Interview with the Composer Karlheinz Stockhausen

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: Looking at your work in the context of the development of music composition in this century, it’s obvious that it broke new ground in a number of areas, for example electronic music, pointillist music, serial music, intuitive music, music theatre, right up to the current multi-form formula composition. The closer we come to today’s Stockhausen, the more formula thinking comes to the fore. But isn’t it now a question of refining the existing technique that you have achieved, producing a kind of concentration of all the compositional techniques and aesthetic experiences that you have collected over the course of your years of experiment in so many areas? How would you describe your music now, at the beginning of the 1990s?

Karlheinz Stockhausen: In the first years of the decade I was still composing DIENSTAG aus LICHT (TUESDAY from the cycle called LIGHT). Towards the middle of the 1990s I will compose FREITAG (FRIDAY) and MITTWOCH (WEDNESDAY) and at the end of the millenium and the beginning of the next I will, God willing, compose SONNTAG aus LICHT (SUNDAY). Since 1990 – without a break – I have been composing and realising the electronic music for DIENSTAG at the Electronic Music Studio of the West German Radio. It is finished, but in the process this work led to so many new questions and tasks that I will be kept busy for years perfecting these new discoveries. I am thinking of the OKTOPHONIE (OCTOPHONY), as well as a new musical technique and forming of dynamics. This gives the music a completely refined relief.

Furthermore, since 1990 I have continued to develop space music (Raum-Musik) beyond octophony, to the extent that the actual movements of the instrumentalists and singers through the audience are composed for the first time. Examples of this are found in the second act of DIENSTAG aus LICHT, which is subtitled INVASION – EXPLOSION mit ABSCHIED (INVASION – EXPLOSION with FAREWELL). In the INVASION a first wave of invasion comes from the left, passes through the audience along three passages and disappears to the right. Next, after an interlude of electronic music, another wave comes from the right and crosses through the hall moving to the left and toward the front. One battling trumpeter falls on the stage in front, and this occasions PIETÀ, a duet for soprano and flugelhorn, performed with electronic music. Then follows a third INVASION that moves from behind the audience along three passages toward the front. In a theatrical performance the stage is finally blasted open. In a concert performance a choir enters from the left and right side of the stage; the men come first, then the women. SYNTHI-FOU, a crazy synthesizer-player – my son, Simon – plays an extraordinarily lively and varied solo along with the electronic music.

I thus composed vertical space music, including all conceivable movements upwards and downwards, as well as space music played by musicians who move through the audience in all possible directions. To this is added the composition in completely differentiated dynamics which I have only just started. In 1992, from January through March, I will again be working at the Electronic Music Studio and for the first time I will be able to work out everything. That will be a whole new, far from easy, task.

AB: So far, I have had the opportunity to attend three parts of the gigantic LICHT, that is, DONNERSTAG (THURSDAY), SAMSTAG (SATURDAY) and MONTAG (MONDAY). Can you describe those parts of the cycle that have not yet been performed?

KS: You mean FREITAG, MITTWOCH and SONNTAG?

AB: Yes.

KS: I call FREITAG aus LICHT the ‘day of temptation’. Here I will represent archetypal human temptations in music. These are, in the first place, the temptations to use the body as a musical instrument, including, therefore, the variant of exchanging human bodies. Unusual experiments with the body are significant human temptations. To use the body itself carefully, like a composer does an instrument.

The other thing which fascinates me is the temptation to transform oneself, in the course of which therefore, one musical situation – in very gradual degrees – is transformed into another one: vocal into instrumental, instrumental into electronic, electronic into surrealistic sound, and so on. To this end I will experiment with the simultaneous realization of several widely divergent sound scenes (Tonszenen) in the same space where they then will be interconnected – not only musically but also by means of physical bridges, whereby the elements are exchanged, multiplied and so forth. This is a very interesting endeavour, one that I have never tried before and that I have never experienced anywhere else; it is, in fact, an attempt to realise a truly poly-scenic composition.

In FREITAG the main task will thus be the creation of pumping sound-reliefs in front of, to the right, left, behind, under and above the audience. Sounds will not only be simultaneously connected along lines or by layering, they will also be parts of a sound-wall that pumps forwards and backwards. For the moment this can be realised with only up to eight components. That’s what I will start to experiment with in January, and we will then see how far I can get. That is FREITAG.

Next comes MITTWOCH. I have had sketches ready for all the days in LICHT since 1977/78, and in those for MITTWOCH I explore the idea of a ‘heavenly parliament’, something I heard and saw in a vision one night. The most important implication of this is that I have to invent a new language because I am convinced that the languages of existing music theatres in all cultures are essentially tied to everyday language. Sure, there already exist – in my own works, too – certain unusual extensions or compressions of time, as well as instances of phonetic imaginary languages, for example, in LUZIFERs TRAUM (LUCIFER’S DREAM) from SAMSTAG aus LICHT. But what I want is a new grammar, a new syntax and, of course, a new rhetoric combined with new words. More than that, a whole new vocabulary. I am going to use many words that are syntheses of various extant human languages, like at the beginning of LUZIFERs TRAUM. For an example, I may construct a word which has three phonetic components that are respectively German, English and French. Furthermore, there will be abstract words that, as yet, do not exist, since a heavenly parliament must of necessity have a new hyper-language that is purely musical in its nature, yet carries meaning. The sense will only be partially perceived, but I believe that that is an interesting problem. It fascinates me, for I have come to realize that all traditional languages are largely dialects of one spiritual language that is common to all human beings.

What inspires me now is that, in connection with MITTWOCH, I would like to compose a language that is not like Esperanto, in other words, not an ‘extra-language’ but a language that comes from existing languages and additionally from a phonetic nonsense-language to form a composite hyper-language. It is an enticing project and, as you can imagine, one that has its humorous moments. I realize that I will take the idea of the parliament into the absurd, as it is made up of spirits who attempt to shape or organize the world merely by speaking, singing or shouting – doing everything possible with the voice. That is, in fact, what most people do nowadays, and it is generally considered to be real work though it is nothing but phonetic manipulation of what others are supposed to do: a very strange attitude toward human work. Let’s have lunch.

[Later]

KS: Within the seven-day LICHT cycle, the theme of SONNTAG is the mystical union of EVA and MICHAEL. Where MITTWOCH is the day of co-operation and mutual understanding, SONNTAG is the day of mystical union. With SONNTAG I have assumed the task of composing a musical planetary system where the proportional lengths of layers of time correspond to the rotations of the planets around the sun in our solar system. In terms of visual space, this is not an easy job. I will obviously need a very large hall where objects move around each other and around a centre, just like the planets and the moons move around each other and around the sun. They also have to have a large distance between them.

All in all, it will look like a large model of our solar system, with the notion that all the planets are inhabited by musical spirits, namely, singers and instrumentalists, and that they are all equipped with windows so that you can travel from one planet to another and maintain contact with each other. In short, it is a mixture of comedy and modern musical temporal composition. As for the musical language, timbre, dynamics, and ‘crew’ of each planet, you can already imagine that I will use these to give each planet its specific character. I have already written extensive sketches, but what I have said may suffice to give you a general idea.

Perhaps you could also expand on the subject of DIENSTAG, because it is going to be premiered in Milan in 1992, and Danish audiences know very little about this portion of LICHT.

DIENSTAG aus LICHT was commissioned by La Scala in Milan after the first performance of MONTAG. Now, you say that the work will be premiered in 1992 in Milan, but that has unfortunately been postponed. Some time ago, I received the message from the new general director, Fontana, that DIENSTAG will not be staged in Milan in 1992, supposedly due to lack of money, although DIENSTAG is far cheaper than those three parts of LICHT premiered earlier by La Scala. But a new opportunity has opened up, and it is likely that DIENSTAG will be given its first performance in Germany in June 1993, and subsequently in Milan in 1994, as a co-production of a German opera house and La Scala. I am not free to reveal the name of the opera house since there is no definite contract, but I think it will come to fruition. Before that, DIENSTAG will receive a number of concert performances.

The first part has already been premièred, in 1988 at the ceremony celebrating the 600 years since the founding of the University of Cologne, at the large Philharmonic Hall of that city. This part, entitled DIENSTAGS-GRUSS (TUESDAY GREETING), or FRIEDENS-GRUSS (PEACE GREETING), is for mixed choir, solo soprano, nine trumpets, nine trombones and two synthesizers. It portrays a musical battle between two large groups. One group consists of sopranos and tenors plus nine trumpeters and one synthesizer player, the other of altos and basses, nine trombonists and one synthesizer player. The groups are positioned at the right and left, behind the audience. The soprano walks around in an effort to bring the strife to an end. This first part of DIENSTAG aus LICHT lasts 21 minutes. It is preceded by yet another brief greeting entitled WILLKOMMEN (WELCOME) for the same instruments that I have just enumerated.

The first act of DIENSTAG aus LICHT was composed already in 1977 and is entitled JAHRESLAUF (COURSE OF THE YEARS). This was the very first part of LICHT, and it was premièred at the National Theatre in Tokyo with the Japanese title, Hikari, which means ‘light’. It was composed for gagaku ensemble, gagaku dancers and five actors. Based on this I wrote a European version with instruments to correspond to the gagaku instruments; this one has subsequently been performed in concert version a couple of times.

An expanded version of this work – for DIENSTAG aus LICHT – with two singers (a tenor and a bass as MICHAEL and LUCIFER, respectively) was premièred this year [1991] on September 29th (St. Michael’s Day) at the Alte Oper in Frankfurt. By then, JAHRESLAUF was integrated as the first act into DIENSTAG aus LICHT. The instrumental version, that is, without singers, dancers and actors, continues to be presented in concert performances under the title, DER JAHRESLAUF (THE COURSE OF THE YEARS).

JAHRESLAUF, the first act of DIENSTAG, is essentially a dispute about time and timelessness. Within the framework of LICHT, DIENSTAG is the day of strife and war, the day of Mars. Therefore, the theme is Lauf des Jahres (course of the year). One group of musicians plays the music of the Jahrtausend (Millenium), which is furthermore personified by a dancer. He moves only once during the entire performance (that lasts about an hour when staged and about 50 minutes in a concert version) – for example in 1992 – over a giant-sized number one that is visibly elevated towards the back of the stage so that it can be easily seen. The Millennium-Runner is costumed appropriately in completely neutral white. Behind him sit three musicians each of whom play a shô, a gagaku-orchestra instrument; in their stead, the European orchestra has harmoniums. In the most recent performance three synthesizers replaced the harmoniums and they sounded like harmoniums or the shô.

A second group of musicians plays the music of the Jahrhundert (Century). In the gagaku-ensemble they are ryuteki players accompanied by a shoko drummer and in the European ensemble there are three piccolo players and a percussionist who beats an anvil. The dancer who belongs to this group represents the Century. In 1992, his course will be a huge number nine.

Then there is the Jahrzehnt (Decade) group: in Japan, there are three hichiriki players and a kakko drummer; in the European orchestra, there are three soprano saxophonists together with a bongo drummer. The hichiriki sound somewhat like shawms or English horns, but somewhat shriller. Possibly the Greek aulos was a comparable instrument. The soprano saxophones are marvellous counterparts and play perfectly refined glissandi. There is a third dancer embodying the Decade. In 1992, this will be illustrated by another number nine. The Century-Runner runs nine times over his path, back and forth. The Decade-Runner doesn’t run exactly nine-times-nine courses, that is, not 81; he comes somewhat short of that because there are interruptions during the performances. I think he runs 57 times back and forth; you may check the score. Anyway, he must move faster still.

The runners have appropriate costumes with corresponding colours. As mentioned, the Millennium-Runner is white. Then the Century-Runner is blue; the Decade-Runner is yellow; and the Year-Runner is green. This is occasionally done differently, though.

A fourth group of musicians represent the Jahr (Year). The musicians in the gagaku group play gakuso, biwa and a taiko drum; their European counterparts play electric harpsichord, electric guitar and bass drum. The fourth dancer, the Year-Runner, must run back and forth across his year course more than 300 times for 1992 in order to make the rhythm of the years explicitly clear.

There are four interruptions called temptations in the JAHRESLAUF. LUCIFER, the bass, attempts four times to bring time to a stop by means of enticements, and MICHAEL sets it back in motion each time by incitements (Anfeuerungen). The first temptation is an attempt to prevent the musicians from continuing to play: bouquets of flowers are brought forth much too early, as though the performance is already over; musicians are, quite naturally, receptive to praise. Then, a little angel appears with the request that the audience applaud so that the musicians will continue to play. The audience does applaud, and so those who have come to congratulate the musicians with their premature flower show must withdraw.

The second temptation follows a little later. A cook brings in a large table heaped with marvellous food. Again, this is another temptation for the musicians to interrupt their musical work, a stronger one at that. At the moment when the performers start toward the food, a lion bounces in, runs up and bites the Year-Runner and the Decade-Runner in their breeches making them instantly return to their positions so that the years can resume their course.

Again, after a lapse of time, a third temptation arrives in the shape of a modern automobile that quickly races across the stage with a monkey behind the wheel. Everybody stops in their tracks to watch in fascination, amazed at the performance of this vehicle. The monkey demonstrates the refinements of some brand-new features of the car. Once again, MICHAEL intervenes in the guise of a child who yells: ‘Please play on. Everybody who continues to play will receive 10,000 Marks’! This suffices to make the musicians carry on with the music, because musicians always need money.

So, time marches on, until the fourth – and strongest – temptation, namely sex. An exciting naked woman on a platform rolls on stage to the accompaniment of highly suggestive nightclub music. The performers are completely carried away. At that point, MICHAEL has no other solution than to launch a terrific thunderstorm with lightning and thunderclaps, which also turns off all lights. The musicians are shocked, and, thank heavens, play on. At the end, there is a presentation of prizes for the best runner of the years and a beautiful procession.

After a pause, act two begins, but in a more physical mode. This is where an INVASION, which I briefly described at the opening of our conversation, occurs. It is a physical battle between one group with trumpets, percussion and synthesizer, and another with trombones, percussion and synthesizer. The group of trumpeters includes a lieutenant of sorts, who is a tenor. The trombone group is headed by an officer, a bass singer. They conduct a musical fight assuming highly stylized postures and gestures. There is sufficient time for members of the audience to take mental snapshots of distinct tableau because at times the performers freeze in bizarre positions, after which the battle rages on.

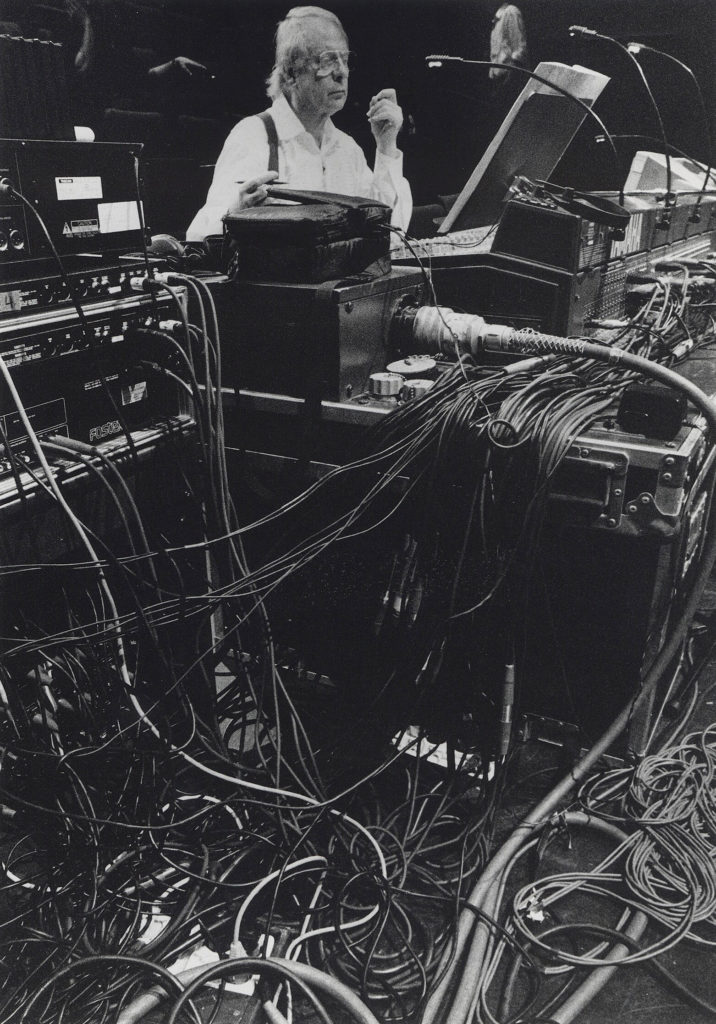

The musicians all play from memory. Two play portable synthesizers; two others carry percussion instruments. They also have speakers attached to their bodies. Samplers, special aggregates and cables are carried by assistants. It functions brilliantly. Via MIDI equipment they play strange sounds on synthesizers and on imaginative percussion instruments that are equipped with touch-sensitive keyboards projecting electronic sounds.

The scene entitled PIETÀ follows the second INVASION during which a trumpeter is wounded. A soprano holds the trumpeter in her lap, but at the same time, the gigantic spirit of this same trumpeter stands behind her. The two sing and play a moving duet, together with electronic music, that lasts approximately 18 minutes.

Following this, a third INVASION blasts open the wall at the back of the stage. Already in the first INVASION a rock wall, complete with shrubs, climbers, even small trees, is blown up. Behind it, a chrome steel wall becomes visible. In turn, this is blown up at the end of the second INVASION. Behind it now appears a rock crystal wall with sparkling crystals. Finally, after the third INVASION, even this wall is blown to pieces, and behind it one glimpses the beyond. One sees a space of glass, completely transparent. Glass-like beings are singing strangely coded messages. These glass-like beings are evidently engaged in a war-game with ships, tanks and airplanes made of glass. These glass objects roll across a vitreous game board between the players who sit to the right and the ones who sit to the left.

The beings in the beyond have croupier-rakes made of glass and push glass soldiers, tanks and airplanes onto a transparent conveyor-belt that carries everything away. The players seem bored. It becomes clear that wars on our planet are only materialized manifestations of war-games played by superior beings. They play war like we do as children with our clay soldiers and other war-toys. The set-up in DIENSTAG resembles a stock exchange. Behind the alien beings, one sees scoreboards on the left and on the right with numbers that register how much military equipment has been destroyed by each party.

In DIENSTAGS-ABSCHIED (TUESDAY FAREWELL), a crazy character enters riding a gun-carriage. He has huge green ears, a long red nose, over-sized sunglasses and grotesque gloves; he plays in the midst of a battery of synthesizers. The carriage swerves around, turning in circles. The Synthi-Fou, as I have named him, plays hot dance-music accompanied by electronic music; however, it’s not really human music but something that’s oddly stylized, with long phrases, completely weird harmonies, extreme rhythmic durations and virtuoso cascades of sounds that blaze with a fiery inner life.

Now, that’s the INVASION – EXPLOSION with FAREWELL from TUESDAY. The glass-like men wave to glass-like women – who are sort of cosmic Red Cross nurses – and the latter join the men on stage. The women stand behind the men (they do not look at each other) and touch only the tips of their fingers; they move in a jerky manner, almost like puppets or robots. In a kind of geometric dance, these creatures of the beyond disappear into the distance until they are no longer audible or visible. This leaves SYNTHI-FOU alone on stage. The point is that even cosmic beings may be distracted or amused by a mad musician, to the extent that they abandon their war-games and listen in astonishment and, eventually, move on to remote regions. However, the penetration of the wall between this world and the one beyond by means of musical invasions merely causes these beings to withdraw further into the cosmos. The result is that one already feels the urge to blow up the next wall by means of music. This is DIENSTAG aus LICHT in condensed form.

In the program booklet for the concert performance of JAHRESLAUF and INVASION in Frankfurt, September 1991, only these two parts are described. The first complete performance at the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon of the entire DIENSTAG with all of its parts will be on 10, 11 and 12 June [1992]. A year and a half ago we gave a series of 14 concerts there; we performed SIRIUS three times, then followed that with 11 concerts, each with a different program. That was fantastic. Nearly 15,000 listeners, mostly young people, searched us out in the beautiful auditorium in Lisbon. That’s where we shall give the three presentations of DIENSTAG. We will be travelling there together with the student choir of the Cologne University and all the soloists – I believe there are 31 solo singers and instrumentalists – and we will work there for six days: three days of rehearsals and three performances. That will be the first complete performance of DIENSTAG aus LICHT.

Following that, we will travel (on 25 June) to Amsterdam to give another concert performance at the opera house (possibly followed by a second one, 26 June). As mentioned, the first staged performance will likely be at a German opera house in June of 1993, though I believe that it may possibly happen earlier at the end of May. Then DIENSTAG aus LICHT is ready.

AB: Your description of the whole war machinery in DIENSTAG leads me to ask if the work itself reflects the contemporary world? Does it mirror actual events you have lived through?

KS: The history of our own time doesn’t interest me very much. The seven themes of the seven parts of LICHT are essentially beyond time and are not tied to events of the 20th century. Their real meaning is as follows: MONTAG is the day of birth, veneration of the woman, the day of children; DIENSTAG, the day of conflict and war; MITTWOCH the day of co-operation and mutual understanding – that is, of a new shared language and shared visions. DONNERSTAG in LICHT is the day of learning, of the human process. It starts as a child learns language, learns about the world, the relationship between sun, moon, stars, the experiences with parents, including hunting, war, peace, laughter, crying, singing, praying, and the passing over into the world beyond. In the second act, one experiences a journey round the world aboard a rotating planet Earth which makes seven stops in seven different terrestrial cultures. The third act takes place in the celestial residence of MICHAEL, the Cosmocreator. FREITAG is the day of temptation, as already described. SAMSTAG is the day of death and resurrection, the latter achieved by the transformation of matter into LIGHT. SONNTAG is the day of the mystical union of MICHAEL and EVA. In this way, MONTAG is the sequel to SONNTAG and starts the eternal cycle over again.

In my view, the wars we have lived through only confirm the existence of a timeless legitimacy. For example, war as a conflict between groups of peoples is really war between spirits that are incarnate on this planet. It is thought-provoking that I composed the INVASION and the EXPLOSION in a period of high international tensions. I finished the work on 14 January 1991, and the following day, on 15 January, I went to Paris to direct a series of performances of my works at the conservatory. I vividly remember getting the morning papers with the headlines proclaiming that the Gulf War had broken out. It struck me as significant that I had finished the work the day before, because that day was followed by months during which the whole world was hypnotized by this blazing conflict in which a great number of people were killed in a very short time and horrible destruction was inflicted on the area. In this sense, I get the impression that my theme for DIENSTAG aus LICHT is relevant to all human beings.

But in a wider sense, everything is music for me – a very important realization. As a child I lived through every day and every night of World War II. For six long years I experienced the fantastic spectacle of warfare in the sky, with air defence and all the different forms of air strikes and different effects of light, and, above all the music that is part of it. During the last six months of the war, as a 16-year-old, I was near the western front, in a military hospital where I helped the wounded. The many daily attacks with various types of bombings produced a completely unbelievable music that went on for days and nights. This taught me that all acoustical events are of interest. What you hear in a war, musical statements that arise from a military conflict, is something that you simply can’t experience in any other way. In that way I experienced war music as a singular kind of music in the widest sense.

I am interested in everything that can be turned into music. Also the music that is present in nature and that I can change into art music. The quintessential elements are always, after all, matters of tempi, musical energies, dynamic gradations, unique kinds of timbres, polyphonic space, movements in space. Add to that movements in polyphonic spaces. For example, INVASION contains a tremendously complex polyphony of sound objects that are fired off and come zooming down from the ceiling at different speeds like sound bombs. Simultaneously, one hears sound grenades which shoot upwards out of the floor and walls while the sound bombs fall. It is a poly-spatial concept, and a fascinating compositional challenge. It took me months in the Studio for Electronic Music to produce these movements of sound with the new technique of OCTOPHONY.

AB: Speaking of technique, I understand that formula composition allows the freedom to work with highly varied ideas. It seems that this formal system is extremely flexible. But that, in turn, implies that at the same time, it can be difficult for the listener to grasp the structure and the meaning of the composition. Is it important for you that the listener captures the complexities of the many layers? Or, have you no great expectations of the audience? In an interview with Gisela Gronemeyer you said that art is for anyone who wants art. Does that mean that you are not concerned with clarifying things for the audience, or, do you expect the listener to sit down and study the music?

KS: I have studied music pedagogy and published six volumes of texts with over two thousand pages and graphic examples about my work. In addition, I have published numerous scores that have extensive prefaces with precise directions for performance practice. In other words, I have had countless ‘conversations’, comparable to this one, and they have been written out and music examples added. You may be familiar with my lecture ‘Die Kunst, zu hören’ (The art, to listen) from volume five of Texte zur Musik, and know that, on the occasion of performances, I have made every attempt to help listeners understand how a work – in this case, IN FREUNDSCHAFT – is composed and how one might listen to it.

For 21 years I taught annually at the International Summer Courses for New Music in Darmstadt where I analysed and explained my works. I am, indeed, greatly concerned that the listener should know how to listen to my music. Still, what you say is also right: I don’t impose restrictions on myself to wait until everyone comprehends what I have been doing before I proceed. Rather, I feel completely free to form music just as I think it should be and in a way that fascinates me. I provide what help I can for the listener, but I know perfectly well that very few exert themselves so as to listen repeatedly, study scores and analyse music. So, to my mind, everyone is free.

There are almost six billion people on this planet. Nobody knows how many will ever be interested in my work, even in a thousand years. It is therefore meaningless for me as a composer to devote a lot of thought to figuring out how many people are going to keep up with me, or how many are going to analyse my works. You have to compose what you yourself can hear and simply expect that someday others will also be able to hear the same thing. I believe it’s best that way. What is typical of our century and largely promoted by the media, is the general belief that everything aired or distributed must be instantly comprehensible. But that’s an enormous misconception. It’s rooted in the assumption that there exists such a thing as the public. We must correct this view and make it clear that people are individuals, each following a unique path toward learning and development, each one free to make personal choices. Let us be less eager to teach and to prescribe rules of conduct, and rather just state: ‘If you want to listen, you can; here are the recordings and scores. We give concerts; we will provide information if you are interested and become involved, but it is your own choice’.

We know, of course, that the overwhelming majority of our contemporaries are interested only in very simple, entertaining music. That’s maybe the way it has to be. But it is a shame that the current, misdirected interpretation of democratic ideals has led most people to believe that only the taste of the majority has merit, and that an ingenious and very futuristic development of the arts is impossible in our times. This ought not happen, in my opinion, for it means that mankind no longer knows where it is going. Then we will be stuck at our present level. I cannot accept that this should be the meaning of life. What is meaningful in life is that one learns something new every day in order to stay alive and not end up spiritually dead. In the short span of a lifetime, one should strain to acquire as much new knowledge as possible and remain wide open to future developments of mankind and constantly develop oneself, sensible to persistent progress toward a higher stage of humanity. To further this goal is a prerogative of art music, provided that it is very carefully composed, innovative and demanding.

AB: Speaking of the dissemination of your music, there is the problem that you work with elite players. Since the music is so demanding, few musicians can adequately perform these pieces. Your son, Markus, performed in Copenhagen recently and demonstrated that it is possible to execute your highly varied tempo changes. It seems unbelievable but when you hear it you realize that it is possible. I know that many musicians are scared of performing your works because they find them extremely difficult. There is only one designated group of musicians who travel around performing your music. Doesn’t this set limitations on the wider circulation of your work?

KS: Probably. However, until now there have also been very few individuals who have travelled in outer space, but with time there will be more, and that will bring an important opening up of our planet to the universe. It is the same in music. There are always those who have to go first and show what is possible. These pioneers then have students. The performers with whom I collaborate – instrumentalists, singers, dancer-mimes – now have students. Suzanne Stephens, for example, has already trained four marvellous students who can perform HARLEKIN, dancing and playing the clarinet, non-stop for about 45 minutes. And very well, at that! So, we see the slow beginning of a completely new chapter in music history. Important developments in history always start small.

Anyhow, the most gifted musicians should know what is possible, set their standards high, and work with model musicians. In two to three generations there will then be numerous interpreters who possess comparable qualities. The beginning of a mutation of mankind takes place very slowly. This transformation is no longer tied to one nationality or one country. I work with musicians of different countries and races who come from widely different educational backgrounds. I am not worried at all.

The overall problem today is that there is no money available for the kind of music I compose, including music for the theatre. In Germany, for example, we have about 100 opera houses that give performances night after night. Many of these opera houses have annual budgets of 100 million Marks. That’s a huge amount of money. But they play the regular repertory almost exclusively, and contemporary music theatre only very seldom because they are forced to work within the rigid structure of their organization. This includes an ensemble of permanently hired singers, sometimes expanded with two or three guest stars, and an orchestra. Since the permanently contracted ensemble already is very costly, it isn’t possible to hire more vocalists, instrumentalists and dancers for solo parts.

Many opera houses have something like 45 singers permanently engaged, as is the case at the Opera in Düsseldorf. A singer is paid in the region of 2,000 Marks per month to sing whatever standard works happen to be programmed. A work like one of the operas of my LICHT is not the kind they could quickly learn by heart; in fact, they would have to rehearse it longer than usual since this is something they were never taught at the conservatory. So, they would have to be taken out of the regular routine for a significant length of time (several months, probably) to rehearse that work exclusively.

My works frequently contain directions for physical movements that are more complex than those that a stage director might improvise; these are notated with the same precision as the notes. My works also require the kind of instrumentalist who is not a member of the orchestras of opera houses as they are. In any case, they have their orchestras sitting in the orchestra pits waiting to be put to use. I do not write for the usual configuration of players in a standard orchestra with a conductor; consequently, my operas are not performed. With the exception of second and third acts of DONNERSTAG, the operas of LICHT are to be performed on the cover of the closed orchestra pit.

What’s more, I need electro-acoustics. That means, for example, eight sets of paired speakers in a ring around the audience, and often more than that because the listeners who sit under a balcony can’t hear the sounds from the speakers above the balcony. The architecture of auditoriums in opera houses with balconies and boxes is not well suited to my music, since they were conceived for a kind of opera that is seen from a distance with a single source of sound: in front of the audience is a box that looks as diminutive as a TV screen from the seats of most members of the audience and a Mozart opera, for example is performed in that box – the singers are far away.

Earlier this week, I went to the Cologne Opera and I was astonished to hear how weak the singers sounded from where I was sitting in the 30th row. I also heard very little from the orchestra; the sound from the pit reached me only indirectly. That kind of experience is a far cry from the acoustical effect that I want which is that the sound be truly present as a physical sensation, right next to the listener, clearly perceptible, with everything understandable. I have, as yet, no idea about how the situation might be changed. It would take a revolution to alter social structures to such a degree that other sites, beside opera houses and concert halls, could get a share of available funds.

Symphony orchestras don’t play my music at all. I have composed 39 works for orchestra and choir with orchestra, and they are never performed. Nothing! And that’s the way it has been for 40 years, although we have more than 120 very expensive professional orchestras in Germany. Many of them keep in excess of 100 players on the payroll, they are paid very good monthly salaries. Many orchestra musicians have salaries of 10-12,000 Marks. They don’t play my music. Why? Because a performance of one of my works requires at least four days of rehearsals, even as many as ten days in the case of INORI, a work that lasts approximately 70 minutes.

At the moment, programming follows a formula of 3 or 4 pieces per concert and an intermission. An overture or symphony opens the first half of the programme, before the intermission there is a piano or violin concerto, and the second half is a symphony. In about 90% of all cases, this symphony is by Mahler or Bruckner. The conductors increasingly want works for large forces and the longest pieces on the repertory, so that they can show off their own skills. These conventions leave no room for my works. Yet works like mine exist and there is a need for drastic change in all of those countries where this type of music culture prevails, including Japan which imitates Europe to the letter, even to the point of largely abandoning its own tradition. So, something radically different will have to replace the current spaces, ensembles, orchestras and opera houses.

AB: If, somehow, there was enough money for the project, how would you then envision the appearance of seven opera houses dedicated to performances of your LICHT operas?

On very beautiful, natural terrain you could build seven different, sufficiently spaced auditoriums for LICHT, as well as a complex for storing scenery and props. Each auditorium should be supplied with a circle of loudspeakers in order to project the sound all around the audiences. The seating arrangements in these auditoriums should be flexible so that you could open and close scenes around the audience during performances. The audience could also be seated on a platform, as it was at the World Exhibit at Osaka back in 1970. The height of the audience could then be altered by hydraulics. In the case of LICHT, each auditorium should have a production workshop for preparing costumes and props. Each hall would have its own unique features.

For MONTAG, there would be a space with a body of water, giving the sensation of the sea and a sandy beach. The audience should feel as though it was in a modern hotel by the sea, where a rite is performed around the large Eva figure. DIENSTAG would need a spacious open plane surrounded by large areas for the invasions, as well as a very deep area in front of the audience (that is to say, the direction in which the audience mostly faces). In the INVASION – EXPLOSION act, DIENSTAG requires great amounts of metal. First you see a rock-wall, then a wall of chromium-plated steel, then a crystalline wall. The entire auditorium would be irregular with open areas between blocks of spectators so that performers have room to run back and forth through the audience during the INVASIONS. There ought to be no more than 600 or 700 people in the audience, otherwise the OCTOPHONY cannot be heard properly. The auditorium would also have to be very high so that the vertical movements of the sounds would be perceptible.

Each day of LICHT would pose different demands from the space. If you study the libretti and synopses for the individual days, you will see what materials, colours and spatial layouts are needed in order to hear the works properly. In any case other auditoriums will certainly appear, in which the audiences can hear sounds from every direction: from above, from below, and from all sides, moving around audiences according to the scores – similar to the spheric space at the World Exhibition at Osaka – and with still many more possibilities. These spaces should also have openings, tunnels and adjacent spaces through which performers can enter or leave as needed and into which they could disappear. In this way audiences will truly be engulfed by the sounds, they will feel the sound all around them, and it will be possible to aim the sound projection so that every sound passes close by the listeners or moves around them. This is the future, even if initially it is limited to a few model auditoriums.

Strangely enough, Germany now imports musicals from England and builds new auditoriums especially for them, for example, Cats and Starlight Express by the English composer Andrew Lloyd Webber. And performances are sold out four years in advance. It boils down to a question of publicity. The underlying idea is the theory of mass production. The contents are quite simple pop-songs; it’s just a variant of theatre as entertainment. But this could be refined. Someday new auditoriums will be constructed for LICHT as well. That is a given.

Current opera houses are really only built for operas in the traditional repertory, which includes most operas from this century. There are composers today who still perpetuate the patterns of the classic-romantic opera. I recently heard an example of this, a work by composer York Höller from Cologne, with the title Der Meister und Margarita. For this opera he received first prize for the best new opera from the last six years. Yet it is perfectly traditional: the singers perform on stage as usual and the orchestra sits in the pit. Four tiny speakers in the hall project a few short-taped recordings, but they are barely noticeable. The work follows familiar conventions, and that determines the result. It is a literary opera, with a lot of Sprechgesang and normal speech. The orchestra delivers a plain musical background to what is sung or spoken on stage. The stage decoration is the real show from the audience’s perspective.

Operas from the 18th century are, as a matter of fact, thinly scored; they were written for small, unprepossessing theatres. Of course, you can perform them with today’s larger orchestras, but then the size of the orchestra is simply increased to provide greater acoustic energy levels for large opera houses. So, you still hear every word that is being sung. The singing voice is not covered, as is largely the case in the operas of Berg and Schoenberg; in their works it is already very difficult to understand the text.

AB: Could these seven buildings be placed right here where you live and work?

KS: Sure, no problem. Our Foundation would have enough land. But there would be a storm of protests, because the countryside around where I live is protected. It is not even feasible to get permission to add a room to your own house; the law forbids it. Not long ago, I ran into this problem. I wanted to add two rooms to a small house in order to store musical instruments and scores there; my house is really too small. I had the plan drawn by a local architect, and it was merely a matter of a few square meters. But no, the rooms had to be instantly removed. The regulations are disturbingly rigid.

We may envision a cultural revival that transforms chosen spots on this planet into beautiful, artistic parks, but that goes absolutely against common, socialist-leaning attitudes. The authorities might allow a soccer field, an airport, a zoo or a botanical garden, but then only if everything is orderly, with signs that say, ‘Keep Off the Grass’, and so forth.

You won’t find the instinctive sensibility to comprehend a new kind of artistic space, like that of a splendid Japanese temple precinct. Such a temple is a complex of several structures within a large terrain that includes a garden that is an artistic creation in itself. Japanese gardens are miraculous by themselves and they are surrounded by carefully cultivated woods. In such an area there may also be a beautiful stage that would be used for Gagaku music or Nô plays. But such things would be inconceivable in today’s Europe, certainly in Germany! The predominant view is, ‘We have our opera houses, our concert halls for symphony orchestras, our museums, and that’s enough’.

AB: One doesn’t have to study your scores too closely to realize that structures based on numbers are important in your music. Often musicians will count out loud while playing. It is tempting to compare your numerology with the late medieval cult of the magic square that played a role in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus. How do your numerological principles – or how does constructivism on the whole – relate to your aesthetic, philosophical, even utopian, views?

KS: Anybody who has worked in a modern electronic music studio knows that one constantly operates with numbers: numbers for sound volume, numbers for durations, numbers for pitches, numbers for constellations of timbres (spectra), numbers for spatial movements. In the program booklet for the Frankfurt Feste, in the text on OCTOPHONY, you can read about the fact that any position in space is nothing other than a configuration of numbers for the volume of sound and sequence of speakers.

Years ago, when I was 22, I started to use numbers in musical analyses to replace names for pitches and Italian terms for volume, from pianissimo to fortissimo, in order to simplify the descriptions. The same principle can be applied to durations. I used not only traditional note values but used numbers for all durations that could not be represented in traditional notation. For fractions of a beat I used a decimal point (sometimes followed by complex numbers), which caused Stravinsky to chuckle over this German Professor Stockhausen who wrote, ‘MM 63.5’. And he repeated: ‘point five’! Well, if he had known what he was talking about he might have realized that not just ‘point five’ should have been indicated there, but – with a futuristic Stockhausen-Metronome – 63 point 56778, as, for example, in the case of a tuned pitch on the piano. Naturally, if you want to give a precise numerical indication of the pitches of the tempered scale, then you arrive at complex numbers. Never mind that any child can sing those pitches. The same is true of tempos as well as dynamics.

Last week, while mixing a recording in Hannover, I noticed that even 0.2 or 0.3 of a decibel constitutes an audible difference between different sound sources, if they are to be balanced spatially exactly in the middle. So: You listen until it is correct, and upon seeing what you actually heard you are completely astounded when you learn that the apparatus indeed records a difference of 0.3 of a decibel. Then I write this down. Our ears can be highly discriminating when it comes to spatial orientation. All the characteristics of music can be represented by numbers. When you compose, music comprises numbers, particularly so when you compose with electronic equipment. My son, Simon, selects numbers when he programs his synthesizer. He uses an Atari computer which he must also program exclusively by numbers. When measuring sound, there is nothing but numbers. When we push the study of anatomy to its fundamentals, we know that our bodies can be represented by numbers. Who knows what a DNA code is? By the way, in Europe it is often referred to as a DNS code. Do you know what that is?

AB: We call it DNA.

KS: So do I. Crick and Watson provided a new formulation of the DNA code that had already been discovered in the 1930s. The gene, which calls forth life and dictates our physiological form as well as our characteristics, is known to be a numerical sequence of components. Astronomical events are also described in numbers. They must be exact down to a millionth of a second to be valid. All cosmic events, everything that happens on this planet, all has a material exterior that’s accessible to touch, smell, hearing, vision. However, what goes on between the sensory system and the brain consists of a transformation into numbers. Only numbers exist in the brain, it translates everything into digits. Our most modern computers are merely limited copies of our brains, for the human brain is, essentially, nothing but a giant computer. The small computers we produce are miniature copies of our brains.

When you look closely at human nature and our natural surroundings, you notice that particular numbers are crucial. This is recognized in the Pythagorean number sequence, 1 plus 2 plus 3 plus 4, from which an entire universe can be developed, all based on the number ten. Two times five fingers, as we can see it on our own hands and two times five toes seen from above, show the Pythagorean system. From this, the entire universe is built – 1 plus 2 plus 3 plus 4. That is a series, and the serial order of these four numbers is the key, for if we place our two hands next to each other with the thumbs toward the outside, we get 3 – 4 – 2 – 1 (the two little fingers in the middle), so that no interval is repeated. The intervals are all different: 3 followed by 4 gives plus 1; 4 followed by 2 gives minus 2; 2 followed by 1 gives minus 1; 3, the first number, following the last, namely 1, gives plus 2. It is important to keep in mind that the intervals between numbers are very significant.

In music, this numerical relationship has been translated into serialism. Formula music simply takes this further by incorporating even much more than just the durations of notes, pitches of the notes, intensities of the notes, composition of tone spectrums, and spatial positions of tones (that is to say the directions and decisions concerning with what velocities the tones move around above and below the audience in the auditory space). In addition to all this, a formula includes pre-echoes, echoes, scales, pure pauses, coloured pauses, modulations and improvisations: in short, more qualities of sound. Of course, these qualities of a formula can also be comprehended in terms of numbers. From such a genetic code of music that can be used for composing, it is possible to develop a large organism. That’s what I am doing in LICHT. The only difference from earlier projects is that rather than lasting the usual quarter- or half-hour like traditional music, this organism lasts for approximately 24 hours. LICHT is nothing but a galaxy that’s derived from a single nuclear formula.

In his Kunst der Fuge Johann Sebastian Bach attempted to derive a large work from a single theme by using all the possible manipulations and combinations of that theme. At the end of the 20th century, this principle is being applied on a far more differentiated and complex level to many more parameters than anybody could have imagined in Bach’s time; in fact, to everything whenever possible. It is even applied to the movements of dancers, to costumes, colours, fragrances, spaces – everything. That is an evolutionary fact.

In this sense, formula composition is a refined further development of serialism and incorporates the intermediate phases of aleatoric music and indeterminacy (also known as variable determinism), right up to the latest concepts surrounding parameters that were not even thought about earlier: composition based on the degrees of surprise (Überraschungsgrad), degrees of destruction (Zerstörungsgrad), degrees of renewal (Erneuerungsgrad) and so on. Today all these elements are subject to numerical control in musical compositions. It’s a typical late 20th-century phenomenon and it’s directly related to modern technology; it’s incredibly significant!

Naturally, there are also mysterious relationships involved, as you indicated with your reference to the cosmos. We have not only inherited the Pythagorean system of 1 plus 2 plus 3 plus 4, but also the series of prime numbers have lately become an important factor in music. These are the numbers that are not divisible: 1, then 3, 5, 7, and 11, 13, 17, 23, and so on. Now, traditional music is derived from 1 to 2 to 3 and so forth, where 1 to 2 are the octaves, 2 to 3 are the fifths, 3 to 4 are the fourths, 4 to 5 are major thirds, and 5 to 6 are minor thirds. The major and minor thirds and their inversions, the sixths, were considered vulgar and were called the ‘imperfect six-three chords’ (false parallels). They were supposed to have originated in England where they were initially sung in popular music. (From what I hear, maids in Vienna are about the only ones who indulge in singing parallel thirds.) After thirds and sixths, the major and minor seconds were added, and with them, major and minor sevenths as well as major and minor ninths.

Towards the middle of this century, my electronic work STUDIE II introduced intervals of the 25th square root of 5 into music. The 25th square root of 5 produces intervals that differ significantly from the ordinary division of the octave’s 12 tones into 11 equal intervals. STUDIE II excludes octaves, fifths, fourths and major thirds from its scale. In GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE, I used 42 different scales for individual sections. That gives a completely different kind of melody and harmony, as well as a very different rhythm when these scales are used for determining the durations.

In the last few years I have worked intensively with micro-scales (remind me to give you some scores as a present). That is, micro-scales applied to instrumental music, because I use them for flute, basset-horn and trumpet. I use fingerings that are highly unusual, and which must be learned from scratch by the musicians, as they have never encountered them before, no matter how long they have been playing their instruments. New melodic and harmonic structures occur, and above all, new timbres. The evolution of scales into ever finer, unexplored areas is increasingly important.

Apparently, I was the one who first introduced groups of 11 notes and 13 notes into rhythm. It is believed that Brahms introduced groups of 9, that is, three times three. Though Chopin used a group of 17, he used it only as a cadential figure, not systematically as in my GRUPPEN für 3 Orchester (1958) or ZEITMASZE (1955) where triplets, quintuplets, septuplets, and groups of 9, 11 and 13 (Neuntolen, Elftolen, Dreizehntolen) became just as important as the even-numbered divisions. In later works, particularly of electronic music, there are still much more differentiated rhythms based on irregular and complex numbers. That, in turn, produces other very interesting experiences! Number 7 plays a significant role in my music, as does 11. Everything related to Lucifer is connected with 11 and 13.

AB: Is there a conscious effort to give material presence to the cosmic and the divine within formula thinking?

KS: Well, as I have emphasized repeatedly, formula thinking is not my invention, but is the next step of a planetary development. The millennia-old use of ragas and talas as formative elements of Indian music, or the variations of primal forms in Chinese music, influenced the musical techniques of Central Europe via Greek music. Working with primal forms like ragas and talas is an absolutely fundamental technique. The principle resurfaced in late medieval Europe in the form of isorhythms. The monks knew that, and partly from Greek sources learned how to use color and talea. In Baroque music, we have this extraordinary spiritual phenomenon, Johann Sebastian Bach, who somehow was aware of the primordial rules of construction. In the 20th century, this knowledge has again been honoured by the twelve-tone techniques of the Viennese School, notably in the revival of isorhythms in Anton Webern’s works. Webern wrote a thesis on the subject of Heinrich Isaac’s Choralis Constantinus, and he studied Isaac’s technique of melodic and harmonic development. I learned a little about the subject during my studies in Paris with Olivier Messiaen.

Messiaen accomplished a synthesis. He studied Indian rhythm and melody and related them to the Gregorian use of neumes (which also connect duration, intensity and pitch). Because Messiaen was a church musician, he referred his students again and again to the theory of neumes, and he used it himself as a composer. In Cologne I had already studied musicology and therefore knew something about the transcription of neumes into modern notation. So, there again was a connection with the primeval tradition of creating form based on archetypes. Though he later repeatedly maintained that it was unintentional, Messiaen was the first to approach a synthesis of Indian music, Gregorian music, medieval isorhythms and the serial music of the early 20th-century Viennese School. For my generation, the vision of such a synthesis was an explosive confrontation, and we have brought it to bear on every parameter of music.

In 1953 following my studies in Paris I started work in the Electronic Music Studio of the West German Radio. At the same time, I studied communications theory at the University of Bonn, as well as linguistics including phonetics and phonology. Linguistics is fascinating, but I was not specifically interested in the theory of languages; rather, I was fascinated by phonetics and acoustics, notably the analysis and notation of phonetic phenomena. At that time, Professor Meyer-Eppler taught communications theory and phonetics in Bonn, and through him I became familiar with modern techniques: statistics, chance operations, aleatoric, and the incipient digital theory. I subsequently applied the conceptual apparatus of these disciplines to music, so that I became chiefly responsible for the introduction of terms like ‘parameter’, ‘serial’, ‘aleatoric’ into German musical vocabulary, terms later adopted by the French.

Some of my first articles from 1953-1954 were published by French periodicals, and they contained the various new concepts that arose from my studies of information theory, phonetics, acoustics and communications theory. At the Music Conservatory (Musikhochschule) in Cologne I received a pathetically poor education in acoustics from Professor Mies who taught us a bunch of confused nonsense about pendulums and the like in order to explain tone frequencies. Actually, nobody really understood the nature of acoustics. Through my work in the Electronic Music Studio, I eventually learned the empirical and theoretical bases for acoustics, specifically electro-acoustics. I also contributed to the development of the field, an ongoing project.

Consequently, after 1951 music was moved to a completely new level. In this phase, technology and music, acoustics and musical composition, co-existed within the same arena.

AB: Since 1951, then…

KS: A completely new level existed compared with the entire tradition that had preceded it. The break with tradition (Zeitschnitt) was a result of developments in electronics and the new techniques for storing unlimited amounts of information relative to perception. This started a new technological and cultural era.

AB: Your LICHT Project seems to be comparable to Wagner in so far as his work expresses an ambition to encompass the past, the present and the future, as well as criticism and visions, art and religion. Does your great heptalogy also end with a Götterdämmerung, or are you, unlike to Wagner, a cultural optimist?

KS: I have to counter that with another question: what vision of the future is there to be found in Wagner?

AB: It’s a fact that his work has been interpreted as possibly indicating ideas about the future.

KS: In what ways?

AB: Well, it possibly points, to a certain degree, toward a new dimension by the force of its giant scope.

KS: No, I mean, what future does his work promise? Does it actually point towards a new future?

AB: Some interpreters have emphasized that the Götterdämmerung does not exclude the emergence of a renewed world.

KS: Really?

AB: Yes.

KS: Where is that indicated?

AB: Well, by musicologists and . . .

KS: No, what I am asking is, where in Wagner’s work is there such a reference to the future, in the music and in the text? Where?

AB: Well, it would be at the end, the finishing part of the work.

KS: What I want to know is, whether Wagner in his work establishes any connection to the future?

AB: That I don’t know.

KS: But that’s what you just said. You said: ‘Wagner’s work expresses an ambition to encompass the past, the present and the future’. What future, then?

AB: I was referring to people who have said that the work is not necessarily the end of everything but could open to something new. I don’t know how concrete you want it, but . . .

KS: I would like to know concretely whether or not Wagner’s work contains any kind of vision of the future.

AB: You find nothing like . . . ?

KS: No. I have always had the impression that his work is exclusively retrospective, a last review of a Germanic ideology, a Germanic world view. Something like a summary or a sentimental return.

AB: That would then be the difference between yourself and Wagner?

KS: I think so, yes. My work is not at all concerned with the past but is based on the idea that the protagonists represent a theory of evolution, a will for evolution. LUCIFER represents a static concept of the cosmos according to which spirit and perfection are forever immanently present. Contrary to MICHAEL, he needs no evolution, since evolution is tied to imperfection, and to the effort to achieve perfection. MICHAEL’s view entails misery; it means suffering and death. The LUCIFER of my work LICHT wants none of that.

So, essential principles are at stake. The protagonists are not historical figures, but instead, I insist that whenever my work LICHT is performed, these two spiritual forces manifest as timeless, immanent cosmic spirits: MICHAEL as creator in our local universe and the one who inspires all developmental processes, and LUCIFER as the antagonist who opposes the uniting will of the cosmos. LUCIFER is the no-sayer, whose message is: ‘There is no single and unifying will-power or unifying spirit. God is a phantom, and I am just as important as he’. That is LUCIFER’s rebellion.

Then there is the third principle in LICHT, EVA. She is the feminine principle in the cosmos, always endeavouring to mediate, in order to beautify and perfect all living beings. She is responsible for new life on the planets. She wants to enable mankind to have more musical and more beautiful children, Sunday-children. That’s EVA’s mission, and for that reason she always tries to reconcile MICHAEL and LUCIFER. She is enthusiastic and very hopeful.

In this regard it is true that my work is not only concerned with our times; rather, the protagonists are timeless, ever-present. They inspire us, they are the great spiritual forces that motivate us, the guiding principles. They will be present for all the future, just as they existed throughout the past. I assume that this concept is unrelated to any specific epoch in the life of this planet – contrary to Wagner – or to any partial solution or conclusion. What interests me is the outlook, the futuristic dimension and the question, what does this concept contribute to the future development of mankind?

This is also true of the music. Every small scene, every detail, that comes to me day by day, is based on the formula, which is the unifying principle, the skeleton of the whole. I need an uncannily large number of inspired ideas and loads of intuition regarding details to make sure that all these details become integrated in the large genetic process of the work; in that way the larger organism is enriched and keeps growing.

AB: Wagner uses the Leitmotif technique to bind his musical and intellectual universe together. Does your formula approach a comparable principle?

KS: As far as I know, the Leitmotifs are like traffic signals that announce what kind of character is arriving, like signs that say, ‘Attention’! In the formula technique for LICHT, the super formula (Superformel) is the code for the entire work. Nothing falls outside the formula: The large form, which is a projection of the formula over a long period, and the smaller forms, which reach into the tiniest structures are either expansions or compressions, which stretch or condense the formula, or they are superimpositions, mirrorings and transformations of the formula. It is largely comparable with a genetically coded organism, in which the multiplication of cells leads to the growth of a complete body. Everything is derived from the formula, and there is a radical difference between the use of intermittent signals to announce the arrival of a character and the use of a single germ to develop a great organism with all its various figures and shapes.

AB: True. Talking about the formula, I’d like to read you a relevant comment on this line of thought in an essay by the American composer, Morton Feldman, who says “. . . the artist has an incredible problem. Especially if they are young and they are growing up because everything is right. Bach is right and his Kinder are right. Gluck is right, Palestrina is right, Karlheinz [Stockhausen] is right, everybody is right. The confusion of a young artist growing up is not the confusion that everybody is wrong and I’m right, the confusion is that everybody is right, am I wrong? So, you’re intimidated, because every system works, because they set it up that it does work, and it’s the nature of western men to do fantastic things, and so it works. Hegel works, Kierkegaard works. Kierkegaard said, “It doesn’t make any difference, because eventually what is gonna happen to me is that I will be part of his system, he is gonna incorporate me in his system”. So, if he doesn’t work alone, you see. And then someone else incorporates, this is the formula of Stockhausen, and it is based on a military formula. And the military formula is this: “You make a small circle to exclude me, I’ll make a larger circle to include you”. And essentially, this is a dynamic in history. And then after 300 years we look at it, we refine it and we start all over again.”1

What would be your response to this?

KS: What is the problem? I think it is stupid to claim this has anything to do with the military, because the military is part of an overriding cosmic force that, for instance, gives coherence to solar systems. It is pointless to get all upset because our solar system does not include all the planets of the universe; that is what other solar systems are for. I fail to see that it is problematic for a young composer to develop his own world. He is free to do that. Like Gluck . . . . That’s fine. Why make a problem out of the fact that one is afraid of others? Anyone who has the desire and the gift to do so should build his own world; it can only be a source of fascination to others. It is so much more interesting to build one’s own world than to want one world in common. I certainly don’t want to see everything being the same. On the contrary, I want to realize only my music.

AB: Pursuant to our discussion about Wagner, it seems clear that Adorno was not exactly optimistic in his view of culture. He and Jürgen Habermas promoted a certain branch of philosophical history that sees modernism as an unfinished project. Adorno maintains that ‘the new’ is an important categorical designation, and taking Schoenberg as his chief witness he establishes that negativity is essential in defining moments of truth. Key terms are, ‘historic necessity’ and ‘the objective tendency of the material’. Today we are inclined to question this school’s belief in an ‘historic necessity’, and rather see this faith in the coercive force of history as a compulsive obsession. Still, these responses to modernism remain focal in debates and function as a counterweight to the postmodern vision of abolishing the concept of an ‘historic’ time frame. You knew Adorno and discussed his Philosophy of New Music with him and your own music has been interpreted in the context of the philosophy of history that Adorno put forth. But to what extent do you recognize yourself in his philosophic construction? Have you been able to actually make use of his ideas in your compositions?

KS: I met Adorno a number of times. On one interesting occasion we were sitting in the Schlosskeller in Darmstadt late one evening after a day full of seminars and concerts, and he said: ‘Stockhausen, I am really a musician, a composer’. One of his students sitting next to him (Andreas Razumovsky, a music critic, if I remember rightly) commented: ‘But Teddy, you are really a philosopher’! Adorno replied: ‘That’s unfortunately what I always hear, but truly, I am first and foremost a musician, a composer’.

Now, some of his songs had been performed at the Summer Courses, and they revealed that he was not a very original composer. He always wanted to pass himself off as a pupil of Alban Berg, because Schoenberg had refused to take him as a student. Adorno’s problem is characteristic of many intellectuals in the field of music who are devoted music lovers. They always long to be composers of original works, just as the great masters of the past wrote original works. But deep down they realize that they lack the wealth of talent and the mark of genius needed to become original composers. But this longing find expression in their theories. In particular, such people are enormously negative towards other composers whom they want to sweep aside by the sheer power of their intellects. Adorno was like that, and he made dreadfully mean comments about many composers. Even the world-famous Stravinsky was included in the list, not to mention people like Orff, Egk or Blacher whom he totally annihilated. The only one who was accepted as a representative for new music was Arnold Schoenberg.

Adorno was strongly attracted to my works. He attended several performances and he noticed that they reflect a strong belief in the necessity to discover something new wherever feasible. It is not a simple matter to discover something really new; the process is closely linked to technical evolution. It would not have been possible for me to make so many new discoveries without the development in electronics, the new technology in performance practice and without the general interest in innovation: the exploration of outer space that began around that time, astrophysics, nuclear research, new trends in biology, the development of artificial materials. Since 1950, there has been a veritable explosion in all these fields, and it continues. Every day the electro-acoustic industry puts out new equipment. There is no end to it, and it is accelerating. There is no stopping it.

In music, this takes on a particular significance just as Adorno’s role takes on significance, because – though a mediocre composer – he argued that the permanent revolution caused by technological discoveries also affects musical performance techniques. To me, that is particularly important in the context of electronics and all the related studio equipment and performance practice. Driven by its own internal dynamics, this force is, as Adorno realized, a reality, whether a composer goes along with it or not.

The thing is, there are still many composers who continue to write one symphony after another, oblivious of the innovations of the 20th century and the opening up of radically new techniques. They are once again writing series of string quartets, they follow the traditional patterns for orchestral scoring, write their solo concerti, their little operas and Lieder, their orchestra works in four movements, and so on. You’ll notice this expressly reactionary tendency everywhere, and it currently calls itself postmodern. It’s a truly revolting term, for there is no such thing as modern, postmodern, or for that sake, premodern. For a creative individual, every day is given to new discoveries, new questions and new inventions.

Any person who is obsessed with becoming famous in his field but finds out that he lacks talent, will respond by an attempt to develop his own system; this is also true of musicians. But if his circle is too narrow, as Morton Feldman expresses it, and he becomes afraid of the larger circle which threatens to absorb him, then he becomes angry and starts attacking other composers. Europe is rich in mediocre or incapable people with huge egos. Here, at the end of the 20th century, because all generally accepted criteria of quality have dissolved, there are plenty of opportunities for such people.

‘Inherent historic evolution’ is a reality, no matter whether a Stravinsky or an Orff or a Stockhausen goes along with it. Music has its own dynamic. Just like physics, which again is not dependent on the contribution of some physical scientist in, say, Munich. Daily, something new is revealed within physics, space research, astronomy; every day brings new discoveries. Some astronomer in California may pass away, but another will surely notice the next supernova or discover a wholly new region of the universe.

You must acknowledge this inherent evolution and realize that music is not a separate entity but one of the spiritual realms, besides being one of the natural sciences, namely the science of acoustics. Within the scientific study of acoustics, new discoveries are made every day, and it is up to composers whether they make use of these innovations or not. Most of the interesting experiments nowadays are made by pop musicians who are not composers but ‘transformers’. They pick up whatever comes along, load it into their samplers – also into their mental samplers – and they blend it in their brains as well as in their computers, until they have a mix that somehow sounds ultra-modern. When that mix is projected through modern equipment, it often sounds rather interesting. These pop musicians are not afraid of modern techniques. They simply take everything that the industry has to offer by way of modern technology and make something different of it, something new. And that’s perfectly fine.

No matter what area you are in, you can’t possibly carry on as a productive individual, not even for one more day, unless you firmly believe that tomorrow will bring something interesting, not just more of the same. This results in total confusion among musicians because they are scared at the very thought of being modern, since they assume that nothing remains to be invented and discovered. That’s a tremendous mistake.

Morton Feldman was, actually, a poor guy. I met him several times and we got along with each other very well. His problem was his eyes. He wore glasses that were almost half an inch thick. On top of that he was an alcoholic and a great gourmand. He loved eating more than composing. Once in a while, his poor eyesight forced him to draw notes the size of eggs on a sheet of paper stuck to the wall. He quite simply couldn’t draw anything very complex; tones had to come two seconds apart or more, otherwise he would never have finished a piece. So, he made a virtue of necessity. But he was an intellectual and wanted above all else to become famous, and so he used his intellectual resources to denounce others. He was what he was: That’s that! Morton Feldman: ‘as slow as possible’ and ‘as soft as possible’. That is about all. But it constitutes a kind of private style, as in the case of the painter Yves Klein, who one day decided to paint only blue pictures. He became famous for his blue pictures, blue objects and blue happenings. One may paint only squares, like Josef Albers, or only write ‘as slow as possible’, like Morton Feldman. That’s the way of ‘style-composers’. They look for some very narrow, tiny little circles that circumscribe their self-identities and allow others to recognize them. That is the stuff polemics and congresses are made of. There has to be some theory too, and some philosophical statements about the ‘circle of the nothing’, the ‘border of silence’, or the ‘void of muteness’.

Gone are the days when a composer was expected to produce a rich variety of original works, to be a master craftsman for all kinds of instrumentariums, to boil over with inventive ideas, instead of variations. But shouldn’t a composer create models that could help others assimilate new developments in the areas of form, harmony, rhythm, dynamics, coloration, topology? Should he not demonstrate how it’s possible to balance logical development against surprising ideas, or to pit the intimacy of calmness against youthful stormy temperament? Do we no longer expect a composer to create a rich, diversified work that confronts a variety of challenges for the benefit of not only the musical life of his own nation or continent, but of the whole planet?

AB: It is hard for people in the Nordic countries to comprehend the influence of Adorno in the 1950s. We read his texts, but they do not explain all . . .

KS: Hmm.

AB: Am I right in believing that he was crucial to the understanding of the necessity for constant renewal of musical material and so forth? Did you experience that in the 1950s?

KS: Indeed! From 1947 to 1951 I studied musicology as a subsidiary subject at the University of Cologne, but I took time to read thoroughly Adorno’s Philosophy of New Music and to give a lecture on it at the Musicological Institute. I also took part in discussions of the book. You know, the language is extremely complicated, and one needs to analyse critically what he is actually saying. One provocation presented by Adorno’s book – the one that made it famous – was obviously that he took the then current consensus about the world-famous Stravinsky and the not-so-famous Schoenberg and turned it around: “Look at Schoenberg! Stravinsky is really just an overrated folk-musician who writes entertainment music.” That was about the extent of his thesis.