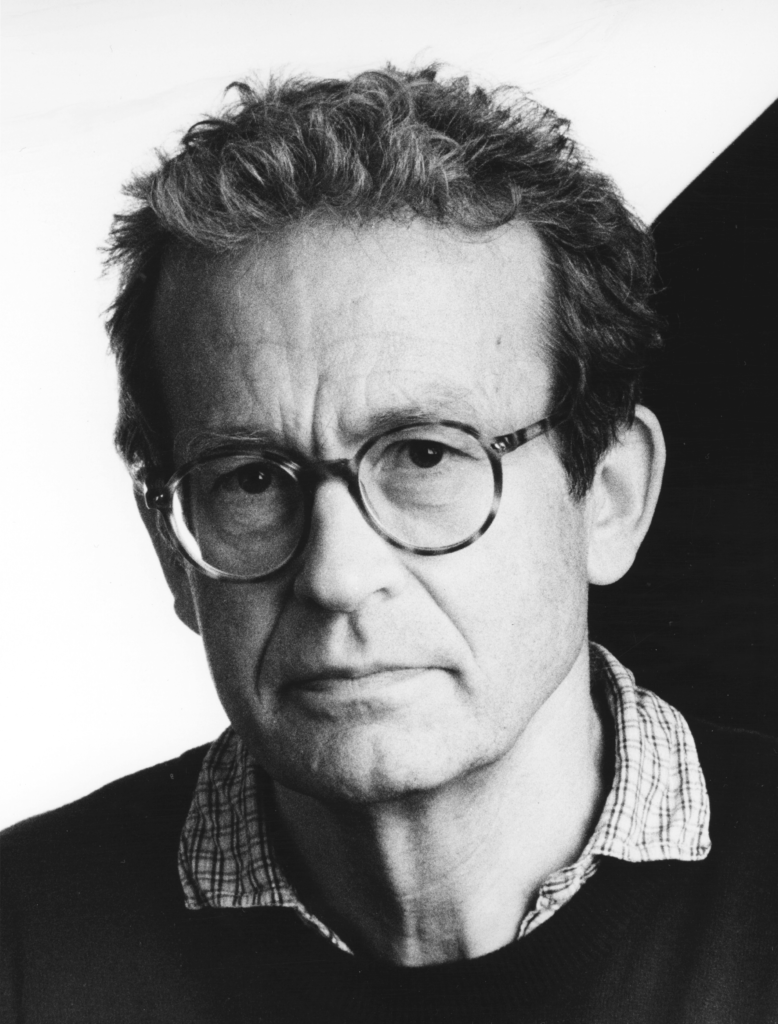

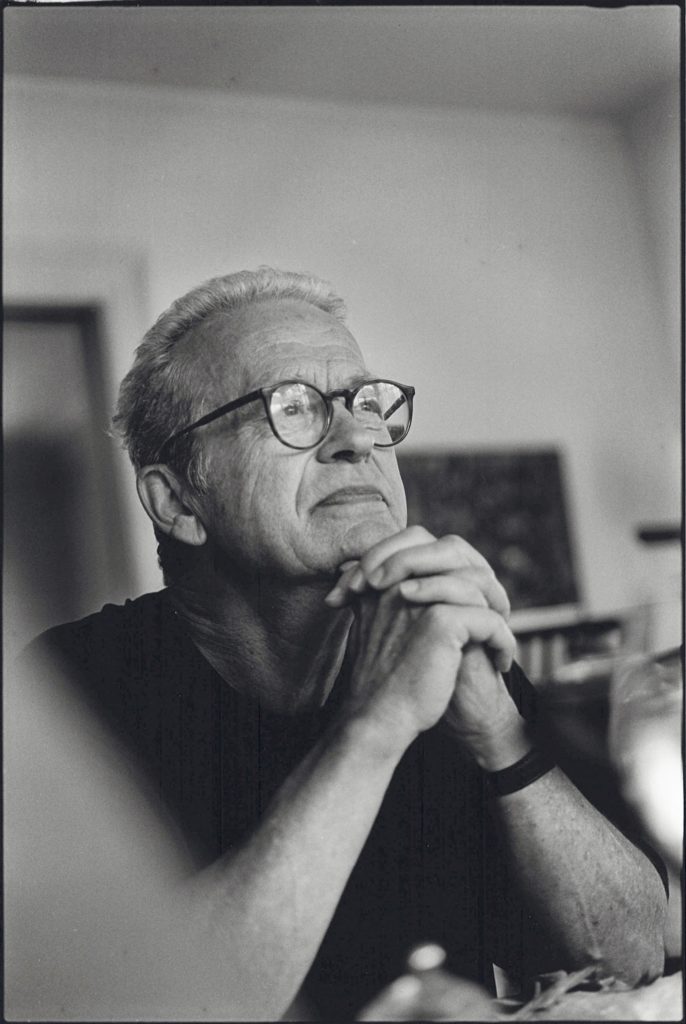

Interview with Danish composer Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen

By Anders Beyer

If someone were to draw up a balance sheet on Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen in light of his impending sixtieth birthday, then one of the points would have to be that he has consistently tried to avoid the musical mainstream. When he says his position is on the sidelines of Danish music, it either comes from a lack of self-knowledge or is an affectation, for Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen is one of the most important figures in Danish composition. As befitting his reputation as ‘established outsider’, he is on bad terms with good taste. Compromises are non-existent for Gudmundsen-Holmgreen; he shows pronounced scepticism towards the possibilities of our culture in general, and an unbending black outlook on life in particular. If one philosophy of life and art approaches that of Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, it must be the absurdism of Samuel Beckett. In his own words:

Pessimism has invaded me completely. There are Utopians who expect a new world if one only does this or that. I consider Utopias strange, captivating, stimulating for our spiritual activities—but completely impossible. One can place man on a pedestal and consider his invention and creativity to be almost divine, or one can look in vain for anything that resembles such a vision. I consider man relatively helpless and at the mercy of forces he can hardly understand. I am a pessimist because we have made so many mistakes. I am a little bit depressed on behalf of mankind. Socrates apparently had no success in convincing us to act sensibly. ‘Weaned’ in this way, I have become used to a proper scepticism concerning the high-faluting style. I don’t sing along with the Hallelujah chorus.

I was immediately captivated by Beckett when I saw his Endgame at the end of the 1950s. Since then I have read everything that he has written. With his penetratingly black outlook he sees things from the opposite side. Beckett is preoccupied with meaninglessness, which has the strange power of releasing new ways of experiencing the world. By getting rid of all that well-meaning speech one is surrounded by, and knocking it down point by point—whether it be love of God, mother love, love of children, love of love, all the things we get so crammed full of that finally we don’t know what we mean ourselves—then we end up in that catastrophic situation which has something deeply liberating about it. That is one of the reasons, among others, that I am so grateful to Cage who tore the rug out from under everything that we find dear. But the philosophies of these two do not involve complete renunciation as they continue to write. They wished to deal with meaninglessness in order to try to come to grips with it, which is, of course, impossible. But it is the attempt which counts. It reveals their humanity. The problem of form evidently becomes insurmountable. But think about what came out of it: pure, incarnate beauty. Cage said something Beckett could also have said: ‘I have nothing to say and I am saying it’.

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen was born in a house without a piano; music came into his life late. Visual art was at the centre of his childhood home as his father, Jørgen Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, was a sculptor and his grandfather was a painter. The composer’s early interest in space and material in art can be heard more or less clearly in his works. Gudmundsen-Holmgreen designs his space by means of a filtering or a grid. Certain notes are chosen to create a symmetrical structure.

The interest in space is also expressed in the composer’s fascination with mobiles. It could be said that some of Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s pieces are like musical mobiles: various objects turn around and are seen in different lights and illuminate each other in different ways. The material can have different qualities, it can be rough and obtrusive like scrap from the garbage dump, it can be soft like silk. It’s apparent that the composer has been inspired by his father’s artistic activities.

I resemble my father. That’s not so strange. In addition to being interested in space and material I have also inherited from him a sensuous disposition, a preservation of a childish mind, and hopefully, a certain innocence in my work. I think of that as a cardinal virtue. Even though existence can be unbelievably challenging with experiences that take spontaneity out of people, a certain innocence remains at the bottom of most people’s minds. I think that I have, in my association with music, preserved a bit of childish joy.

What I have also inherited from my father is the quest for the perfect form. I know that it isn’t possible, but I continue to try. I think that there is a hidden meaning in each piece, a dream that can be reached by gradually peeling away layers. In addition to that I feel the classic need for balance (it has nothing to do with the balance in music of the classical period, but is like a basic need). Balance for me isn’t ABA/ternary forms or such, but is comparable to a balancing act. I feel that my pieces are like a tight-rope act. One may be a clown on a tight-rope, ‘fall’ down innumerable times, wear big shoes and a strange hat. But yet there is something very elegant in the fact that the clown stays on the tight-rope. Among other things, that’s the situation in which I find myself with the strange instrumental combinations that I have gradually tried out: we get closer to the offensive or ‘embarrassing’ part. To write a piece for cello and car horn is not proper, it just isn’t ‘done’. This is evident from an English review, which said: ‘Performing this kind of music does new music a disservice’.

Instrumentation is important for Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen. To work with a certain gong, a cow bell or a bucket of scrap iron can take time. It’s like chewing on timbre. But even though the composer works with putting ‘found objects’ together, one quickly finds out that it’s no pieced-together collage. He wants those subtle timbres and nuances that he himself accentuates by using the old term, Klangfarbenmelodie. The form of the piece depends on which sound possibilities the instruments offer. Timbre determines form.

New – Old

Provocation, ‘embarrassment’, bizarre instrumental combinations, all can be heard in many of the composer’s works. But after all one could ask if it really is provocative or embarrassing to combine a cello and a car horn; after Ligeti’s opera, Le Grand Macabre, it can hardly be said that a car horn is ‘painfully new’ any longer.

That’s right. But this doesn’t have much to do with being ‘new’. Moreover my Plateaux pour deux is from 1970 and Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre is from 1978, Satie’s Parade is from 1917, and what about Spike Jones? It is more a question of what kind of public one meets; it can be terribly ‘embarrassing’ to show up with something pretty at a German festival. Embarrassment is a peculiar concept. It occurs when the audience feels out of place and afraid that it has fallen into bad company. I feel that sometimes I succeed in ‘curling the toes’ of both laymen and professionals—a very special honour. But it is not that I seek embarrassment, I have simply tried not to be afraid of it.

It’s clear that Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen is inspired by such composers as Cage and Varèse. From them he has learned that one can compose with any kind of sound. For example, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, in the wide Greek landscape, listened to jumping sheep and goats that had small clanging bells hanging on their necks. This polyphonic bell sound is, for example, heard in the work, Mester Jacob (Frère Jacques) from 1964. The composer explained that the peace and sensation of ‘nature’ in such a vast landscape meant something special to him, but landscape painting, naturalism, dream music didn’t. To him it sounds like Biedermeier wallpaper patterns look. How does the music manage to be a contemporary artistic creation? How do you as a composer manage to counterbalance the idyllic?

Our world is full of cacophony and infernal machinery. That I can accept: I have composed some of the worst sounding pieces in Denmark. My Collegium Musicum Concert, 1964, sounds like a wild traffic jam. I am obsessed with noise and orientate myself in it as a listener. But ‘noise’ is only one part of the issue and, well, also an old story. Serialism is also an old story, yet still young! Look at Stockhausen. He keeps on working with a way of thinking that was launched with serialism. But I don’t believe in the single-minded theory of linear development that lies behind this project, the logic of ‘given A, B follows’. I didn’t agree with Stockhausen when he made a parallel between music and natural science in an issue of Dansk Musik Tidsskrift, imposing the theories of natural science onto music. More than half a century ago Niels Bohr took a different position. He considered art and science to be complementary! That does not mean that one should turn a deaf ear to, for example, the electronic possibilities for changing sound, moving sound, spectral analysis, fractals. Personally, I follow as best I can and easily find new inspiration, thoughts, etc., but I am perhaps a little lazy, not young anymore, and no longer chasing the ‘new’.

I also think that these days there are unfortunate tendencies to become obsessed with technology, hardware and electronics. I am sick and tired of the sound of the synthesizer. There is no programme on Radio Denmark that doesn’t have a little pinched synthesizer tune—even the green environment-friendly programmes! I think that the people behind this don’t understand that they themselves are being taken for a ride. And in the midst of the concert hall’s steadily growing mass of wires and flashing screens, I think of the string quartet as ‘alternative energy’. Excuse me for repeating myself; I have said it a few times before, but I feel quite vehement about it.

And now that we are on this track: I am quite irritated by the media’s restlessness, the way they cut things up into small pieces—and significantly enough at the same time—flattening everything out. We are falling between two stools. But back to the beginning: landscapes, calmness! When I talk about calm, it’s not to be free from new situations, disturbances, far from it. For that’s what makes it possible to find your own way; it is all the strange and provocative experiences that have forced us to find our way. But calm is just as important. Who doesn’t experience a desire for calmness? Just the word, calm. It’s a wonderful word, magical, enchanting. It is an endless dream to find a little peace in one’s soul. More and more I compose music about this dream. I don’t think that it’s nostalgia.

Even today there is a steady demand for each work to formulate a new aesthetic. But this has nothing to do with your music?

Yes, but only to some extent. I think that each new work has something new in it. But how much? And in what way? The stubborn, idealizing, in many ways ‘four-square, modernistic’ tradition has had its day. But it did well, for a whole new world emerged out of that way of thinking. Music from the 1950s and 1960s that built on expansion of materials successfully developed a new world. We would not want to have been without a Stockhausen and a Boulez. I myself have been animated by their way of thinking, believed in it. We were seduced by these composers, were so captivated that we lost our heads—and ears!

Was it after a carload of young Danish composers went to the ISCM festival in Cologne in 1960?

Yes, but also earlier. At the end of the 1950s Radio Denmark presented not only these new works, but also Webern and Schoenberg, the old serialists. That was a violent shock. It was not long however, before we developed a healthy scepticism about these ideologies. There is something that characterizes most Danish composers, which is that in this whirlwind of thoughts they have attempted to find a personal solution. Obviously that characterizes any true composer and is naturally nothing particularly Danish. But I must say that this willfulness has been quite widespread among Danish composers. It is a pluralism that I think is a Danish phenomenon. This must have something to do with the markedly democratic spirit that pervades this little country. Our best composers are individualists who are not tyrannized by a clan of theoreticians and madcaps who demand something specific in music.

In certain large European countries, composers tend to gather together in groups. The French are born fencing masters; they love fencing for its own sake. Germans are idealists by definition so for them it is a matter of honour. That Danish composers can communicate with each other in spite of stylistic differences is possibly a minor miracle. It could also be due to the fortunate fact that we have a pair of open-minded leading figures. For one, Per Nørgård, who has taught generation after generation to open themselves up to whatever they might find, and who is very tolerant towards their individual wishes. In fact, to such an extent that he has been reproached for it. But then he is matched by Karl Aage Rasmussen who represents a counterweight. He disputes a little in the French manner, he’s also an admirer of the art of fencing. On the other hand, as Director of the NUMUS festival for contemporary music he allows all kinds of approaches to be heard. It is something of a patchwork festival that contributes to making us all talk to each other—and come to be fond of each other, since no kindness and no disputes are squelched. One gets rid of one’s frustrations. There are other examples of tolerance in Danish music. At the Royal Academy of Music in Copenhagen, Ib Nørholm is both obliging and skeptical; Radio Denmark is open-minded, the orchestras happily play the work of young composers, and also the somewhat older generation of composers. Just compare that with the programming of American orchestras! The press is not ideologically fixated, etc. etc. . . . the landscape is open, good to move around in.

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen has always been open to impressions from all sides, and from many artistic ‘directions’. Around 1960 there was a revolutinary period in Danish music that had an effect on Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music.

In the 1960s we met people working with other art forms and artistic directions alongside new music. Consequently paintings came down from the walls, and music came away from the instruments: Copenhagen was in a state of flux. Art was in a state of upheaval at that time. We looked at the painters and writers around us. Hans-Jørgen Nielsen was editor of Dansk Musik Tidsskrift then and he was a spokesman for the new trends. He was himself a ‘concrete’ poet, as it is called. His work made a strong impression on some of us, Henning Christiansen and me, in particular. ‘Fluxus’ was fascinating to me, but it wasn’t there that I got my real inspiration. I was more on the wavelength of the artist Robert Rauschenberg who, with his installations of ‘found objects’, created new aesthetic materials. Well-known objects were not only recycled but reborn. You could say that he collected things that one thought couldn’t possibly be brought together. But thanks to his clear vision and artistic sensibility, it worked, and not only as a provocation, but as a valid aesthetic statement. I felt in tune with Rauschenberg’s methods and his art directly affected my concepts. For instance, as a composer and a user of quotations I have become rather like a collector. That is what I was doing in pieces like Mester Jacob and Repriser (Recapitulations). They consist of gathered objects, completely finished sound objects, albeit formulated by me. That sounds perhaps unclear, so let’s put it in another way: I tried to create some object-like sounds or elements and let them intersect with each other.

Before that, in 1962, I composed Chronos, a work that was influenced by Central European modernism. But already you can sense an unwillingness on my part; I couldn’t understand why the melody had to progress in large leaps and why moving in scales step by step was a thing of the past. So I resolutely allowed doubled octaves—impossible ever since Webern’s time—in my Collegium Musicum Concerto (1964). I wrote simple melodies, so already that was in opposition to the German-French coalition. And then came the powerful renewals from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean: minimal art, pop art, Cage. As a composer I don’t go down well in continental Europe. The Cage or Varèse mentality does well in Europe because it is so ‘uncompromising’. My problem is that I am part European, part Danish and part American: I make a kind of hodge-podge music. This creates difficulties when a foreign audience confuses my intentions with provincialism or rather pure idiocy. They think I am a country bumpkin!

In Denmark too, it happens that my personal solutions are not easily accepted. It feels as awkward as an embarrassing party where people who have nothing to do with each other are invited. I take again the example of the combination of cello and car horn, which sounds like a poor witticism, or like a bar joke, but it is precisely that stupid idea that attracts me. If one thinks more about it, a car horn has its own robust charm, and I have provided the cello and horn with a precise systematic set of social interactions, structured togetherness. I have forced them into a designed ‘life style’ so that the end result is something more than a joke, namely, a meeting of two worlds that in spite of all their differences are not so incompatible that they can’t create something inspiring together. That’s the way I have been thinking since 1964. Now, the means are somewhat more discreet, but the structured togetherness is still foremost in my mind. At the same time, I want to consider the musical world as allowing all kinds of sound.

Around a sound

Much of Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music rotates; it is non-directional and shows an affinity for a minimalist language that uses a multitude of patterns. But his music distinguishes itself from minimalism in that the hypnotic, transcendental and meditative element is not central. Like concretism in art and poetry his music is concerned with a cleansing process that aims at a music stripped of the artist’s personal expressive urges. The listener must find his own way, must be willing to accept standing in one spot and to be forced to turn around and orientate himself in the landscape. This is possibly the most significant feature of music from the 1960s and 1970s. Most recently Gudmundsen-Holmgreen has been extending a helping hand to the listener. For a number of years the composer has been working with so-called ‘filter composition’, where tones are selected so as to make symmetrical structures. Is it a way of taking the listener by the hand?

Yes, one of the ways! I help the listener with, among other things, arranging the landscape in which we move around. I have worked on it systematically for many years. What’s left is a fan of pitches, which unfold from a central note through two semitones (the first one divided into two quarter tones), a wholetone, a minor third, a major third and then, in the same direction, the same intervals in inversion. A symmetry within our common note system (albeit with the addition of the quarter tones) is made in this way. I can furthermore transpose this structure, so that the system can be spread out from other pitches in the fan. Earlier there were notes that were not found at all in my system; if, for example, I started out from the note D, the notes F and B-natural didn’t exist at all. Then I began to transpose, not because I missed these notes, but because I wished to chromaticize the whole field. I needed the possibility of creating melodies in different places—chromatic melodies, at that.

I have a strange, ambiguous, feeling about melody. As I have said, childish simplicity is something desirable, but I feel at the same time that it is elusive; one can be naïve by nature or adopt naïve manners. The latter is conscious and therein lies the problem. I use the childish stuff because I love it, but I am also aware that I do it. When my music sometimes becomes expressive and exploits a pretty melody, it is a ‘found’ element, and I present it with a wry smile so to speak. There is possibly a ‘private’ feeling of being naughty in the middle of a world where new music is becoming identified with complexity: Paris, London, Cologne. However, I think that there is a basic attraction to the pure triad, in the same way that it is appealing to write a bold seventh chord. Boogie woogie makes me feel good. In no way should this be understood to mean that I am looking back—I wish to look my times straight in the eye. I’m not interested in ending up like Rued Langgaard—all negative.

The innocent layers of consciousness

When Gudmundsen-Holmgreen begins a work, he listens to multifarious material, rather than beginning with two tones and developing from there.

My problem is that I am never completely sure about what it is I am working with. In such a situation one gets ensnared by different ideas. There is disorder in the thought process from the very first; there is disorder in the beginning, the middle and the end. Problems are only augmented if work on one piece takes perhaps half a year: I am not the same person when the work is finished and I have to revise the beginning. If one, on top of that, improvises along the way, then the risk is, that some things sneak in that shouldn’t be there. Finally improvisation in itself is problematic, because the composer is limited to what, in actual fact, is often rooted in convention. It is the classic problem: improvisation builds on habitual concepts, on trained instinct. Generally I want to give intuition as much room as possible, and I have all the sympathy in the world for those concepts that are in place right from the beginning of the work’s existence—this hazy landscape of the innocent layers of the conscience. When we begin to speculate about it, we have the conflict between the unborn and the all-too-prepared, between intuition and cool calculation. The work can only succeed if there is a beautiful and miraculous correspondence between intuition and the thought-out plan for the piece. This is a banal statement but it’s nevertheless true.

In an overview of Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s production, the basic aesthetics are the same as they were thirty years ago, in his first mature works. And yet something remarkable has happened in the later works: a more organic and flexible procedure is evident, more artistry is included.

The tough period in the 1960s with the anti-art, point-zero search on one side, and serialism on the other, is history. We have now opened doors to new trends, first and foremost, because the musics from the East and from Africa have been drawn into the music of the West and have provided a new range of sensuality. I believe absolutely in musical presence. You can hear it in the string quartet in Concerto Grosso; it behaves with artistic refinement, but it is surrounded by some wild bodies of sound, almost a jungle. The phrase ‘jungle baroque’ has been a key one for me. So a ‘raw’ lion’s roar comes right out of the orchestra. I think it’s exciting to combine the raw with the refined, or to put it another way: ‘there is rock in baroque and baroque in rock’. Or as I have said about the Concerto Grosso: ‘Vivaldi on safari, Spike Jones in plaster’. The term, ‘jungle-baroque’, also points to an increasing interest in rhythm. African music has interested me ever since I saw an African ballet thirty-five years ago. It was one of those life-changing experiences. I was searching for African rhythms long before anyone started talking about them. They didn’t suit my work in the 1960s, so I put them on the shelf.

In Kysset, rituelle danse (The Kiss, Ritual Dances) composed in 1976 for Eske Holm’s dance theatre in Pakhus 13, I quoted a number of small motifs taken from a book on African music by the musicologist A.M. Jones. With help from an African master drummer he managed to write down whole pieces in score! A singular achievement at the time the book was published. Since then I have allowed myself to indulge in a more rhythmic ‘profile’. In 1977 I wrote Passacaglia for tabla and a little ensemble in the African meter par excellence, 12/8. In my latest works it pops up again—more rhythmic interest. Most recently I have wanted more ‘music’, so to speak. I want the musicians to project their musicality to a greater degree, to have more chance to enjoy sounds, rhythms and intervals. That’s my dream: to be able to join asceticism and ecstasy.

© Anders Beyer 2000.

The interview was published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000. The interview was also published in Danish: ‘En etableret outsider. Interview med Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’, Danish Music Review vol. 67, no. 2 (1992/93): page 38-45.

Biography

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen (1932-2016) studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen where his principal teachers were Finn Høffding and Svend Westergaard. Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s enduring contribution to present-day Danish music, principally his dedicated individualism and masterly treatment of form, have been constantly to the fore since the early 1960s when he played a significant part in the rejuvenation of Danish Music. His music is published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen and is recorded on dacapo and PAULA, BIS, among others.