An interview with Olav Anton Thommessen

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: Let’s look back through history in order to understand the development of recent Norwegian music. You once said that national romanticism had been unduly prolonged in Norway and that many famous Norwegian cultural personalities—Hamsun and others—had sympathized with national socialist movements in Southern Europe. What’s your view on the cultural legacy in Norway?

Olav Anton Thommessen: That is still a rather controversial subject and it has not been spoken about explicitly enough. Recently in Iceland the film about Jón Leifs, Tårer af sten (Tears of Stone), really put that period in perspective. (Leifs was embroiled in national socialist ideology, ed.) To do something like that with the Norwegian composers of the time would be very difficult, not least because the relatives of those involved are still living. A number of festering conflicts remain. Many wounds are not yet healed.

No one has told me what actually happened. I have had to put the pieces together and make my own interpretation of the details. But it is clear that Norwegian national romanticism went through a very negative development from the time of Norway’s independence and liberation (1905) through the 1940s, when nationalistic sentiments continued to prevail and ideas from Italian fascism and Mussolini gained a foothold in Norway. They had slogans like ‘You have to fend for yourself’, and ‘You must purify the national identity’, which I believe greatly affected the arts for better or for worse. Think, for example, of the painter Gerhard Munthe, of buildings with medieval-style carvings on them and of everything that was cultivated as something pure and Nordic.

Folk music continued to be idealized and some composers continued to gnaw on Grieg’s quasi-folklorism—I find the whole thing completely incomprehensible. Composers travelled to France and picked up a few ideas there, or they travelled to Germany and learned some new techniques, but on the whole most of the composers used nationalistic material. The only composer really to break with this trend was Fartein Valen. Valen was born in Madagascar so the Nordic ‘tone’ was not actually very relevant to him. In many ways I feel a certain kinship with him. I was born in Norway, but I didn’t grow up there and even though these Nordic folk melodies are truly charming, they aren’t something I am passionate about.

Valen represented something extraordinarily interesting in Norwegian music. He wasn’t well received: he represented European culture in the broadest sense and practised a form of neoclassical expressionism. This is a direction that no-one else at the time represented in Norway. He came home with a host of ideas that were completely foreign to everyone. If David Monrad Johansen was influenced by French impressionism, or Pauline Hall by neo-classicism, it was on a very superficial and half-hearted level. Valen represented a true internationalism. He was also such a weird person that he was later marginalized and treated like some odd apparition. If there had been a responsive system capable of absorbing him in Norway, its art music would surely have gone in another direction.

Unfortunately, because many people still fostered nationalistic views, some of the artists were led to support the wrong side. The artists who truly had something of an international character in them—Geirr Tveitt, David Monrad Johansen and Olav Kielland—became in some way non-persons after the war. They were shunned, and an amateurish generation of self-taught composers came out of the woods to take their place. Professionalism was viewed suspiciously because it had led us into Nazism. For that reason the specialists, those who truly knew something, received no particular recognition. Instead, attention was focused on another type of artist, one considerably less sophisticated, who was, by and large, self-taught and as such unlikely to be contaminated by such international depravity as Nazism.

We have had to struggle with this prejudice ever since. Expertise became discredited because so many experts had become Nazis. It has taken a long time to rebuild the understanding that a certain amount of expertise is actually desirable and far preferable to reinventing the wheel time and again, as some of those homespun artists did.

After the war, there was a precipitous lowering of standards in Norwegian composition. A main reason was that there was nowhere to study composition in the country. You can understand why such a naïve person as Geirr Tveitt became attracted to Nazism: the Nazis planned to build an opera house and conservatories and gave priority to higher education. We still don’t have an opera house. The Music High School was only built in 1973 and instruction in composition didn’t start until 1980—that is, in the form of a complete course of study and not just a diploma exam. So it has taken its time. Some of the artists who became Nazis may have seen a so-called new era as the possibility for professional advancement. However, when they were discredited, there arose an even better argument for putting off the establishment of the Music High School, the opera and the concert hall—it was fashionable to do without it.

AB: Let’s skip ahead and consider those Norwegian composers who recently resigned from the Composer’s Union in protest against the new avant-garde. I heard a premiere of a work in Trondheim that was so romantic, it could have been composed in the last century. So the situation that you have described still exists in Norway. I don’t see anything like that in either Sweden or Denmark. A branch of Norwegian composers is still devoted to pure and unspoiled—I nearly said uncontaminated—lyricism.

OAT: In the Composer’s Union there is a small group that is marked by loyalty to such ideals. They are very unappreciated because their aesthetic position is not acknowledged and they embrace an aesthetic that had its day a long time ago. I don’t actually know why they compose, since they continue to live with this artistic myth. Most Norwegian composers are interested in current ideas, not least because of the programme at the Music High School and the establishment of NoTam, a new centre for electro-acoustic music. Consequently, most composers are orientated toward today’s music, but there is still this little pocket of dissatisfied people who sit and feel that they are being treated unfairly.

A stabilizing factor

AB: But in your case, you say that because you moved around with your parents you were suddenly put into situations where you had to deal with many new directions. You once used ‘Auschwitz’—a powerful word—to describe the various atmospheres of the many boarding schools in which you were enrolled during your turbulent life and the changing circumstances you experienced. Can you describe your upbringing?

OAT: If one looks at the children of diplomats as a group, there aren’t many who have been successful. Diplomacy is not a particularly child-friendly occupation. On the other hand the children of diplomats have a fantastic opportunity to experience a great number of things. In my case, I had a very active ‘inner’ life, for the stable ingredient has been music. From the outside, my life must have looked like that of a vagabond. I have gone around and thought—almost half-acoustically—about musical ideas without letting myself be influenced by external changes and this became a way of surviving my itinerant upbringing. But it has also been very positive, because these days I maintain an active inner life.

AB: When did you settle down in Norway after roaming the earth?

OAT: In 1969. I took an advanced course in pedagogy in order to be able to teach in Norway. That’s how I got into the milieu of the music conservatory in Oslo. Subsequently I was granted permission to teach instrumentation—I took over from Trygve Lindeman. I was also allowed to teach a bit of music education. In addition I travelled to Utrecht and studied sonology there. The funny thing is that my education didn’t match the Norwegian curriculum because I had studied composition in America, and they said I was ‘overqualified’ for many jobs. So the year after my study in Utrecht, when I applied for the position of teaching theory at the newly established Music High School, I got the job.

AB: In Utrecht and in the USA you had several defining experiences. You met Iannis Xenakis at Indiana University in Bloomington.

OAT: It was a very unsettled time with the student resistance to the Vietnam War, and so on. At the height of all that, it was the students who had to decide everything—we actually need a bit more of that today. We discussed who the composition teachers should be. We talked about Castiglioni and Xenakis. One group opposed Xenakis because the members thought his mathematics was pure charlatanism. Xenakis didn’t arrive at the ‘truth’, rather he arrived at solutions that worked for him and inspired him. He said that a glissando is a straight line—which in fact it isn’t actually—but for him, it is. And if one builds up one’s own system in that way, isn’t it a kind of ‘truth’? But a number of students said that Xenakis wasn’t being consistent. After a number of tug-of-wars, Xenakis arrived. These two years were extremely invigorating. He built up the electro-acoustic music program and the computer centre and began developing his interest in UPIC. He laid out his research during the lectures. His productivity was impressive; during that period, he composed Nomos Alpha, Eonta, Nuits and other important works.

Xenakis was really in top form and delivered some fantastic lectures that were inspirational. In addition to that he introduced to us the world around Varèse. This was quite new to me, because everything was very orientated toward Germany, with Hindemith and Schoenberg as central figures. So here comes Xenakis suddenly and talks about the French world of music, which was extremely interesting and completely unknown in mid-western America. Although Varèse was an American he was actually quite unknown at that time. He had died by then, but his music suddenly received a huge amount of attention. Coincidentally Bernstein was beginning to explore Mahler and The Beatles were extremely active. It was a truly exciting time to be a student.

AB: You have been called ‘the biggest compromise in Norwegian music’. Is that—looking at it positively—an expression of the pluralism that is also part of your music?

OAT: I believe that was a printer’s error—or rather, it was a printer’s error. It’s not far from ‘compromise’ to ‘composer’ in Norwegian. But it is a kind of Freudian slip. There is something to it, but they got it wrong. There was an article in Dagbladet the other day, where it said that I was an advocate of pure music because I had said that I couldn’t stand Chick Corea’s interpretation of Mozart. I had pointed out that Corea purely and simply cannot play Mozart, but suddenly I was guilty of insisting that my Mozart be pure. The journalist was all in favour of impurity in music, but he can hardly have heard my music because you can barely get more impure music than mine. ‘Compromise’? I have heard an awful lot of music and there are some types of music that I don’t like. For pure stylistic reasons I don’t like country music, and I have difficulty with jazz if it’s not inspired. These are the only two styles I have any problems with, otherwise I think all music has something to offer. The other day I heard a Korean opera from the 1300s. I have never heard anything like it before. You discover things all the time that you would never dream someone could have invented. There is always something that you haven’t heard. I really like to listen to music.

Sonology

AB: Your willingness to listen is evidence of your pluralistic approach to music: your positive words about Valen and Xenakis; your activities in the school as a professor, where you don’t miss an opportunity to travel with your students to the premiere of a Stockhausen opera; your ravenous appetite for film music, etc., etc. How is it that your interest in listening to so many different kinds of music hasn’t influenced your own way of thinking about music? What about the pluralism mirrored in your work when you recycle music history?

OAT: Together with Lasse Thoresen and others, I worked in an improvisation group called Symfrones. We were greatly inspired by Stockhausen when he came to Oslo in 1969 with his group and improvised freely—Kagel, the Kontarsky brothers and Eötvös—that was a star-studded group. They sat on the floor and messed around; it was really ‘modern’ and they made all kinds of sounds. So we thought that we had to try it as well and we began to play together. That way we got a kind of understanding of what music is without defining stylistic criteria and without the constraints of having to play in a specific style.

Thoresen and I gradually discovered a hidden world lying beneath all the styles of music: the real force that makes music acquire the form it has, the sound it is composed of, and the way these sounds function within the whole. As a starting point, we began to work with the theory of sonology, which has been extremely useful for us as a pedagogical tool. It has been well received at the Music High School because many performers have found it useful in deciding the difference between one interpretation and another. It is, after all, useful in comparative musicology. One compares different kinds of styles and finds common tendencies at a deep level—not on a superficial one, but actually on the level of musical impact. We have spent a great deal of time on this and it is one result of this pluralism that you speak of. We attempted to determine comparative criteria. You begin to discover that there is actually something astonishingly stable in music. It has to do with clarity and with the ability to discover the means to formulate things as perceived by the listener.

AB: This was the same time that scholars working in linguistics began to explore …

OAT: Semiotics . . . and also the thing with Chomsky’s ‘generative grammar’. We lived through a very exciting time in linguistic research. We found that we could possibly construct an auditive music theory from the principles of the language theories that Saussure developed in 1911. But we were also interested in what the structuralists had done in light of Levi-Strauss’ socio-cultural research that identified connections between cultures.

We were inspired to think about whether we could do the same thing in music. For years we tried to publish a book about what we discovered, but it’s not so easy—we still work with those old stencils. Perhaps we will get it published someday. It is really strange that our thoughts can’t be printed, since it’s original research—speculative possibly—but it is original and therefore, perhaps, it isn’t taken seriously because that’s not what the research community is interested in. They would rather take something that is already known and simply shuffle it around. Here we come with something that is completely innovative, but it turns out that it is difficult to get sonology recognized as proper research. It is a tool for discussing music for performers and composers, and is based on what the listener perceives.

AB: Many musicologists have an opinion about both semiotics and sonology. One group is sceptical about the possibility of sonology as a science, possibly because the critics are not adequately informed. Who knows? Is it possible to say briefly what sonology is about? Is it a kind of hermeneutic method that can be used to discover what music is about?

OAT: Yes, but to say ‘is about’ is a bit too strong; it’s wrong to imply that it is possible to know what music ‘is about’. But it is possible to know what functions music has—that is relevant. Rameau discovered something very important, namely that a sound could have a function on the strength of the three chords that he put down. Rameau had great insight—the idea of functional harmony—that is, giving a sound a function. But no-one had taken this idea further. We have tried to do that, and to say that there have to be more functions than just three—tonic, subdominant and dominant—and that there have to be more sounds in music that can provide these functions. At this point we start to look at how music plays itself out in time. It is tremendously important to have criteria and concepts that can describe music as an art that takes place in time. There is very little in traditional theory teaching that tells us anything about time; it tells us a certain amount about the elements but not about musical time itself.

It has taken Thoresen and me a long while to describe musical time. We have discovered that superimposed layers of time exist simultaneously. There are at least four layers that go at different speeds. And here we begin to talk about speeds in music. We discovered that sonology can often be compared to Adam in the Garden of Paradise. He simply went around and named things, ‘tree’, ‘bird’, ‘sand’. We have only put words on these functions, so we can hold on to them and they don’t just escape. That’s what sonology is: a tool for trying to describe music without using personal reactions such as, ‘It sounds like an insane murderer loose in the woods’—or that kind of fantasy.

We base our theory on something we call ‘intersubjectivity’, which is the kind of subjectivity that we share that is interesting; it’s not pure objectivity. Music theory has possibly been too objective. On the other hand it can get too subjective if we can make do with saying ‘It sounds like an insane murderer in the woods’. You can’t work with that kind of description of music. But if you discover criteria that are common to everyone’s experience, then you can work with such a description. For example, if you have repetition—we call them ‘fields’—for instance, a strophe, there are certain things that are repeated periodically. Then when this field is closed, something new begins and you have something that you can describe. That is what we have tried to do: make a description of sounding music.

AB: Can it be said that this is a modern ‘doctrine of affections’?

OAT: No, because it has nothing to do with feelings, it deals only with describing effects. The effects can inspire any kind of emotion; you may say music that sounds happy uses a particular selection of these effects extensively. However, we don’t go that far because our theory is not generative: it is exclusively descriptive and analytic. You can’t compose with the help of this theory, it is only on the pre-compositional level that the theory can help to organize one’s thoughts. It is an auditive-analytic system. This is very important because when I talk to a student, I can pinpoint the specific dimension in the sound image that the student is in the process of constructing. Furthermore, I can see how the student is in the process of developing this dimension and how it will eventually work when it is performed. We use the method as a kind of common reference that helps us to talk to each other about our work.

AB: Are you in touch with research that is going on in Utrecht?

OAT: We were, but we aren’t any longer. We have had a lot of contact with GRM in

Paris, but that is also completely finished. At one time we also had a great deal of contact with England and the research that was going on there. But now it looks very much as though John Paynter’s great pioneering work in the schools has fallen apart. At this point we don’t have much contact with other places, but we continue with our work. We have a new kind of student who is more interested in the constructive side of music. That is to say, not the affective side that used to be the focus of interest. So new students are working up ideas about music that remind me of the over-constructed music of the 1950s we rebelled against. Such is life.

AB: Do you also use sonology to expose the structure of your own music?

OAT: Of course. Sonology is a tool that can be used to analyse all types of composition; that is the best thing about it. Lasse Thoresen has been able to develop graphics to describe these phenomena in music—a kind of score for listening. We get students to make ‘listening scores’ out of the strangest pieces: from ethnic music and Afghanistan nose flutes to the most crazy electronic music. One student came in with a piece that was almost completely constructed from various components of noise. I thought it was a horrible composition, but his analysis of it was actually completely correct. It was an analysis of the sound image.

Indeed any kind of music can be analysed with this tool. It’s extremely useful. When you are through, you have a kind of score that you can begin to discuss; you can see how the form is created, and which elements create the form. We are very interested in form, which I think much new music lacks.

AB: In the 1960s Danish music reached a high point in pluralistic thinking. Music from all periods became a part of the matrix and was put to use. For some composers the problem of form became insurmountable. The Dane Karl Aage Rasmussen asked questions such as, how can you create form from heterogeneous material? How can one legitimate the fact that one tone follows another? How can we perceive musical development? How does one know when a piece is finished? The problem of form became overwhelming. In addition to that, music that incorporates music from earlier periods can also create form problems. You used Grieg’s Piano Concerto at the beginning of The Glassbead Game, the large-scale work that has the movement, ‘Through the Prism’, for which you won the Nordic Music Prize in 1990. Could you explain how you use existing works in your own compositions?

OAT: I have composed over 150 works and I think there are twelve that use pre-existing music. A great deal of my music does not use it. I have found that the choice of musical material is completely irrelevant. I think there is strong evidence that in the period of national romanticism too much weight was placed on the character of musical material. There had to be a pretty little song, a trumpet signal, or an ‘inspiration’. However, if you look at Beethoven (hums the beginning of the Fifth Symphony)—a classical example—there is nothing pretty there, no exciting material. Or if you look at Haydn’s symphonies the material is of minimal significance. What is interesting is what is done with that material. That is to say, what form it takes. This leads me to believe that you may use anything you want in a work. You may take a work by Grieg or any other piece as the basis, as raw material.

It is important to understand that music originates in something other than in inventing a melodic theme or tune. Wagner’s material isn’t spectacular (sings Siegfried’s motive from the Ring). That motive isn’t the world’s most enchanting idea, and in any case, there is nothing in the sound itself that indicates it represents a sword. The art of composing takes place on another level. I have come to believe it is equally valid to use one thing as another. There are a lot of devices and ideas that you can extract from extant material and use in your own way.

I also like to find the relationship between the musical material and the form. The more one meditates over the raw materials of a work, the more the form tends to emerge from the material itself. You discover that it is like a kind of Chinese box, and that the overarching present form is in the original material.

It’s great fun to write large-scale pieces; too much is lost when concerts of contemporary music consist of ten-minute pieces here and five-minute pieces there. One of the consequences of writing longer works is, however, that they are performed only once. The Cello Concerto, Gjennom Prisme (Through the Prism) has as yet never been performed at a concert. It has never been played! Think of that. The piece is sixteen years old, it is nine years since it received the Nordic Council Music Prize, and it has never been performed at a concert. Concert managers are terrified by big works. I have circumvented the problem by writing a large-scale piece in ‘chapters’—that is, in sections—but some of these sections are so long that they have only been played once. That’s the problem with being interested in form; the result is large works. It isn’t so much Grieg’s small miniature forms that I find interesting; it’s the big ones.

AB: Your thoughts on large-scale form are along the lines of both Wagner and Stockhausen. You aim to achieve a physical effect from sound and instruments and you are very sceptical about ‘cyberspace’ and have been negative about computer music.

OAT: Yes, I am very involved with live music. I think that it still has its place, but it is clear that the sound of an orchestra can be translated very well into cyberspace. I am completely aware of that. The sound of an orchestra has a fantastic quality that has taken generations to develop. It matches our desire to listen and our ability to discern sounds. The orchestra comes out fine on loudspeakers with amplification . . . I don’t have a problem working with that kind of sound. But what’s happening today? One goes to a concert in order to experience what one has experienced before. I think that’s a pity, because you can actually gain the same thing by listening to a record.

AB: Wouldn’t a large-scale opera be a better framework for your ideas?

OAT: I have composed three operas, but they are chamber operas. You don’t get a chance to make something big. I’m not going to bother working for years on something that isn’t going to be played. I could just as well sit and glare at the TV. You have to be realistic about these things.

AB: Don’t you have a decent opera house in Norway?

OAT: No, we don’t have an opera house—we don’t even have a place for chamber opera. So there’s a huge problem on a purely physical level. We have musicians who can play new music. Jón Leifs in Iceland composed such huge pieces that it nearly took the entire population of Iceland to play them. That approach to composition is completely unrealistic. We have the musicians in Norway and we have the orchestras, but we don’t have the spaces. It is so ridiculous. It took us a long time to get the Music High School, and as soon as we started the school attracted 500 students, and now it is too small. It is quite absurd, but that’s the way it is. What we lack in Norway is a cultural ‘infra-structure’.

Film music

AB: It’s evident that you are deeply fascinated with some quite special topics. Why are you so fascinated with film music?

OAT: The medium of film has given composers the possibility of creating a completely new art music that is different from all its predecessors. Historically many late romantic features and futuristic features were extended in film music. It is still borne of European culture because it was predominantly created by Europeans living in America—and, to a lesser extent, those living in Europe of course. It is laughable for anyone to say that orchestral music ended in 1911, because it has clearly continued in film scores as a late-romantic and futuristic orchestral music. It’s actually alive today. At the moment, I am listening to the music for The Insurrection by Jerry Goldsmith, which is enormously exciting. There are very few concert composers who write such interesting music. I would much rather listen to something like this than to another pretentious reactionary Norwegian composer with his latest soul-searching song.

They say that film music is fundamentally dishonest because it is about something that was not experienced by the composer. On the contrary, I think that it is honest music because the composer has not mixed his feelings into it; it is completely objective. As a result the work can be concerned with technique and composition.

A film music score may sometimes have three movements that are completely engrossing to listen to, and good enough to be heard in a concert hall. Instead, we hear yet another performance of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. I think that it would be infinitely more interesting for the public to hear the music of Franz Waxman for The Bride of Frankenstein, the Creation of the Female Monster. It is an enormous piece. Or Jerry Goldsmith’s music for Supergirl where there is a movement that is called The Monster Tractor. It is a dazzlingly virtuoso orchestral piece, and very well composed. When dollar bills are dangled in front of the noses of the musicians, they play their hearts out. You won’t ever get contemporary music played like that in the concert hall. It’s the same with John Corigliano’s music for Altered States. This is really advanced contemporary music with many purely abstract devices, a lot of electronic expansions of all kinds. The music for Alien III by Elliot Goldenthal consists of orchestral pictures that are manifestly excellent. By studying these works one can learn how to develop instrumental music with the help of electronic make-up and all kinds of effects. This is possible because the producers work with big budgets.

There are always two or three films a year with remarkable music—much more interesting than most concert music. I think it is perverse that orchestras don’t think of performing this film music when they, at the same time, talk about how orchestras are in crisis and what have you. There is a wealth of exciting music out there, if you only care to get acquainted with it.

AB: There are also composers such as Takemitsu and Schnittke who understand how to use elements from one kind of music to enhance the other.

OAT: Yes, and they have learned something about working with both genres of music. Take, for example, Schnittke’s Second Cello Concerto based on the film, Agonia. It is a fabulously dramatic piece. I think this distinction between popular music and serious music is something that came about after the war. Before the war composers had a popular dialect in their style. They could absorb much more of the musical scene than composers do today. I think it’s important that a composer speaks in different styles in each work—in the same way that a speaker can address you in a casual, a didactic and an emotional manner.

Composers also made pleasing music in days gone by. Mozart did, Beethoven did, everyone did up until Schoenberg, who composed cabaret songs. This split is, in fact, something that has happened recently; you purify a position instead of being able to move with it. Right now I am writing a very flashy orchestral piece that lots of people will almost certainly think strange: music in casual dress. In a way that is also what is happening in Makrofantasien; it is speaking to the public in different ways.

AB: You have just used the word, dialect. Earlier you told me that what composers write today isn’t really new music, but dialects of a larger language family. This is a provocative idea because there is still the post-Darmstadt attitude that music should be absolutely new each time, or, in any case, there is a belief that it can be that way. But you don’t perceive music as something that should break with everything that has gone before, and consist of something previously unheard?

OAT: No, because a break is a kind of continuation. If you do the opposite of something then you are largely doing the same, because you would not have done the exact opposite if it had not been for what had come before. Consequently, it is a kind of continuation. There are very few instances in music history where one can find the beginning of a completely pure style. Gabrieli’s style was one. The early form of serialism that was heard for a very short time in Darmstadt was a completely pure style, that is, if you want to use the concepts of ‘pure’ and ‘impure’. It is very seldom that this happens in music history and it has happened perhaps on only one or two other occasions. But it isn’t anything one can count on when creating new music.

All this talk about a ‘new’ music—the idea that you should make a completely new kind of music—originated at the beginning of this century. There were several tactics for creating it: one was neo-classicism—the recall of order—where they went back and tried to draw conclusions about what music was, and hence what it could be. Composers drew some general conclusions and created a new style that reflected all the knowledge and experience that had been stored up in musical notation. Next, you have ‘the call to order’, the twelve-tone music: one invents a principle of order that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with how one listens, but has more to do with music as an intellectual process—a notated music consisting of mechanical variation. And then you have the third direction, where you venture behind the musical substance and try to make music that is an archetypal expression. This third direction is futurism. Take for example, Mosolov’s Iron Foundry, and that type of primitivism and cultic expression.

These three postulates emerged at the beginning of this century and they suffered different fates. The one that has survived is the serial mode of thought—the computer has suddenly given it a new lease of life. But there is also the archetypal mode of thought and it continues in film music: music as primal effect. That is a tradition that continues today, while neoclassicism has been seemingly tamed into post-modernism in which you merely rework the past from different angles.

AB: Let’s continue the focus on the sources of your inspiration. Wagner’s music fascinates you. Tell us about it.

OAT: Wagner accomplished an amount of work that is downright scary. You can talk about Jesus, but think what Wagner managed to create—in addition to designing a complete theatre with seats and everything. It’s a life’s work that is simply fantastic and he did all of that in less than seventy years. It says in the Bible that you should reach seventy years and then die; and that’s what he did! The instrumentation that took him so long to develop is outrageously interesting; that’s where impressionism has its roots. You can hear Debussy when you listen to the second part of the music for the Venusberg. It is pure Debussy in sonority—solo strings in octaves, with the most delicate flute lines. Wagner talked about the music of the future and his music, in fact, is this music. His sound is so commercial that it is pure movie-time; the scene of the rising sun in Götterdämmerung is pure and simple Hollywood. The end of The Ring is a Hollywood tear jerker. It is fabulously effective and competent, but he uses almost no material.

The Ring is an enormous variation in which Wagner launched a whole new way of composing. Wagner made the composing process more effective. This is one of the first mechanistic compositional processes that did not come from the Leipzig school. Wagner introduced a kind of variation technique that became the precedent for the twelve-tone system. The Ring is a genuine variation; these themes can be taken up and woven in wherever they are needed. It provides unbelievable insights into the nature of composition. It took Wagner a very long time to find his way—it is interesting to see how long it actually took. But bang! all of a sudden he realized what he could do to make the compositional process more effective. It is the obsession with automation that emerged at the start of this century. How much of a composition can be automated? I think Wagner found an incredibly interesting answer to that question.

AB: Let us go back to your early childhood, a period of your life that isn’t discussed very often. Could you talk about it?

OAT: I moved to New York when I was twelve years old and had composed music for as long as I could remember—it’s a lot easier to write music than it is to practise the piano. I made compositions that were variations of the music that I had to practise and technically a great deal easier than the pieces I was forced to practise. They were very much à la Grieg and all in A minor. When we arrived in New York my parents were introduced to Vera Zorina and her husband Goddard Lieberson who was the director of Columbia Records. His son Peter Lieberson has become quite a well-known composer in the USA. His father was really kind to me and said that he could help me get some instruction, so I began to study at The Mannes College of Music in New York. My teacher was Carl Schachter—who, himself, became a well-known theorist—and I studied composition with him. The work we did involved imitating various styles of music—I had to write minuets in the style of Haydn, and that sort of thing. It wasn’t the kind of composition instruction that I wanted or needed and when I returned to Norway to teach composition with some colleagues, imitating styles wasn’t part of what we did. However, that’s what composition meant for me as a twelve year-old in New York.

Later I took my portfolio to Indiana University in Bloomington. Bernhard Heiden looked at my helpless imitations and asked: ‘What are these neanderthal harmonies’? That was Bernhard Heiden who taught at Indiana University. My initial reaction was that I didn’t want to go to a school that rejected my efforts in that way, but later I appreciated his reaction. He taught me to compose in the style of Hindemith—a very liberal kind of teaching that I liked a lot. He taught general principles, and that suited me very well. However, I didn’t actually like Hindemith’s style; it wasn’t what I was after, so I didn’t get anything specific from the course that I could build on.

AB: It is interesting to hear that it wasn’t contemporary music that inspired you, but older music. I suppose that was due to your upbringing. Is it possible that you only truly heard contemporary music for the first time when Xenakis came to teach at Indiana University?

OAT: We had a couple of recordings of music by Arne Nordheim at the Consulate in New York. I think it was Canzona and Epitaffio, and I first heard them when I was about 14–15 years old. I thought they were really interesting but I didn’t know why—the music was so different from everything else I had ever heard. It remained lodged but unused in my brain. Indeed those pieces were inaccessible then and are so still for many people today. Listeners don’t know what the music is about, they don’t know the parameters. Because they have only clichés to rely on, it isn’t accessible. And that’s the problem, especially for young composers, because they risk becoming imitators of other people’s styles, or members of the conservative wing I spoke about earlier—the sort of people who compose trumpet fanfares, fugatos and such things. They are the ones who have not grasped the scope of contemporary music and find themselves too much submerged in obsolete technical aspects of composition. Then suddenly there comes a day when they are too old to change their styles and so they are stuck. I was lucky to go to the right school. It is actually vital which school one goes to because there are so many places where you don’t learn enough, and things can go terribly wrong.

AB: Let’s hear about your situation at the end of the 1960s, which is when you went to Indiana University. Your encounter with Xenakis and his ideas about music that is without emotion, was decisive for you, even though your music doesn’t sound like Xenakis’ at all.

OAT: His way of looking at music as acoustic architecture, simple and pure physical elements, sculptures that make their way through space, fascinated me. I think that that way of approaching composition is so amazingly physical—you can imagine that you are actually in a building, a three-dimensional space, and that music is the material from which the building is constructed. That was very close to the way that I experienced music. I experience Beethoven in that way, particularly his orchestral music—a very physical medium. Our emotions are fundamental; they concern our ability to respond, whether with sorrow or with joy. The ability to react has something to do with this basic source of emotions. Through our emotions we comprehend our existence as energy, pure and simple. Music is just this. I think of Xenakis’ music as pure acoustic energy. He is very clever at measuring precisely how much energy he needs to let out at any given moment.

Xenakis believes that mankind hasn’t developed since the time of Greek and Byzantine thought. It’s a ridiculously provocative stance to take, but there is something in it, for if you look at these systems of thought that he feels a part of, you can see that they are fundamental models. As far as I can tell he makes a kind of music that has never been heard before; it almost defines a new type of civilization. Xenakis imitates. He thinks about how Greek drama ‘really’ sounded and then he tries to make his own version of it. Xenakis sees the philosophers of that time as akin to the philosophers of today and he tries to build a bridge across the gap in time between them. He achieves this, in part, by looking at the formal side of things: mathematics. I am profoundly unmathematical; I cannot think in that way. But I can find my own way of adopting that kind of thought without being so formally rigid.

AB: Some composers have rejected their earlier works. They no longer recognize themselves in them and they choose not to speak about their juvenalia because it no longer represents what concerns them. How would you describe your style before and after your encounter with Xenakis?

OAT: I believe that Xenakis really taught me about polyphony. I had actually never really understood polyphony and simultaneity. That to say, you can work with a form of musical expression where several events take place at the same time, supplementing each other. Xenakis explained it to me like this—he said that a number of universes function simultaneously. You can experience a simultaneity that actually isn’t chaotic, rather like society itself, where a great number of things are happening at the same time which may or may not influence each other. He has introduced the notion of interpreting counterpoint as simultaneity in Western music: heterophony. There is very little Western music that really tries to investigate the nature of heterophony, and that is something that he has worked extensively with. These sound masses consist exclusively of heterophonic events. It’s incredibly interesting.

I have done nothing as impressive as Xenakis, but the idea of working with the elements of heterophonic sound, merging transitions and polyphony as simultaneous events, fascinates me too. I always compose all the structures in my music simultaneously. I don’t just write one layer and then the next; I write the whole thing at the same time, so that I have to hold all of the events in my head. It is a lot easier to make the first layer and then lay another one on top of it, but when you do as I do, you can make sure that they don’t contaminate each other, that they are always in complete polarity.

AB: Is that why you call yourself a ‘multi-tracked’ phenomenon?

OAT: That’s it. But it also has to do with the fact that when I compose I have to have lots of stimuli around me—three radios and a television turned on and also, if possible, someone I can chat with. Only then can I concentrate on all the layers. I’m Richard Strauss who composed at the kitchen table while his family streamed in and out. It is nice to have distracting things that function as stimulation. It can very easily get too overheated if you concentrate too much. When a composition is at its most complicated, it’s very demanding to hold all of one’s thoughts in check at all times, at least for me with my limited brain capacity. When the whole orchestral apparatus is activated, I find it incredibly complicated to ascertain where I am. You have to be able to see the layered relationships that emerge and to hear how they will actually sound so that you are not just working on a theoretical premise.

You also have to think about how to get one layer really to stand out. It’s a matter of instrumentation but you have to be careful to make sure that it really happens. It’s too simple just to say, ‘Here is one layer and here is the other’, without actually hearing anything. Per Nørgård showed me his Fourth Symphony and said to me, ‘Tango Jalousie is being played here’. One violin plays Tango Jalousie! It is an amusing idea, but I don’t think that anyone hears it. If Tango Jalousie is an important idea then the composer should probably ensure that it can be heard. People listen differently, but if you have an idea, it stands to reason that it should be heard. As I said, it is all a question of instrumentation. There are many composers who simply have an idea, and don’t assure that it’s audible. In Xenakis’ music you can hear everything that he has written. You can hear where it goes. Nothing is lost—nothing. If something disappears, it disappears into the heterophonic confusion, but it continues to contribute to the whole so that no-one is left wondering, ‘What happened to that idea’? You can hear what happened. It is important to be realistic about sound.

Time in music

AB: This brings us to the concept of time in music. Several Nordic composers have written about it and have composed works that play directly on aspects of time: the Swedish composer Anders Hultquist has composed a work that he calls Time and the Bell, and the Danish composer Ivar Frounberg has written a work with the same title. Another Danish composer, Karl Aage Rasmussen, has written a series of works that dwell on the concept of time. For a Nordic composer like Cecilie Ore, time in music is a recurring theme. There are even books published on the subject. Still, I have a problem with actually hearing work that engages with time in music. Sometimes I wonder whether it is just a theory that physically can’t be heard. Or maybe it is a theory that’s not meant to be heard in musical sound? To a listener it does seem strange to be told about formal principles in a musical composition and still not be able to hear any of them.

OAT: Music is an art that takes place in time. We should think more about time, and about how it unfolds. I find theoretical observations about time very difficult to grapple with, but they can result in interesting music. You can’t hear the Gregorian song in Perotin’s work—it operates in theoretical time. And you can look at composers who have tried to make these stunning, fast, flickering-pieces—like Mendelssohn in his age. Despite the fact that his music is incredibly fast you can still make it out. Yet I believe that at the time many people thought his music had reached the limit of what could actually be perceived. It’s amazing to think of how original his scherzo movements really are, but then after that, music simply got faster and faster. Composers now put an enormous amount of work into a particular detail that may contain a completely correct row but it is played so quickly that if you blink you’ll miss it. What’s the point? You could just as well have written a ‘grace note’ instead.

Take Beethoven. He became deaf, but one of the things he was able to discern was how to stop time. You can hear this in the Overture, op. 124, Die Weihe des Hauses. He is reading a Handel overture and anticipating what’s going to happen on the next page and enjoying the reading. This pleasantly suspended moment is the result. Throughout this weird overture he is reading Handel with his own strange sense of warped time. It is the same in the late string quartets; they are so slow that no-one had composed anything like them before. It wasn’t until Beethoven became deaf that he began to work with theoretical time. There is a limit to how far theoretical time can be stretched—you also risk the engine beginning to spin in neutral, at which point it becomes nothing more than an interesting idea. I prefer to stay within the boundaries where I can actually experience time.

It is part of the way we view things in sonology; we are not conservative, but we have criteria. You have to be able to hear what you write. Many of our students today think that it is irrelevant and many modernists have thought the same. But in spite of that I, and a number of others, insist that it has to be audible. There is no meaning in writing music if one can’t hear the messages. The sceptics think that it’s acceptable for music to appeal through its proportions, or just on an analytical level. They take the view that you don’t have to hear every single part of the musical concept. For me it is absolutely fundamental that I can hear the ideas—I mean, if it doesn’t appeal to the ear then it is not music. How can that be so difficult to understand? I think that it is completely incomprehensible that music should bypass hearing. If you are able to work out an idea that expands the way we hear things, then so be it. But if you make something that is actually an obstacle to listening, then I simply don’t see the point of it. At the Music High School we are adamant about this. Indeed we are so strict on this point that we encounter problems with the younger composers. They are no longer interested in the position that we take on this. The pendulum is about to swing again, but I won’t abandon my point of view.

AB: In your music aren’t there apocryphal references and hidden quotes?

OAT: I’m not sophisticated enough for that. I’m not particularly intelligent, if I had been, then maybe. I struggle so hard with composing, and if you can’t hear what goes into it then I don’t understand why one writes it at all. When you hear a piece for the first time, there is inevitably a lot that you don’t understand. You’re left saying, ‘What on earth?’ Then, once you’ve heard the work a few times you’re left feeling ‘Yeah, uh-huh, that’s what it’s all about’. Yet everything was actually present in the work from the beginning. The problem with much orchestral music is that people aren’t used to listening to so much counterpoint at one time and as a result they think it’s just a big mess. But that’s not the case. There are some incredible carefully thought-out relationships and a lot going on at the same time. There are many people who think that orchestral music is difficult to listen to. It demands a ‘lateral’ way of listening.

AB: Polyphony, being multi-layered, is important to you, but sometimes it is perceived as chaotic. It’s a terrible situation to be in when you yourself can hear it, but your audience . . .

OAT: I hear it, that’s why I do it. That’s why I have composed a piece called Please Accept My Ears, where I ask my audience to consider the notion that there is possibly something wrong with my hearing . . . because I do hear all these things. In the viola concerto, Ved Komethode (At the Head of the Comet), I tried to make etchings of specific structures—they are not completely ‘focused’, but the piece I am working on at the moment is completely focused. I have called it Im alten Stil (In the old style) because it is written in my old style that is completely focused. It’s like the horn concerto, Beyond Neon. But where development takes place in the viola concerto there are smears . . . the placement of the layers is very important, but the elaboration is a bit more diffuse. This is something that I have begun to work with lately. It is more ‘out of focus’ so that you get less detailed landscapes—sounds that are not quite as sharp and distinct around the edges. It is a style of smears in which I etch these structures instead of focusing them.

AB: In other words a kind of palimpsest where you can see that you have erased the original lines, so the earliest form isn’t clear any more?

OAT: Yes, as if, for example, you were to make a very clear painting and then take your thumb and smudge it, that’s what is presented. It creates a very diffuse and quite exciting atmosphere. There isn’t as much structural argumentation as there used to be when you could discern the influence of Hindemith and neoclassicism in music. Now if you smudge that, the argumentation becomes less intrusive and is a little more interesting, not so excessively obvious. That’s why in my new orchestral piece I am trying to make a sound that is super clear, just to be able to say that I have now finished with doing that once and for all.

It’s interesting that when I tried to compose an opera I had tremendous problems. You hear so many different and new approaches to opera, with Sprechgesang techniques and so on, that I decided in my third opera to compose an opera in the way that Wagner did. At the time that he criticized Italian opera he had composed one himself, namely, Das Liebesverbot, a pure Donizetti-style opera, in fact. He was familiar with what he criticized, which is important. When I criticize operas and librettos then I feel the need to write one in order to understand what is involved; in order to avoid creating such a thing again.

I did that with my new work. I couldn’t stand any more of this kind of super-focused ‘tuttelut, tuttelut’, so I wrote one final work in this style to get it out of my system. You can’t sit and bullshit about a form that you don’t actually understand yourself. So Hertuginnen dør (The Duchess Dies) is a text-based opera with dialogue and so on. It’s a quasi-baroque opera, a meditation on baroque operatic forms, and it actually works quite well. It has set-piece ‘numbers’, with arias, ensembles—everything. Precisely what I think opera should not be.

AB: And you think that it works well in any case?

OAT: On yes, yes. It does. It always has. But I think opera should be something else.

AB: What?

OAT: I think opera should be more like what Luciano Berio did—a kind of dream world with a mixture of all kinds of arts, dance and what have you, so that realism is completely dispensed with. Instead, one creates a panorama of mental states, the experiences of dreaming. My opera The Hermaphrodite is like that—a series of scenic hallucinations. The production could be very interesting, and one could do something interesting with the orchestra as part of the scenario. There is a lot one could do, if only one were allowed to.

AB: I get the impression that a part of your aesthetic goes back to futurism. To what extent does your approach to music find its roots in the movements at the beginning of the century?

OAT: There’s certainly something in that. It is only recently that people have discovered how many incredibly exciting things happened around 1910. For me it began with finding out about all the music that was created during the French Revolution. I discovered Étienne-Nicolas Mèhul (1763–1817), François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829) and many others that I had never actually heard of before and who are quite brilliant composers. Suddenly you see Berlioz in another light, and realize that he wasn’t as strange as everyone thought.

Beethoven was actually influenced by Mèhul and others who invented the French Revolutionary style. The classical style was developed during the French Revolution. We thought we knew a whole lot about futurism, but I got a recording several years ago where they had reconstructed all of Russolo’s machines—the noise generators. Then there appeared a piano transcription of Luigi Grandi’s Aeroduello from 1935 that I can’t remember ever having heard before. Music like Sacre is just a part of this movement. Suddenly you find out that this belongs to a huge world of ideas that have since been forgotten! And now Soviet Futurists like Vladimir Deshevov (1998–1955) are being recorded and a recording of Mosolov’s Piano Concerto, some of the strangest music I have ever heard, is being released. Then there is someone like Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893–1979), who composed microtonal string quartets in 1923, and George Antheil—not only his Ballet Mechanique, but also his piano and violin sonatas which are completely crazy and which could have been written today!

Now these things are being released on CD we can begin to get a picture of what actually happened at that time. The 1960s are only a kind of shadow of what went on earlier. The 1960s saw a massive movement based on the ideas that were founded in 1910. Now you can truly see what it consisted of. I listened to the Scythian Suite by Prokofiev and a number of other astonishing works and realized that they were part of a whole series of compositions from that period. Respighi, whom you don’t think of as a Futurist, was one in fact.

Film music was the continuation of the Futurist movement. Max Steiner’s King Kong is futuristic music, heavy orchestral wheels that grind round and round. Likewise Waxmann’s Bride of Frankenstein which is in precisely that style. You can begin to fill the lacunae in music history. The period before the First World War leading up to the 1920s were extremely significant. There are many ideas that we haven’t yet grasped. There was a woman named Louis Fuller who danced an ‘electric dance’ with phosphorescent lights, and she went to Marie Curie so that she could find out how to apply radium to her costumes in order to create more dramatic effects. The poisonous radium contaminated the audience and everyone died three months later. Here is an artist who left a mark!

AB: Did they die?

OAT: Probably. They were certainly contaminated by the radium, and they died of poisoning. They didn’t have any idea what it was, only that it shone and was very beautiful. It was a completely crazy time. There is a lot that I read about now, that I didn’t know about before. Until now, music history has consisted of Schoenberg, Webern and so on, but that was far from being the whole story. A great many fertile things happened, not least the connection with the Russian Revolution and the freedom that it initially represented. There was an explosion of experimental music. The recordings of Russian piano music of the 1920s are now available, including one by Arthur Lourié (1892–1966), a mind-blowing piano piece that goes beyond Skriabin and his type of tonality. It has become much easier to approach music history from perspectives other than the established conservatory versions that only recognize the imitators of Schoenberg and Webern. There are many other ideas that can be developed and I think it’s strange that not more is done about it. There is a mass of ideas simply waiting to be taken further.

Norwegian musical life

AB: We began this interview talking about the music history of Norway and national romanticism. You went out into the world like Askeladden, possibly to find yourself, and then you came back to Norway. What did it look like? It was undeniably a rather barren musical landscape that needed to be cultivated. How did that happen?

OAT: Oslo is the only place where one can study music composition in Norway, so all the compositional ‘cases’ come to us. It has been really rather cozy. It has been our privilege to have the opportunity of teaching talented young people. We have some very exciting composers in Norway now, it is not as barren as it was. We have made a kind of impact on composing and the composers now talk to one another, not least because of the Music High School. They meet each other as students and that makes the milieu much friendlier than before. There has been a colossal improvement. There are now several generations of composers who are genuinely interested in travelling abroad and they need to do this to get further training. Many travel in order to become familiar with the world of the arts and to find out where they stand.

AB: I am aware that a very fertile milieu has grown up in Oslo in the last twenty years. But before that, when you came home in the 1970s there was no such thing as a degree in composition, nor an institution functioning as a music conservatory.

OAT: No, but there were people like Ole Henrik Moe who went unrecognized even though he built up the Henie-Onstad Museum to a level which attracted musicians of international standing. And it was not so long after I came home that we had the visit by Stockhausen and his improvisation group that I mentioned earlier. Kagel came several times because there was enough money to invite these people. It didn’t take long to achieve an improvement.

What about Arne Nordheim who had worked at the electronic music studios in Warsaw? Wasn’t that significant? As far as I know, you have never composed electro-acoustic music. One usually has some role model either to sympathize with or to revolt against. He must have played a part in all of this?

Of course. He was very kind to me from the beginning. I was invited to visit him early on, indeed I was accepted into the music world very quickly. I was elected to the governing board of the Composer’s Union, and as a result I was initiated into all the issues and understood how Arne was trying to organize things. He paved the way for many composers. I sat on the Board of Directors the whole time he was President of the Union. Arne has had a great impact as a cultural leader and as an organizer. Now he has retired somewhat, but at that time he was always there to assist colleagues and was very generous. I don’t underestimate that.

He changed styles rapidly. Suddenly in the 1960s he developed a beautiful, relatively mild style. But he had a reputation for being a ‘pling-plong’ composer for a long time after he stopped composing electronic music. Now he writes music that is in no sense difficult to comprehend. I don’t know if he has become a moderate, but he has adapted himself to a situation.

AB: There’s an implicit criticism in that last comment . . .

OAT: It’s difficult to speak about close colleagues, but I think that Arne has found a solution as a composer: he explores familiar formulations. But it’s hard to say where the distinction lies between style and that which you quite simply have heard before. To my mind his music lies on the borderline; for example, there is a great deal that I really admire in the Violin Concerto. However, I think that as an organizer he has paved the way for us. There is no doubt about that and we are very grateful to him. Before the war, the artist as an individual had a position in society, he was asked for his opinions and was actually listened to. That role was destroyed by the artists who became associated with Nazism. Every artist who tried to step forward was met with ‘No, we’ll be damned if we bother to listen to that fascist nonsense’.

That was the attitude that Arne encountered. ‘Don’t come here with your confounded artist-stuff’ or ‘pling-plong’. But over the years he has been so consistent in his views that he has achieved a moral position. When things take a turn for the worst he is listened to. For example, there was a time when there was a threat to reduce the funding for the Norwegian Music Information Centre. At first I was asked to become President again, but then I didn’t hear anything more about it. Eventually I was told ‘No, no, too bad, but we have had to ask Arne to do it again, because it’s really serious this time’. So I knew that they had really dragged in the big cannon—not the little one—and were taking aim, PANG! They got the big concession right away. I couldn’t have done that at all. Arne can be of use in situations of crisis. The position that he has created for himself is really impressive. We have very few like him in Norway. Think about Sweden where they have Bergman, Lidholm and so on, or in Denmark, where you had Poul Borum and several others. In Norway Grieg filled that role, Bjørnson, Ibsen (like Strindberg in Sweden) also filled it, but since Johan Borgen and André Bjerke there has been no-one like it in Norway. Perhaps Odd Nerdrum, but that is all. When, for example, Dag Solstad tried to take a moral stand over a polemic topic everybody screamed ‘Damned if we’ll listen to an ex-commie’. That’s still a cuss word. There are very few who have stood up and said something that society needed to hear. But Arne has been able to do this. He has resurrected the role of the moral artist who is worth listening to. We are grateful to him for that. Others have only become celebrities—harmless, but when Arne says something about Norwegian culture, it gets heard.

A new artistic role

AB: I met you some years ago in Berlin where we talked about East and West. You spoke tongue-in-cheek about the situation earlier in the Eastern countries (O.A.T., carried away: ‘Yeah, the good old days’). It was a provocation, or at least, mind-provoking. Are dictatorships good for the arts?

OAT: No, not at all. I was really exposed to something very dramatic when I studied in Poland. Let me tell you a crazy story: I got to know an English composer who was really nice, Nigel Osborne. We were students together in Poland in 1970 and became very good friends. Osborne married a Polish woman who worked in The British Council and he tried to get her out. We arranged some improvisation concerts with a group we had formed in Poland together with some Polish composition students. We travelled around performing some chaotic concerts and gathered rather big audiences. The audiences were ready for that sort of thing. Then the authorities began to dislike the fact that we attracted so many young people, so they tried in different ways to discredit us. One evening, they knocked me down and broke my tooth, while Nigel found a uniform in his collective. He said to me, ‘I have a uniform lying in the apartment. I don’t know where it came from’. I thought that was strange. At that point (1970) we were so afraid that there was going to be a Soviet invasion that I had moved into the Norwegian Embassy. I had telephoned the Norwegian Ambassador and said, ‘The Norwegian colony is hereby about to move in’, and they said, ‘By all means’.

We all sneaked over to the American Embassy and sat and watched Mickey Mouse films in the cellar while we expected the Russians to invade. It was completely insane. But then I mentioned that Nigel had found this uniform. The embassy people said, ‘What! This is an obvious provocation. Do you understand what that means’? ‘No’, I said. ‘It means that they probably intend to accuse you of protecting a deserter, a Polish deserter. This means five years in prison. We have to get you out of here this minute’. I realized that this was the time for me to leave, but it took a month and a half for a foreigner just to request permission to leave; it was completely surreal. ‘You have to get going right now’, said the people at the Embassy, and so the British Embassy was contacted. At the time the matter of the stray uniform was being dealt with by the police a different ministry was taking care of our exit visa. We prayed that there would be no contact between the two. And since the exit permission arrived before the charge was ready, we got out of Poland.

There are many such stories; it was a completely crazy, surreal and stressful time, like a black comedy, literally speaking. It was like living in an art work, a surrealist one. The good old days consisted of a work of art, a morbid one. I was there for only one year. It’s unbelievable that people could accept such a situation, but they lived with it for forty years. At the end they said, ‘We don’t have time to dream this dream any more. We have no food, we have nothing. We have to stop!’

Now it is altogether different in Poland—in any case, it does not consist of that surreal dream anymore. But art did have a truly large position in that society, because the society itself was an artwork, so they could use the arts to comment on the artwork. There wasn’t much else to do anyway. There were good reasons for art gaining such an important position, precisely like Norway during the war. Nazism was also a kind of surrealistic performance art-work—possibly more brutal, but quite similar. There too, art was of immense significance as a weapon of opposition.

In today’s society, aestheticism is misused by being applied to politics and consumption. Instead of applying aesthetics exclusively where they belong — to art. You gain aesthetic experiences from all levels of society, so that art has lost its function as the primary aesthetic object. Instead, everything in society has become imbued with aesthetics, for good and bad. It makes it hard to tell whether people still take pleasure in experiencing art. For many, it is no longer interesting — they prefer to experience something else. It’s a growing problem. We should think about art as something much more encompassing than simply going to a concert and sitting and listening to someone twang on the piano for four minutes and then having to clap. I think there is a need to do something more drastic with the concert experience.

AB: So we return to your thoughts on a new framework for the arts.

OAT: Yes, that the frame itself is thought of as part of the whole, because it is difficult to imagine that anyone would be interested in a simple little piano piece. You confront aesthetics when opening a packet of cornflakes with a design on it and a little doll inside. It is appalling, but aesthetic—an appallingly poor use of aesthetics. And in politics, what with the party logos, yellow and blue to identify the parties. In my opinion, it isn’t right to use aesthetics like this. It is too reminiscent of Nazism!

AB: When I asked provocatively if a dictatorship is good for the arts, it was because some soul searching works came from Shostakovitch and from the Polish composers who worked under extremely difficult circumstances. Now, there are some who think that today’s composers are downright spoiled and that’s why so many toothless works are being created.

OAT: Yes, because they don’t think of the whole process involved in presenting an artwork. One must try to see how the whole functions within a big framework in order to change it. That’s what they did in the French Revolution, I’m sure. When I was in China in the ‘good old days’ during the Cultural Revolution, the symphony orchestra was actually used as an ideological weapon. It was a metaphor of how people actually could cooperate. They were impressed by seeing a model of cooperation. I am sure that the French Revolution used the symphony orchestras in the same way, to show people how they could work together. The concerto, where the individual has to relate to the group, is a kind of abstract theatre-piece which shows people how such a problem can be resolved. Even if you don’t understand the musical structures and developments, you readily recognize the primal situations that emerge in a concerto. The soloist stands in front of the orchestra which gives its support, and which takes over some of the soloist’s ideas. All of this is ideological. You need only to think of it on a bigger scale: what does this apparatus actually mean? What is its real function? We need to return to this way of thinking instead of thinking only about construction and all its related problems.

AB: Now you are defining a new role for the artist. You are describing an extroverted approach, away from construction, a role in which the artist must consider his place in a larger context.

OAT: I think so. For I think—now being slightly moralistic—since society pays for art, it ought to get something in return, something that the citizen can relate to. The problem is that some artists believe that you have to reach everybody. I think that you have to find a point of contact and I am satisfied if I reach the orchestra. Then I feel as though I have achieved a small victory and that I have done my bit when the orchestra doesn’t get up, doesn’t leave the stage, put wigs on and sabotage everything.

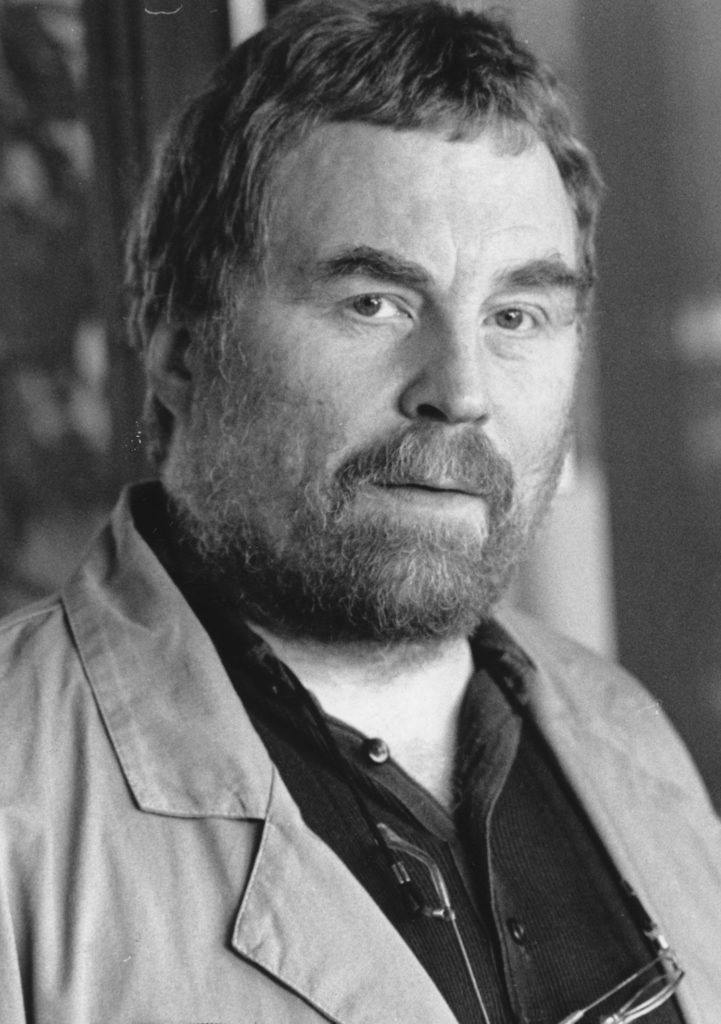

Biography

Olav Anton Thommessen (b. 1946, Norway) first studied composition in the USA at Westminster Choir College, and then at Indiana University with Bernhard Heiden and Iannis Xenakis. He completed his studies in Poland with Piotr Perkowski and in Utrecht with Werner Kaegi and Otto Laske. Currently Professor of Composition at the Norwegian State Academy of Music, Thommessen has lectured widely on music history and film music, and in 1980 initiated a course in auditive analysis (sonology) at the State Academy. Early in the 1980s Thommessen began incorporating quotations from earlier music into some of his compositions. His prodigious output has been widely performed. He has written operas (A Glass Bead Game, The Hermaprhodite), orchestral works (Beyond Neon), many chamber works as well as incidental music for the theatre. The Norwegian Music Information Centre publishes Thommessen’s scores and his music is recorded on the Caprice, Hemera and Aurora labels, among others.

© Anders Beyer 1998.

En flersporet klangrealist (A Multifaceted Sonic Explorer) appeared in two parts in Dansk Musik Tidsskrift vol. 73, no. 2 and 3 (1998/99: p. 38-44, 74-83. The interview was also published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000.

For a Danish version click here.

The interview took place at The Juilliard School in New York, in connection with the FOCUS Festival.