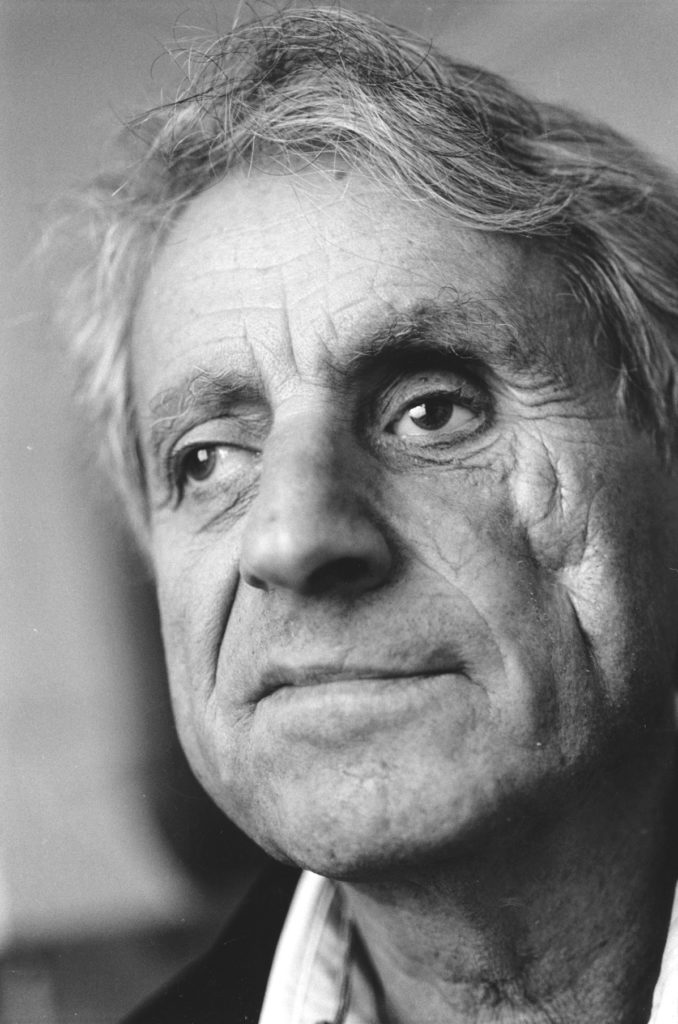

Interview with Iannis Xenakis

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: By way of introduction and in order to build a perspective I would like to know how you developed the musical language that is first heard in your landmark work, Metastaseis (1953–54). In a composition seminar at The Royal Danish Academy of Music you said that it is important to invent a new world, to see beyond that which has already been created. Your own background as a composer is unusual compared with that of other young composers. You were first trained as an architect and you were about 30 years old when you discovered that music was all-important to you. How did you discover or invent your own language and how did your background as an architect and mathematician influence your composition?

Iannis Xenakis: When I was in Greece—where I studied engineering at the Polytechnic Institute—I began to study music with a professor who came from Russia. He tried to teach me to compose in the traditional manner which I thoroughly disliked. I decided to study in the USA in order to learn more. On my way there I stopped in Paris for a while. Later I went to the USA and worked at Bloomington (Indiana University) for five years (1967–72).

After that I returned to Paris where I composed music that was inspired by traditional Greek music which attracted me greatly at that time. Then I suddenly broke with this whole tradition and launched straight into the composition of Metastaseis, which was premiered in Germany—Donaueschingen—by Hans Rosbaud. After I finished this work, I went on to another, Pithoprakta, which was premiered by the conductor Hermann Scherchen in Munich. I had found a new expressive means that had to be tested.

AB: You originally went to Paris for political reasons?

IX: I fled Greece for political reasons. At that time I was a communist and I wanted to leave political problems behind me. And, I wanted to be a musician. I had an uncle in the USA and I wanted to get away and to start afresh.

AB: I want to go back to the opening question about your development as a composer. Was it the meeting with Olivier Messiaen that inspired you to develop your completely individual musical expression?

IX: I met Messiaen and showed him some of my music. I asked for his opinion and asked if I could study with him. He accepted me at the Paris Conservatoire without asking me to take the entrance exam or requesting to see any documentary evidence of my previous studies. That was in 1947–48.

AB: In Nouritza Matossian’s book, Xenakis, there is an account of your meeting with Messiaen. He is quoted as saying: ‘I understood immediately that he was not like the others’. It seems that he consequently advised you to skip the study of counterpoint and instead to apply your experience as an architect to music. That takes me back to my introductory question: how did you work to transform these experiences into musical sounds?

IX: I worked as an architect in the firm of Le Corbusier at that time, but I always thought of music as architecture. It was interesting to create music from my experience in a context that had nothing at all to do with music. I actually worked in both directions: I created music from architecture and architecture from music. I worked with Le Corbusier for twelve years—until the end of the 1950s.

AB: Why did you stop working with Le Corbusier?

IX: Because music took more and more of my time. I would like to have continued to work as an architect on the side while working as a composer, but it was impossible. I met architects later in Paris, but I had nothing in common with them and realized that I couldn’t take up that work again, so I never went back to working as an architect.

AB: Did you integrate all the experience you had as an architect—of form, volume, surface and proportions—into music?

IX: Yes, but only to a certain extent, because architecture is not the same as music. I have experienced both and I have sometimes tried to combine them. Music is much more abstract than architecture which is based on what you can see and is experienced in several dimensions. Music, on the other hand, is abstract because it treats only the dimension of sound. In itself, the material of sound exists a long way from the experience of everyday life.

AB: Once, at least, you managed to go from architecture to music and from there back to music. I am thinking of the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair (1958).

IX: Yes, that’s correct. It was at the time when I worked with Le Corbusier. I showed him the design I had made for the Philips pavilion and he was interested. My work there was an extension of Metastaseis, which is built to a large extent on the idea of glissandi combined in various ways. I thought of these glissandi as straight lines that can be woven together in a defined space—the same as in music. They have elements in common.

AB: There is a story going around about your meeting with the conductor Hermann Scherchen, and the time you wanted to show him the score for Metastaseis. Can you tell the story in your own words?

IX: (laughter) Yes, I can. I composed the work for large orchestra and the score was very big—very tall. I met the conductor at 8 a.m. in his hotel room, where he was reading the score lying in bed, or rather, he was reading down the score. When he got part of the way down, the pages began to fall over his nose, at which point I had to take away the pages as soon as they started to tip over. It was very comical.

To my great pleasure Scherchen liked the score very much. He said that it was the first time he had seen such radical music. As you know he did not premiere that work, but, rather, the next one, Pithoprakta, a Greek word that means ‘actions determined by probability’. This is the first piece in which I tried to work with the concept of probability.

Dialectical transformation

AB: You spoke earlier about the glissandi in Metastaseis. There was a middle section in the work, or rather, there was a central portion that used serial technique. It was not long after the premiere that you took that part out. Why?

IX: At that time serial music was something very important, something one had to relate to—particularly because of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. But I never became an adherent of serialism. I borrowed some ideas from serial music, but the work as a whole is based on ‘actions determined by probability’.

AB: In the score you describe the musical process as a ‘dialectical transformation’. What does that mean?

IX: In this context ‘dialectical’ means that there are elements that struggle against each other. This struggle has to lead to a new ‘place’, a new musical situation. In a broader context dialectical transformation as a guiding principle can be seen as a result of my interest in the old classical philosophy, especially Plato.

AB: We shall return to classical philosophy, but now I would like to dwell a bit on the early part of your output. After the two orchestral works, Metastaseis and Pithoprakta, there was a long period (1956–1962) when you refined the formal aspects of your compositional technique. I am thinking particularly about its theoretical foundation. You also began to work with the computer as a tool.

IX: Yes. I met a generous man who had an IBM computer and he allowed me to use a computer studio. I tried to write computer programs that could carry out the calculations for ‘actions determined by probability’ which would otherwise have taken a long time to do manually. That was in the early 1960s.

AB: You continued to work with probability, algorithms, statistics and logic as a starting point for composition. What was the real musical advantage in using these approaches? Was it to avoid other ways of determining structure?

IX: The logical principles I used were supposed to help determine logical steps for making a work move forward, but they were also used to avoid the traditional ways of thinking about music. At that time I studied mathematical logic and tried to use mathematical thought processes in my music.

AB: That was about the same time that Boulez did the opposite: he predetermined all the musical parameters in his Structures I for two pianos. At that time Stockhausen was also working with refining serial techniques. Did your music develop directly or indirectly from discussions with Boulez and Stockhausen at this time? Or did you feel you had to ignore their music completely?

IX: I did precisely the latter. I couldn’t follow the same paths as those two composers simply because I was not interested in working in the same way. I worked with theories of probability and tried to create music from them. I was not at all interested in being ‘serial’ or anything like that. I met Boulez and Stockhausen, but we soon found we disagreed about everything.

AB: Did you have aesthetic and theoretical discussions with Boulez or Stockhausen? This was, after all, the time when Darmstadt was considered the centre for such discussions?

IX: I had discussions with the Italian composer and conductor Bruno Maderna at Darmstadt. He conducted my music there, a short piece for orchestra, Achorripsis, which means ‘to throw sounds’. This work is also completely based on probability. In Pithoprakta, the material was ‘richer’ because I could much more easily imagine musical sounds without working strictly with probability.

AB: Your later music can sometimes sound as if you are working intuitively with the material. You became more adept at working with algorithms as a technical means, and so the calculated forms do not sound so rigorous anymore. One can even hear sound elements that have their origins in folk music. In Jonchaies from 1977 the melody is based on a Byzantine folksong.

IX: I do not remember that work anymore.

AB: You don’t want to remember that work?

IX: No, I quite simply do not remember it.

AB: But isn’t it correct that old folk music traditions have been allowed to infiltrate your music?

IX: Maybe. But my goal was not, and is not, to renew music from earlier times, neither old music nor traditional folk music.

AB: It is commonly believed that composers in Darmstadt in the 1950s and 1960s were not interested in having their music played for the public, that they only composed for themselves and each other, that they experimented and just wanted peace in order to compose. This myth is often repeated. What was your experience at Darmstadt?

IX: It was a place where promising young composers could get their works performed and discussed. Among others I met Nono and Maderna there. Perhaps the composers were so involved with their work that they didn’t seem interested in the public. As for me, I was never an insider at Darmstadt. I felt most at ease outside, so to speak. I could not agree with the monolithic aspects of musical thinking that issued from Steinecke, who was director of the Darmstadt Institute. The theoretical departure in Darmstadt was serial music. I was no serialist. In that way, I was much freer than the others. I had a job as an architect, was free, and could allow myself to be out of step with the others. I wasn’t forced to follow the Darmstadt serialists.

AB: You have said that you feel very close to Brahms. You feel yourself closely bound to his music. Could you explain this relationship?

IX: No, I can’t. I can only say that my feelings and thoughts are closer to Brahms’s way of creating art than to that of any other composer. There is nothing more to say. Why? I don’t know.

AB: Brahms did not compose as you do.

IX: No, I know that. Perhaps it is exactly for that reason that I admire him (laughter). No, I think that his manner of making sound, of creating structure is very stimulating. That does not mean that I want to be like him.

A new world

AB: You have also said that a composer must create his own musical universe, a new world in each work. You expounded on these demanding principles at a seminar for young Danish composition students. However, I would maintain that I can recognize a work by Xenakis—there are definite characteristics that make one think, ‘This can only be a work by Xenakis’. Perhaps you can elaborate on what you mean by ‘completely new’ with regard to your own works?

IX: I find that a difficult matter to explain. Each time I write a work, I have to forget the previous one and the experiences I had while composing it. Sometimes I am successful, on other occasions I am not. Some composers try to take things from the past that you can neither see nor hear, expecting them to reveal themselves, to become alive in a contemporary expression. Where does this compulsive behaviour come from? It relates to the concept of ‘renewal’. Some people want to retain the past in art, but also want it to be completely new, which is impossible.

AB: So you don’t try to create a connection between the past and the present?

IX: No. Aristoxenes’s theoretical works were based on musical scales. His relationship to music does not have much to do with contemporary thought. The past belongs to the past.

AB: When I asked, as I did, it was in fact because you actually gave your work Greek titles that come from another time, indeed from the distant past. How does that relate to what you have said about renewal?

IX: The ancient Greek language often contains a condensation of meaning. That’s why I use Greek titles, while, for example, ‘sonata’ says less to me. In all of my titles there is a seed that expresses the music or the principle of the music.

AB: An example of this . . .

IX: Pithoprakta. The title, as I have said, means ‘actions determined by probability’. This work was about precisely that. Metastaseis dealt with ‘changes’. ‘Meta’ means ‘that which comes after’ and ‘statis’ means ‘static condition’, hence: the movement from something to something else. This was created by means of glissandi. A glissando is perceived in such a way that you cannot experience a single momentary phase, for you are constantly on the way to somewhere else. There is a regulating flow that can be described as a movement. One can say that a row of points is connected and makes a continuum.

AB: You speak of movement and of glissando as contributing to the development of the music. Can you explain the perception of time in music in general and the concept of time in your own music in particular?

IX: When a composer writes music he uses time. That means that he has the possibility of creating time in his own way. In some cases it goes very slowly, and in other cases it is very complex, and time can be full of ‘things’, multiple layers, for example. Music is something you can repeat, but time is irreversible. The ‘problem’ with time in music is the notation of it. Time is always there, in every direction—even in the wallpaper we are looking at right now.

AB: Sometimes we speak of ‘clock’ time as distinct from ‘experienced’ time. Is that something you also work with in music?

IX: One has to work with clock time, or real time, if one wants several instruments to play together. Aside from this, clock time is in reality changeable, something without boundaries, undefined when you listen to music.

AB: For example, Ligeti’s work for orchestra, Atmosphères, could be an example that shows how the sensation of time is undetermined?

IX: Yes. One could ask oneself: why do Bach and Mozart repeat themselves all the time? It is to clarify their ideas, but also because they didn’t know how to get further in any other way! They were compelled to repeat.

AB: The relationships between rhythm, melody and harmony are the key concerns of the composers that you have named. Is this something that also affects your music?

IX: One might not easily imagine a melody without a sense of passing time, one note follows after the other. Now, you could say that one could repeat the same note. If that were the case, one would be in a different situation—one doesn’t move, the music doesn’t move from that place. You could possibly say that that is enough, but I am sick and tired of the kind of music that does not move. It’s the same with respect to harmony. It is possible to repeat the same material, both with orchestral and computer music. Time and the events in the music, create a number of actions. I experience harmony like a chain of events. It is natural for people to experience change in the course of time. Harmonic changes exist everywhere, not only in music. It would be fantastic if I could discover something that did not already exist. I haven’t done that yet.

AB: Do you contemplate discovering something different from that found in nature?

IX: Yes. Different from nature. Everywhere we see repetitions, or the semblance of repetition. The repeated patterns in the wallpaper are not the same even though they look alike. That is the reason that we in the physical sciences are careful to ascertain whether we are speaking of a change or not. Changes can be so small that we cannot distinguish them, but they are there all the same. Nothing in the world is stationary. Heraditos said, ‘You cannot cross the same river twice’. He meant that even though it is the same river, it will have changed and as a person you too will be a little different.

AB: So, correspondingly you try to create a constantly developing music?

IX: It is a natural thing to do. Unless you wish to oppose change and try constant repetition, but this gets tedious after a while and the listeners also get bored after some time. They want something else.

A new computer system

AB: In 1966 you developed the concept of the UPIC (Unité Polyagogigue Informatique de CEMAMu) which dealt with composing using a graphic notation that could be translated into music. Looking back at this, can you say something about the significance of transferring graphic notation to sound?

IX: Our work with UPIC was aimed at developing a computer system that could transform a written picture or drawing into musical sounds. We built a machine that ‘remembered’ the drawing. So, if a composer wrote an orchestral piece, the computer could ‘record’ and repeat it. This was achieved in Paris more than twenty-five years ago. With this tool the composer could test his theories, hear if what he wrote worked, could change it, and so on.

AB: Did this scientific work take place at the same time as the people at IRCAM were working to develop similar systems?

IX: No, they were much later. They were behind with respect to our work!

AB: From the tone of your reply I can imagine that there was no semblance of cooperation between you and those at IRCAM.

IX: No, there wasn’t anything like cooperation. Boulez was Director of IRCAM and he did not want to have me there.

AB: Why?

IX: I don’t know. Perhaps it was a matter of different personalities, a question of having to determine the profile of IRCAM. Boulez wished to be the one central figure.

Old and new

AB: Earlier you mentioned classical philosophy. Let’s go back to ancient Greece, to Plato, to the theories of possible society. When Horkheimer and Adorno criticized modern civilization in Dialectic of Enlightenment they wrote, among other things, on the dialectic between myth and enlightenment in The Odyssey. They saw it as one of the earliest representative testimonies to bourgeois western civilization. You too have a wide historical perspective in your thinking, and you have also criticized western social systems. Is your interest in historical figures like Plato and Lenin purely political?

IX: No. It is only partly political. I liked reading Plato in ancient Greek because I found his thoughts on the forms of society interesting. I had to think about these things at that time. After the Russian revolution it became an enormous challenge to think in terms of possible new forms of society. Not in Germany because Hitler was there, but elsewhere it was necessary to think about new forms of society, to discuss which structures were the best. Plato had a point of view that interested me at that time. It fascinated me that Plato considered all men equal. It was actually also the primary theoretical idea in Bolshevism before Stalin came to power. I found a connection between very old and very modern thought and I believed that on an ideological level they had something in common.

AB: Your political interests were gradually transformed into an awareness of structure, musical structure. Has your political engagement had any impact on your work as an artist?

IX: No. My music has always been independent of my political and sociological ideas.

AB: What are you working on just now?

I am working closely on developing the sound of strings. It has been the norm to compose for strings one note at a time. But why not have each string player produce two notes at a time? I am working on developing the musical space in order to give a richer sound to the orchestra. If you had a string orchestra with ten musicians, then you would suddenly have twenty parts simultaneously. The challenges posed by this enlargement of sound space have occupied me in my latest works and will continue to do so in future.

© Anders Beyer 1996.

The interview was published in Danish: ‘Ny musik med profil: Interview med komponisten Iannis Xenakis’, Danish Music Review vol. 71, no. 3 (1996/97): page 74-81. The interview was also published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000.