesn’t make the same kind of sense any longer.

AB: There was a period when you worked with a stylistic idea that is now either abandoned or further developed. You worked with collage music, quotations and with analytical studies. At that time you said that ‘the experience of the well-known in a strange context and of the unknown in a familiar one calls forth new meanings and forms and consequently new ways to listen’. But the available musical resources weren’t enough for you to be able to sustain this stylistic basis.

KAR: It can hardly be called a ‘stylistic basis’, but it is correct to say that a new way of listening concurs with my thoughts on sound. If sound is what defines the phenomenology of music then it implies that our ears know how to handle it. And if we are exposed to a sound that our ears don’t know how to handle we have to ask, ‘Is this music’? and, ‘What actually is music’? Therefore attempting to redirect the ears, so to speak, has always interested me, as well as opening our ears to things that otherwise might be screened out by conceptual models. All of us know that we usually listen in a certain way and that consequently there might be something else that we completely ignore.

Someone had the idea of playing Beethoven to pygmies in New Guinea to see how they would react. But they didn’t react at all. After a few minutes of being amazed at the noise over the loudspeakers they tolerated it and acted as if they heard nothing. Perhaps Beethoven for them is what static noise on loudspeakers is for us. That’s what I mean by ‘mind models’. In order to hear anything at all, our ears—and our head—have to be tuned to certain wavelengths. And the structure of our thought will determine what we hear. It seems obvious to me that the broader our mind models, the greater the range of our experiences.

At the end of the 1970s I considered various means by which to handle my ‘non-style’. I was kind of redeemed when I started writing musical drama. I did it for much the same reason that Webern started writing songs—he also had a problem with form. When you have to work with a text, and particularly with a text with a well-defined dramaturgical plan, then you have the formal shape in advance. Just as I had used a pre-existing shape in advance, so to speak, by building music inside a movement by Mahler.

Besides, musical drama makes the stylistic element—still the favourite metaphor in the aesthetic debate—less important. It is self-evident that in music drama the music doesn’t always represent a specific aesthetic stance but is subject to the dramatic situation. Even Schoenberg used quotation-like material in his operas. So here you have something like a neutral position where the importance of style as a means of personal expression is no longer of top priority. A less committed position, you might say. That’s how it worked for me. I wrote two works quite quickly, one right after the other, first the opera Jephta, commissioned by Jutland Opera, and after that, the first in a series of works related to an unorthodox, maybe rather naïve attempt to create a personal alternative to established music theatre institutions, namely, the ‘scenic concert piece’ Majakovski.

AB: Once you asked Per Nørgård and Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen how they felt about their earlier works. To judge by concert programmes, your earlier music no longer arouses a great deal of interest, something that is also true for two composers who worked with related methods, namely, Poul Ruders and Bo Holten. Like yours, their earlier works are not performed very often. You all worked with recycling. Do you have an intimate relationship with your early works or are you skeptical about the works of the young Rasmussen?

KAR: Why should you look skeptically at something you have done with honesty and integrity at an earlier point in your life? Je ne regrette rien as Edith Piaf used to sing—‘I don’t regret anything.’ But the question is whether I still have any relationship with them at all. The question is whether I have any relationship with the work that I finished a month ago. I perceive everything to a very, very high degree, like Kierkegaard says, as stages on life’s path, and therefore, as things to which you really cannot return. When I hear my earlier works, I feel a bit like when I accidentally meet a girl I once knew intimately. I may find it difficult to understand what on earth we once shared. But of course I don’t regret anything, and probably someone else likes her now . . . .

AB: In one place you write, ‘Personally, I have to pinch myself in order to comprehend that I was the same person then as I am now’!

KAR: I believe everyone recognizes that experience, but an artist recognizes it in a particularly intense way. We are confronted most inescapably with our past when we sit in a concert hall and listen to a piece that is twenty years old. I don’t know what to do with it other than feeling a slightly touching recognition that, ‘My goodness, that was once me! Was I really interested in that sort of thing then? Did I really think that was the right way to handle a musical or an artistic problem’? At the same time I have to say, ‘Yes, that’s apparently what I did’. But to do as some do and proof-read one’s earlier work from a later perspective seems pointless and plainly dishonest to me.

AB: Now that we are here talking with ‘grand gestures’ it is tempting to talk about who is dead and what has died. There are those famous quotes like ‘Schoenberg is Dead’ or ‘Is stylistic pluralism dead?’ Almost all of you have abandoned unequivocal references to any given model.

KAR: If I have abandoned anything, it must be multiple references. There are very, very few unequivocal references in my music, because among other things, the so-called quotations that I used were so short and so anonymous that they can rarely be heard as referring to a specific piece of existing music.

AB: But I have frequently used Berio Mask in my seminars and can contradict that, since the listeners were able to hear at least Mahler, if not Luciano Berio.

KAR: True, there are a few—let’s call them—‘exceptions’, but they are exceptions of a special order. The most obvious example is Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Fugue which I de-composed in my work Fugue. There are in fact only three pure examples of decomposition in my output and we have not mentioned the main one, namely, my cello concerto with the title ‘Concerto in G minor for Cello and Orchestra by Georg Matthias Monn freely re-composed by Arnold Schoenberg and further developed in the Style of Stravinsky by . . . me’. It sounds like a joke and so it is, in a way. You may just as well call it my Cello Concerto. As a matter of fact, the piece has a real title, Contrafactum, meaning not just ‘against that which exists’, but Latin for ‘forgery’.

That is probably the work in which the question of authenticity is most urgent, and also the work that has had the most difficult existence. It has only been performed a few times and hardly anyone has shown interest in it afterwards. It is a very special piece, unique for me, because it is the style itself that is being decomposed. It is a complete work by Schoenberg, a reworking of an early classical piece that I took just as Schoenberg left it. But I reworked it the way I imagine Stravinsky might have. The sound of this piece isn’t necessarily all it is about. It is music that challenges concepts like ‘authenticity’, ‘history’ and so on, and sets thoughts in motion in the minds of people who think about such matters. Which, apparently, not very many do.

AB: You have talked about the time around 1970, when your music—on one level—treated the problem of composing. Your Second Symphony which you mentioned earlier, Anfang und Ende, is a good example of that. You referred to Hans Gefors’ interpretation. At one point Gefors wrote, ‘Karl Aage Rasmussen’s music [is] a battle between the will to express itself and the oppression of the cliché. This is part of the realisation that today’s musical language is based on music that once emerged from the vital minds of the composers of our culture but now is reduced to clichés. Such a musical language is in conflict with that of its dead ancestors’. What do you think of this description?

KAR: That it hits the spot. This set of problems played a role in that whole period of my life when I was preoccupied with researching new or over-looked expressive possibilities in pre-existing musical material. According to the classical European avant-garde tradition (Schoenberg, serialism, etc.), that which pre-exists has already become a cliché. From that perspective expressing oneself truly becomes a battle against the weight of clichés, as Gefors says. But it’s not a hopeless battle because there is a means of expression that doesn’t rely on the material as such. The Dane Gudmundsen-Holmgreen has shown, and often with great simplicity, that poetry and expressivity can be found almost anywhere—in a discarded jazz chord or in a cast-off piece of cultural refuse—and be quite independent of where the material originated.

But as mentioned earlier, I gradually moved in other directions even though my interest in the idea of ‘history’ continued to burn. I began to experience the sequence of historical epochs as a metaphor for something that had to do with both time and tempo. And gradually it turned into a more direct interest in the experience of time, and in the mark of time on the artistic material, on the music.

AB: I would like to return to the question of time which has occupied you in your later works. The 1970s interest me, not least because you were one of the first to realize that it is important to discuss the perception of music. That was something to which little attention was being paid.

The article, ‘Oplevelse, analyse og pædagogik’ (‘Perception, Analysis and Teaching’), concerns the ‘biology of the musical experience’. In the introduction you wrote, ‘In the debate concerning music teaching . . . there is not much discussion of “perception”. It is something that is taken for granted’. As is well-known, the problem of perception-orientated pedagogy and musical thinking was readdressed with an abundance of materials later. You write in this article about the wall between the ‘personal’ way of dealing with music as ‘a means of spiritual influence’ and the pedagogical side of dealing with music as ‘a means of consciousness, analysis and teaching’. If I understand it correctly, the main influences on your spritual development have been the works of Ives, Cage, Ligeti, Nørgård.

KAR: Among others.

AB: Are there other composers whom you would like to include in this regard?

KAR: Oh yes indeed, mentioning in no particular order, Stravinsky, Satie, Busoni, Nancarrow, Hauer and others. There is a long list of composers who have meant something to me. Just look at the composers I have written about. It’s a very long list.

At different points in my life composers have interested me for two reasons. Either they offer me some new possibilities, let’s call them ‘technical’ in the broadest sense of the word. My interest in time and tempo quite naturally led me to Conlon Nancarrow, for whom tempo is in itself a dimension worthy of investigation. This didn’t turn me into a grovelling Nancarrow fan like Ligeti, who calls Nancarrow the ‘Bach of our time’. But Nancarrow’s techniques have been of vital interest to me.

Or, composers may change my mind models. I have been concerned with Stravinsky throughout most of my adult life. I was attracted by Busoni’s theories of music. I am attracted by Satie, again, as a ‘thinker’ because in the case of Satie we may question to what extent the music is music at all, if maybe it might just as well be read or perhaps should be perceived in a third way, beyond plain listening. What happens in his pieces is not always terribly interesting to hear. And yet Satie’s importance for Cage, for example, is enormous, so there must be something going on here, there is something behind the music.

My interest in Scelsi and Nono also has to do with the feeling that this music is something more than sound as sound. It is sound turned into pure spirit, so to speak, it is sound that becomes and creates a spiritual awareness in our heads. And perhaps we approach a pivotal point in our conversation here, for I imagine that the misconception of me as some kind of ‘superintellectual’ partly reflects my enduring conviction that, as it enters our ears music is fused with something that I, for want of a better word, have to call ‘thinking’.

That may sound as if I say that the merry and enjoyable art we call music is only interesting—even physically—when it can be experienced as something philosophical or intellectual. But that would be a colossal distortion of my concerns, for obviously music remains present as sound, and I, too, listen to it and relish it as sound. I simply want it also to create a spiritual perspective in the broadest sense. Yes, that does sound a bit lofty but we don’t have very many good words for it.

AB: What do aesthetic descriptions mean to you? Ones like, individuality, craftmanship, interference, concentration, simplicity, emotional strength?

KAR: Some of them I recognize as something I have often returned to. I have often recommended that we substitute the word ‘individual’ for the boring half-German, philosophical word ‘original’, because, all of a sudden, it becomes something quite plain. Each of us has his own way of appearing, of walking, moving and so on. Altogether it’s what we could readily call our individuality. Everything that is specific without being premeditated. That kind of individuality doesn’t have to be construed as ‘originality’, it is something almost unavoidable. But when Stockhausen goes to great pains trying to avoid doing what someone has done before, I don’t see what that has to do with individuality. It’s something which is, to use his own language, ausgedacht, thought out, it seems to me.

If an artist loses touch with his own individuality then it’s probably due to exposure to some form of thought-terrorism or group-pressure, some mind-control police who tell him what he should not do and what he ought to do. Therefore it is also important for me—even though I don’t think I have previously mentioned it in public—to consider my own roots. My particular history, my background when I began to compose has actually marked the whole course of my composing career. Not as a result of some intellectual stance with respect to cultural or political things, but as a simple expression of ‘my way’. And when I realized that this was what made composing fun and interesting for me, I continued in that spirit. Perhaps you can say that I am still trying to find new ways of using that specific potential.

I don’t really know what ‘craft’ is. As a teacher of composers for many years though, I think I know that craftmanship means something. If I didn’t believe that there was something that could be learned, it would be meaningless to teach. But it would never occur to me to say that I could teach someone to compose. I will say that at most I can possibly teach someone to think as a composer.

What that means is having an expanded and finely-tuned awareness of how difficult it is to compose, instead of thinking that it’s like a cow giving milk. This, I think, is an important condition if an artist is to gain perspective. This is not to say that those blessed by God to give milk are insignificant; sometimes they are the most significant of all. However, composers apply to conservatories of their own free will, so they obviously wish to be influenced in some way. Often they only wish for—what shall we say—a coach who stands there on the sidelines and can see a little better from a slightly different angle. Composers have intentions and the craft is the ability to realize these intentions without relying on others. What were the other words?

AB: Interference.

Interference is a word that reminds me of a long discussion I began with Per Nørgård some time back; we call it our ‘eternal’ discussion. We imagine ourselves as two different types of composers. There are those who seek to discover where a particular music is moving. They proceed ‘ecologically’; they don’t wish to interfere with the material more than is necessary. Mozart is an example. Or Morton Feldman, who said somewhere that ‘every time I try to manipulate my work, for what I think is a terrific idea, I know that in a minute I’d hear my music screaming “Help”’! These composers experience their music as something with its own life, like a woman who has a child in her belly. There isn’t any point in her working energetically to make it into a girl or a boy or a genius. The best she can do is to have a healthy life-style and take some long walks so the child will be strong and well.

Then you have another type of artist who thinks that interesting things happen precisely when they interfere. At this point we have to abandon the embryo image. I’m not speaking of genetic engineering but about the kind of art where you establish something and then react to it. Examples? Haydn, Stravinsky, naturally also Kirkeby, whom we mentioned above.

It is characteristic of my own temperament that I react. I said earlier that I think best when I’m talking with someone, or when I am in a discussion, because it gives me the opportunity to relate to something. My creative instincts work in the same way and that explains the countless works—if more rare now—in my output where I start with something extant that I develop further.

AB: Concentration.

KAR: The creative process is essentially one of concentration. A composer said that he always writes with ink because ‘As soon as I begin to cross out, I’m not concentrating any more’? To which he added, ‘If I get inspired, I go for a walk’, implying that when you are inspired you can no longer concentrate because you will lose control. You have to write the notes that you really mean to write at each single moment. Some composers work with a rubber, and it is obviously their right. However, it is always better to work in a concentrated way for five minutes than to sit and push notes around aimlessly for many hours.

AB: Simplicity.

KAR: I don’t know what that is.

AB: Emotional strength.

KAR: Nor that either.

AB: Those six categories are the chapter titles in what you called ‘My Catechism’ (Dansk Musik Tidsskrift, 1978, ed.). It seems that you don’t have anything to add today—or do you? But evidently, you do have something to strike out.

KAR: Well, yes . . . that is twenty years ago, right? Or something like that.

AB: Yes . . . nearly twenty years.

KAR: Well, anyway I’ll ‘stand by’ simplicity as a somewhat banal category. If you want to say something then say it as simply as possible. I hope that those who read my writings will agree that I try to do this. I try to write simply, even on complex issues. Don’t make things more complicated than necessary. That’s what I understand by the word, simplicity.

But emotional strength is simply so completely tied up with experience that it is a private thing. Kierkegaard used a brilliant distinction between the things you can only do first hand and the things you can do second hand. If I were to write an article on Italian foreign policy, I could ask a friend to go to Italy for me, gather material, possibly interview some politicians, and so on. Based on that I could write the article. It is something I can do second hand. But I can’t attend a concert second hand. I can’t send you in there to hear the concert for me. I can’t ask you to date my sweetheart for a few months because I am away on a trip. These are things I can only do first hand. Someday when Death knocks at my door, I won’t be able to ask my neighbour to deal with him.

Emotional strength is something a listener can experience only first hand, and therefore it’s not something the composer can put into his work. I can’t imagine a method that would assure a composer that his work acquires emotional strength. If he insists on trying, the risk is that the work becomes sentimental which is something completely different. So when I say that I don’t know what emotional strength is, I mean that I only know what it is when nobody asks me. I haven’t struck it from the list, I have just become a bit wiser, maybe, about where it belongs.

AB: In the 1980s you wanted to ‘make a music that wonders . . . or makes people wonder’. In the 1990s I detect a new poetic dimension to your expression, something that extends further toward the listener. I have the feeling that you are no longer satisfied with making people wonder?

KAR: That’s probably true. I think there was a phase in the 1980s when my instinctive critical attitude was particularly strong and today I find that the least interesting phase in my output. While I have some nostalgia for the works of the 1970s there is a period in the 1980s that honestly doesn’t interest me very much to-day. Perhaps I let myself be overpowered by cultural politics, ideology and non-musical notions. I have lived so much of my life as an animator and teacher—it’s hardly surprising if these activities at one time or another impact on my creativity in a negative way.

It doesn’t surprise me that it could happen, but rather that it lasted for some time. When I look back on my work, I usually see clear lines, not in the sense of causal relationships but simply natural movements in different directions as my interests slowly shift and change course.

AB: It doesn’t seem wholly unreasonable to see a break with the 1970s aesthetic in your work A Symphony in Time (1982). Jørgen I. Jensen described it as a harbinger of ‘an important widening of horizons, not only in the composer’s own development, but also in the larger picture of today’s musical and cultural climate’. That is a grand statement! What happened then?

KAR: The important junctions in my life appear when I come to a point where I can’t figure out how to go on the next day. Usually this sets off some kind of analytic activity, sometimes involving the work of other composers. It happened in 1982 or 1983, not least as the result of annoyance with the way in which cultural politics, writing for the media, and pedagogical concerns began to preoccupy my mind. This led me to reconsider a number of things—particularly Stravinsky.

I began to look at Stravinsky to find out what it was that was going on in certain works that made them particularly fascinating to me while others paled. I couldn’t figure out what my favourite works had in common. For example, what connects the Symphonies of Wind Instruments and the Fairy’s Kiss, despite their obvious stylistic differences? As I became more and more engrossed in this music, I discovered what the similarities are: not just the stereotypical Stravinsky-style cubism of forms and building blocks, but the experience of time itself and the perception of movement.

We tend to think that music moves, but at the same time we have a feeling that it is a metaphor. For how could it actually do that? Classical tonality has certain built-in driving forces. Harmonic tension and release produce an illusion of movement. And the history of modern music is, among other things, the history about searching high and low for something to replace this worn-out engine.

But Stravinsky didn’t use functional harmony. I did a radio programme where I found certain time-proportions in Stravinsky, some precise durational relations between adjacent musical segments, or between segments that are repeated at separate points in the course of the piece. In the Symphonies of Wind Instruments I found incredibly precise relationships between the duration of the individual segments, in other words a very meticulously planned pattern of proportions. And I imagined that this was the key to the kinetic energy of this seemingly static music.

This was the starting point for A Symphony in Time. I expanded this idea of ambiguity, identity and time from a one-movement time-span like Stravinsky’s Symphonies into a larger symphonic form. I imagined that we were in a circle with all four movements in a symphony surrounding us. Elliott Carter has a work with a title that resembles mine—A Symphony of Three Orchestras—in which each of four small orchestras simultaneously plays its own symphony. The thought of taking time apart captivated me. We hear four movements one after the other, but we also hear four movements each one of which, at any given moment, could be one of the other movements. That was my line of thinking and I started to work with Stravinsky’s discovery that proportions of time can create an illusion of movement. I worked very matter-of-factly with very simple material and this resulted in a work that became an important new beginning for me.

AB: How much do you demand from the listeners with this work? I wonder whether, after having heard the four movements, you are supposed to be able to put them together mentally. Or is it so that you can listen to them in isolation from each other? Do you get another and more legitimate experience if you can perceive them together as a whole?

KAR: I don’t know. I’m reluctant to give recipes for the best way to experience something because I know that most often when I find my own way into something, I get the most out of it. I have rarely derived pleasure from listening-recipes myself. When it pertains to works by others I may act as an ‘interpreter’ because sometimes I can help with opening up a door. But when it pertains to my own music, I don’t like doing it. I assume that you can hear the piece as four regular movements without suspecting any special relationship between them.

Let me give you an example. Dennis Potter’s masterpiece is the fantastic TV drama called The Singing Detective. Here something happens that is strikingly similar to what happens in A Symphony in Time. We find ourselves in a kind of time continuum, we never know exactly where we are—whether we are before or after, whether we are in a hospital with the main character, whether we are in his childhood or whether we are at a much later time. I believe that Dennis Potter would feel equally at a loss if you were to ask him ‘How should I view this piece’? You should simply see it because you can’t avoid noticing that time behaves in a peculiar way. I am not at all sure that you can get more out of my symphony by having it explained that one movement is inside another movement, and so on. But you hear a symphony behaving quite differently from most, while, at the same time, it behaves exactly like it should because it has an allegro, an adagio, a scherzo and a finale.

AB: But earlier you were considering the question of how to justify the fact that one note follows another. Your reflections concerning time and your analyses of Stravinsky have made it possible for you to continue along that path. When one reads your articles and essays there is one element that runs throughout. To quote, you say, ‘To want to search after time is like searching after dark with a candle in your hand’. Time has preoccupied you, but to what extent has there been a correlation between your theoretical explorations of the phenomenon of time and the actual music that you have created on the basis of these theoretical considerations? To what extent can these meta-reflections on time be heard in your music?

KAR: Presumably not at all, because that’s not how it works. The way time enters the work—if the experience of time can be in the foreground at all—is in the form of a music that has some special time-related features.

Where is the experience of time actually strongest in music? Probably, in the tempo. In many languages the word for ‘time’ and the word for ‘tempo’ is actually the same. But the tempo is a very difficult thing to isolate because tempo is a kind of conveyor for everything else. It wouldn’t make much sense after having heard a piece to ask, ‘Now, what did you really think about the tempo’? Well, if it is a performance of a well-known work then you can discuss whether or not the performance found the proper tempo. But if you heard a piece for the first time and the composer came out all excited and asked if you had experienced the tempo, I think most people would be baffled. For the tempo is there, it is impossible to imagine music without some kind of tempo; time has to pass.

How can you focus on the tempo as such? When I ask myself that question—and answer it quite unscientifically from my own experience—I find that it happens when the tempo isn’t linear, regular, or constant, so to speak. The experience of tempo is strongest when the tempo is in a state of change, when it gets faster or slower or perhaps swings in and out as it does, for example, in a Chopin-rubato.

If the experience of tempo is particularly strong when the tempo is in a state of change, wouldn’t it be exciting to imagine music that is constantly accelerating or constantly slowing down? Probably, but here I stumble on a technical problem: when the Russians sing their well-known ‘Ka-lin-ka, Ka-lin-ka’ the tempo accelerates so rapidly in a short space of time that the music soon becomes meaningless. Consequently, I have to find a musical strategy—and here you see the connection between thinking and numbers—enabling the tempo to increase or decrease endlessly. And here I get no support whatsoever from philosophies of time, astrophysics or anything like that.

Here I am left with my own theoretical and technical knowledge, and my imagination. And so music may result that either shows that the idea does not work, or perhaps shows that it works up to a point—or maybe that there is a long way to go before it works with great clarity. But who knows, perhaps it isn’t really important whether it works with great ‘clarity’.

In 1979 I wrote that in the 1980s time will be in. And that may be the closest I ever came to being a prophet. It became almost stylish in Danish music to be a pursuer of time and to see the experience of time as a central concern. We must have felt that this was a virgin area where the experience of time, the concept of time and new time-horizons established not only a new conceptual basis but a direct starting point for the creation of new mind models. And as so often, Per Nørgård had already taken the first important steps.

A series of new mind models emerged, and most important for many and certainly for me, probably, were the so-called ‘fractals’. When you begin to think about infinity not as something scary out there in space, but as something down-to-earth—like that cute drawing on a familiar oatmeal box of a little boy who runs with a packet of oatmeal that has a drawing on the oatmeal box of a boy who runs with a packet of oatmeal that has, and so on—then infinity is no longer frightening, but something almost touching. And when all of a sudden it works as a background for new thoughts, I am precisely where I want to be as a composer or artist.

That is where the technical, the audible, the analytical and the conceptual meet in an area which makes room for exploration, stimulates the intellect and, at the same time, offers new shades of meaning that may give rise to new emotions. You use yourself as a kind of test case, I suppose. And perhaps you discover, as you said, some new psychological and poetic dimensions without precisely knowing what they are or where they come from. I don’t think that there are any specific tools other than personal experience. When you test a long series of possibilities, sooner or later you will be able to cope with them and maybe even express something with them.

AB: We have to round this off. I would like to explore the poetic dimension further. I believe that somebody—perhaps myself—has written that when you (by ‘you’ I mean, for example, you and Poul Ruders) threw out collage and style-references, your works became more elevated. I recently heard a piece by you at Tivoli played by the violinist, Rebecca Hirsch. It made a profound impression on me, precisely because there was a poetic dimension in the work.

KAR: It is difficult to talk about this in a general way, because each single work has its own background, history and problems. The piece you refer to actually has an unusually long, poetic title. It is called Sinking Through the Dream Mirror. And I am in a slightly uncomfortable situation because I can’t really explain what it means. The dream mirror is something I have dreamt, or so I believe. I imagined that dreams and reality meet in a ‘mirror’ akin to the surface of water.

The piece uses ‘fractal’ melodic lines, that is to say, identical lines that form a veritable Chinese box of tempi, both very fast and very slow, endlessly intertwined and fitting into each other like a huge network. When such a melodic line falls, sooner or later it will flatten out. If a very fast melody falls in terms of pitch, and a very slow identical melody fits into it—well, it’s clear that the slow melody cannot fall nearly as fast as the fast one can. Thus sooner or later the slow one will make the fast one level out. And this ‘level’ I came to perceive as the water-mirror—a mirror that the melody can break through only when the composer ‘interferes’.

This shows again how theoretical thought inevitably pervades even purely expressive realms. And this simple symbolic idea actually gave the piece its title. But it belongs to the story that it was composed just before I embarked on the opera, The Sinking of the Titanic, and that it is likely to be a premonition of the Doomsday mood that prevails in the opera.

I can’t explain why the work has such a prevailingly melancholy mood, though. You can’t, as I said earlier, wilfully put something like that into a work. In my recent orchestra work, Scherzo with Bells, something ordered and systematic collides with something irrational: a rushing scherzo collides with tolling bells—for me a simple symbol of fate and death. In this case the psychological dimension is easier to explain but for that very reason it may also be less profound. However, if this psychological dimension is what you call the ‘poetic dimension’, then I agree.

AB: You feel particularly at ease in Rome—at one time you increased the number of your trips and started living there for extended periods. Do these voluntary exiles mean that you simply work best there? Was it the crisis that you experienced in the 1980s, or were you bored to death by the Danish music scene?

KAR: The latter certainly is not very pertinent. I am neither bored by the Danish music scene, nor especially charmed by it. The main reason why I began escaping to other skies was quite plainly that I wanted to work where fewer people were likely to disturb me.

Rome as a cultural centre has attracted many Danes throughout the centuries. But I see now that there are some simple, almost musical reasons that meant Rome was the place for me. I’m thinking about the city’s very special soundscape. If you were to say that to an Italian, he would be startled because he recognizes only one version of the sounds of Rome and that is a hellish din. But that isn’t the only Rome. The historical Rome that I ramble around is not particularly polluted by noise. On the contrary, there are squares, small streets and alleys that empty out onto smaller squares that again expand to larger squares, and so on. That results in a constantly changing soundscape, which, in one way or another, keeps the sense of hearing unusually awake.

I thought about that when I walked over here with a friend for the meeting with you today: how difficult it is to have a conversation in the soundscape of Copenhagen. As soon as you enter one of the many main thoroughfares you almost have to shout at each other. It’s stressful, acoustically speaking. In Rome the heavy traffic is kept out of the narrow streets and you travel on a kind of sound stage that changes height and character in a very unexpected and fascinating way.

This soundscape has become my way of staying fond of the city, for the city is, in a strange way, both the theme and the trauma of my life. Since I was about twenty I have lived on a lonely isolated farm in mid-Jutland and I don’t think I’ll change that until they carry me away from there in a box. But like most people, I have a need for something other than peace and quiet. Rome became the place where I could live a completely different life. If I travel alone to Rome and stay there for a month there are very few demands on me—other than the ones I make on myself. I can determine my own social calendar and mostly direct my life in the way in which I find it most fun to live.

© Anders Beyer 1997.

This interview was published in two parts: ‘Modviljens poesi: Samtale med komponisten Karl Aage Rasmussen’, Dansk Musik Tidsskrift vol. 72, nos. 1 and 2 (1997/98): 2-10, 46-54.

The interview was also published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000.

See also Anders Beyer, ‘Toner er mere end blot musik. Et portræt af Karl Aage Rasmussen’.

Biography

Karl Aage Rasmussen (b. 1947, Denmark) studied composition with Nørgård and Gudmundsen-Holmgreen at the Århus Academy of Music. In addition to being a widely-published essayist and active as editor of journals and Danish Radio programmes, Rasmussen occupies a central role in Danish music. He has been the artistic director of the annual NUMUS Festival—famous as an arena for discussion and the exchange of ideas. The concise and penetrating critical thought that characterizes his music is also evident in his other work. Edition Wilhelm Hansen publishes his music and dacapo, Bridge Records and PAULA have issued recordings with performances by ensembles such as the Arditti Quartet, Speculum Musicae, Capricorn, and the ensemble founded by Rasmussen, The Elsinore Players.