Interview with Per Nørgård

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: You once dreamed about a music that didn’t exist, something completely different, a vision, a secret that you carried around for many years. It seemed that music was lacking something and you thought there was a need to add to it.

Per Nørgård: Yes, add, not just a little ‘chip’, but something with a definite dimension. I had a naïve, yet obviously real feeling that the potential of music was much greater than anyone dreamt. I always reacted against the kind of thinking that defined certain cultural entities and reduced life to a ‘nothing but’ formula simply because we had entered a post-religious period and were in a rational frame of mind. I felt entirely separate from my contemporaries when it came to accepting the prejudices of our times. I could not subscribe to the nihilism that was taken for granted those days. I had the feeling that there was a potential in music that was unexplored and was wholly fantastic.

So, at an early age I imagined a completely different music—one in which every single note was actually a part of several melodies so that in a way the notes in a large infinite whole created one melody. All melodies actually emerged from the same enormous stream, a kind of illusion of a line that in fact was only a point, but one that continuously showed new facets of itself. I imagined a music woven from one such note that seemed to change frequency. It was a vision I didn’t dare to talk about to anyone.

Actually I had a recurring nightmare that left me shaken the morning after. I knew only that something had happened. I am in a house high on a mountain, actually a house by Jørn Utzon—at the time I didn’t know any of Utzon’s buildings, but your description of your stay in the Utzon house on Mallorca reminded me of that one. Deep casings, nothing on the white walls, a glowing light from the sun and the bright blue sky outside. I am alone. There are two rooms and I am in one that is empty. I go into the other and there is a large black grand piano. As I go toward it I know that that is my destiny, and then, it ends. Everything is possible in a dream, so it sounds inconsequential when I describe it. There was a particular illumination—some supernatural colours and light. It wasn’t ordinary at all, more like some sort of torch. I was fourteen years old. The dream recurred a year later. Exactly the same. The same room. I was there, and went to the adjacent room, and there was the grand piano. I swear that it was like a film clip that was replayed. Not only did the light burn just as strongly, but it was exactly the same dream again! So in one way or another it must have confirmed my belief that I was a composer.

AB: Did you consider it a dream of destiny at the time?

PN: Distinctly . . . you are moved by such a thing, and I have not had one like it since. It undoubtedly influenced me to become more self-confident.

AB: But then your vision about the single melody that contains all other melodies might make one think of the ‘melody’ you later discovered and described as the ‘infinite row’. The similarity is striking . . .

PN: That has also occurred to me. It seems that I discovered it in the course of a development that, in fact, can be traced from work to work, starting with Constellations (1958), and especially with the Studies for piano (1959). This development turned out to be the beginning of the infinite row. That is the ‘upshot’ of the dream I had as a seventeen-year-old, but it was ridiculously utopian! Any sensible person would have advised me to be quiet and to become a carpenter.

AB: If we were to trace your development from the time you were about seventeen years old and decided to take up music, until about the time of your debut concert, we would notice something that was present from the very beginning: you have always moved about on ‘inclined planes’—so to speak—and have described your situation as being on a slippery slope. Just as soon as you have established one style, you break with it and find a new one.

PN: Yes, that’s right. On one hand you may say that unlimited irresponsibility is the hallmark of such a person: ‘He will never be loyal to anything’. On the other, you might find that it’s being faithful to restlessness that has driven me.

AB: The former is closer to how we used to think of artists, for example, from the generation before yours. With composers like Holmboe and Koppel, the person was the style. These composers discovered one path and stuck to it.

PN: I thought about music that way when I began to study with Holmboe. He had a huge influence on me. And aside from the man’s status as a composer it was a shock for a Nørrebro boy like me—a draper’s son—to enter the world of Vagn and Meta in their home in Holstebrogade, but more obviously so in Ramløse. Everything was so much grander than at my parents’ home on Greve Strand, which is more like a small-scale merchants’ Bellevue. All of Køge Landevej (the area of Greve Strand, ed.) is a kind of Klondike. It was already like that. I have a deep respect for the world of the draper, there isn’t a hint of irony in what I say. On the contrary, the more perspective I get on my parents’ life, the more I admire what they achieved. But at that time it was awfully close to me and it wasn’t my life. That I had to hold onto. ‘You won’t try to determine my life’; they didn’t either. They accepted the fact that I made my drawings and that I did nothing special at school. But then to encounter Holmboe, Ramløse and the magnificent scenery around Arresø influenced me enormously. It was like coming home in a way. Home to myself. To what I had inside.

AB: It was almost as though you were accepted into Holmboe’s family?

PN: Yes, yes. The incredible warmth. It was truly a revelation to me from the start. It confirmed the dream. I showed Holmboe my first piece, which was definitely not in the ‘Nordic style’. It was called Concerto in G Major (1949) for piano solo—not for piano and orchestra. I don’t know why I gave the piece this swaggering title, but I had an idea about the concept of the ‘concerto’ and something that ‘concerted’. It actually could be a piano solo, yes, why not? Bach’s Italian Concerto was a shining example for me in my early youth. But after looking at the notes for the Concerto in G Major Holmboe turned his head, looked at me and said, ‘I am surprised’. At that moment a connection was made between the serious side of my dream and my play world. Because actually I had just only played at being a composer. It was a typical play world. It was as if I was seeking out an older composer—that’s what Stravinsky wrote that he had done, so then I should do it too, isn’t that so? But from the moment that Holmboe recognized that there was something going on in me, it was as though I was seized by the collar. As you can see, it changed my life.

The impact of Holmboe’s world and all his seriousness naturally meant that I both started to smoke a pipe like Vagn, and began to appreciate the Nordic light over the hills of Ramløse. It also meant that I was sensitized and felt a connection with Sibelius when I heard Holmboe’s Sinfonia Borealis (1951–52). Holmboe didn’t talk about Sibelius, either positively or negatively. It has struck me many times that no-one talked about Sibelius then. What in the world made me want to study Sibelius’ music when I heard Holmboe’s Sinfonia Borealis? I also wrote to Sibelius about an organic approach to composition. I still believe in composing that way; I don’t make non-linear compositions. I have been true to that, so to speak.

If you look more closely at that period of my development you will see that I wasn’t yet traversing these different planes, but if you look back a little farther I was actually on one before I started working with Holmboe. If you look at the pieces that are unpublished—and shall remain so—for example, the Concerto in G Major and the Concertino no. 2 for piano solo (1950) that Elvi Henriksen performed, then you can see that already there is something special going on.

At that time I was preoccupied with reading Uwspenski’s Tertium organum, which treats time as the fourth dimension and illustrates it with the example of a horse that rears as it comes up over the top of the hill because it is disturbed by a tree that grows in front of it, although we know that this is the effect of perspective, etc. I was preoccupied by the infinite row—which I hadn’t yet discovered! For example, all phenomena are sort of porous, vibrating. Vibration is actually the central word for me.

When I met Elvi Henriksen—I will never forget it, she is a really pretty woman—she said: ‘There is something strange in your music, it’s like it has something new to do with time’. You know, that made me think, ‘That’s just right, now my music is getting somewhere’. And then it wasn’t going anywhere at all. Just look at the reviews of my debut concert: ‘Mysteriously unclear’, wrote Walther Zacharias. ‘A lot of notes that don’t make sense to the ear’, wrote Jørgen Jersild. ‘In any case, the young composer has made it impossible for his next work to go backwards’, wrote Poul Rovsing Olsen. The only one who really wrote that there was something unusual going on was Frede Schandorff Pedersen from Politiken. So that was my beginning.

If you look at my works from that period—let’s take the Concertino as an example—you will notice that they are completely foreign to the Danish tradition. It doesn’t fit into the Nordic tradition, it’s not in a Nordic style at all. It’s troublesome music. And entirely unsuccessful. Holmboe noticed my extreme disappointment. It is quite a shock for a young composer—I got shingles on my back the week of the performance. Besides, it turned out later that Elvi Henriksen had also read Tertium organum, so it wasn’t strange that she talked about ‘time’ in my music.

AB: Before your debut on the 17th of January 1956 you weren’t exactly an unknown quantity. Several of your works had been premiered, not least at the Nordic Music Days, where your suite for flute was on the programme. At that point in time you were absorbed by the Nordic idea: you were a Holmboe-fan, and you had even corresponded with Sibelius.

PN: Sibelius’ music was a new discovery for me—something that I haven’t got over to this day. You find places in Sibelius, for example in the Seventh Symphony, where it is almost impossible to analyse what actually is taking place. There is some form of heterophony that isn’t to be found in other composers’ works: a tympani part can just suddenly behave completely independently in terms of rhythm. Sibelius’ entire relationship to rhythm is very, very lively and unusual.

AB: Right after your debut in 1956 you got married and travelled to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger.

I travelled to Paris—and idiot that I am—I didn’t supplement my studies with Messiaen’s courses at the Conservatoire, but remained with Nadia Boulanger and went to the concerts of the Domaine Musicale. I despised all the superficiality of the fur-clad ladies in dark glasses who embraced each other. Boulez was there too. It made me sick to my stomach. Remember, I was a healthy Nordic fellow! So when Nadia said, ‘Mr Nørgård, your horizons are very narrow’, I was deeply wounded, but I have been able to see since then that she was absolutely right. But it was an alien world. Listening to the pianist David Tudor knocking on the underside of the grand piano didn’t provoke much more than a shrug of the shoulders from me. It was a style I couldn’t relate to at all. Paris was considered a centre.

Later, as everyone knows, our field of vision expanded so that today we have no world centre, but deal with multiple centres. The North today is just as good a centre as Paris or Vienna. You can’t say that what goes on in Paris is ‘finer’ than that which takes place in the North, even though they still think so in the city of cities. Now we also know more about Vienna at the turn of the century. That was a truly decadent city—beyond all others. The fantastic music that Schoenberg developed there is admirable in its radicalism and its independence from the imperial music that surrounded him, but that was different from the situation in Copenhagen. Why should Copenhagen at that time suddenly produce music like Schoenberg’s? That would have been completely absurd. Carl Nielsen’s reaction was, yes, in a way, as radical as it could have been, just like Sibelius’s reaction in Finland. Why expect everyone to go along with an ‘experiment in the collapse of the world’ as Karl Kraus described the situation in Vienna?

So when I arrived in Paris, the Domaine Musicale didn’t interest me at all. I actually kept a distance from Nadia Boulanger’s aesthetic. I didn’t admire everything she stood for. She had Poulenc and Jean Français in her studio and, although we were on speaking terms, I didn’t care for their music. Inwardly I felt like an emigrant. I had a project in Paris, but that project assumed that music should express the Nordic character and the authenticity of the ‘Sibelius-experience’.

AB: Did Nadia Boulanger help you to develop further and work with your discovery of Sibelius’s music?

PN: No. We discussed Sibelius. I tried to introduce his Sixth Symphony to her, but she was just as far removed from that as I was from Paris. She had quite a cool attitude towards him. She was generally very critical. For example, she couldn´t relate to Boulez. She said, ‘Boulez may have a language, but I don’t recognize it’. I believe she was plunged into a deep crisis when Stravinsky began to use serialism. At our Wednesday classes we usually sang through different works and then there came the terrible moment when she distributed Canticum Sacrum and a young scandalized ‘Boulanger-ist’ stood up and said, ‘Mademoiselle, I have discovered that the melody we have just sung contains twelve tones’. She became very agitated. I don’t remember at all how she explained it, but suddenly, everything that she had preached for years about the blessings of diatonic music didn’t hold up any more. But that didn’t interest me very deeply—this emigrant from the North. What did I compose in Paris? Sångar från aftonland (1956) for alto voice and five instruments! To texts by Pär Lagerkvist. That was my main work while I was Paris. So, I don’t know . . . I hardly made the most of the situation . . .

AB: If you made something of it then it might have been more in the area of craftsmanship, from a technical point of view. For example, you had to be proficient at the piano?

PN: Yes. It was marvelous to go through the ‘hard’ school. And Nadia was a marvellous reader of my music. Her ability to point out inconsistencies was unique and impressed me deeply. Her merciless dissection of, for example, the piano piece, Trifoglio, made me revise the music totally. She read the piece through and said, ‘I’m a little disconcerted’. She said it because she thought that I expressed goodbye very beautifully in my music: ‘You say a very beautiful goodbye. I find your way of saying goodbye very moving. But you can’t go on saying goodbye forever’! Now that is an awful criticism, because it indicates that a piece of music revels in a single mood and never moves out of it.

I learned a lot, like simply trying to be concise in a piece of music. However, stylistically it hardly influenced me at all. But to turn back to your idea of ‘inclined planes’: I can actually point out things that I think have always been part of my music. For a time I worked within the Nordic style with its particular expectations, for example, modality, triadic chords, rhythmic ideas, etc., a whole string of expectations. But I broke with it around 1960. There was an impulse from the beginning, but it was held in check in the Nordic world of the 1950s.

AB: Now that you are back to the issue of ‘inclined planes’ and your early frustrations, I would like to return to Frede Schandorff Pedersen, Politiken’s reviewer, who wrote about your debut concert in 1959: ‘[T]houghtfulness and emotions dominated what is actually said in the pitches. It is as if one should continually recognize a meaning that isn’t obviously projected by the composition, from the life of the notes’. And further on: ‘His first string quartet demonstrates an even, exceptionally well-founded craftsmanship, a large creative talent. Why does he then strike out to a place where anybody would be out of his depth? His future development perhaps will provide the answer’. Is what Frede Schandorff Pedersen wrote about the twenty-three-year-old Nørgård due to your wish to create a fruitful kind of confusion?

PN: Yes. It can be said very simply: I want ambiguity. I have come up with an all-purpose, general term for this simply because I haven’t found anything better: interference. Interference, or ambiguity in the broadest sense of the word, became apparent even as far back as when I made my Tecnis (the composer’s home-made comic strips with musical accompaniment, ed.). I can remember that I found the right term when I had my brother swear to our goal in life: to confuse as many as possible as much as possible. At that time it was with our Tecnis. My brother wrote the texts and I made the drawings and the music. And there was no denying that we confused the members of the family with these strange worlds. So happenings were a part of my private life—before ‘happenings’ existed. There is that ambiguity again. To introduce another view into something that someone else believes they ‘understand’. That is still my mission.

It has never been my intention to compose loose or floating forms. For example, I have never been attracted to impressionism, but rather to very precise forms that contradict each other while each is compellingly necessary! I can remember that I was interviewed by Morton Feldman in Holland at a festival in Middleburg in 1986. He apparently didn’t know what our topic was to be, but he had read something about my music and the Nordic component and he said, ‘I am a New York Jew and this thing here with the Nordic—now that I have met you and can easily see that you actually look very Nordic—could we talk about that?’ No, not really, I thought. So I suggested that we could talk about something which he had said and which I had once read and that I found quite wonderful, which was, ‘If I work with the notes, trying to do something special with them, and then I hear a weak but clear voice calling, “Help!” then I know that I should stop trying’. So I said that for me it is precisely the opposite. ‘I work with them at length—until I hear a loud and clear “Help!”’ And that is my mission: to create concise forms that provide completely clear suggestions. That was already evident in the piece I wrote as a seventeen-year-old: I create a ‘gestalt’ but it is somehow refuted by something else.

Perhaps there is a bit of Zen Buddhism there. In Zen Buddhism there are three opposing basic principles: stillness, shock and paradox. If you chose paradox as the basic norm, a short-circuit makes it possible for you to enter life for a moment and realize that it is incredibly strange. I have always felt that we undervalue what we are in the middle of and I hate it when someone explains ‘what it is we are in the middle of’. There is always more to it than we think; that is something I have ‘known’ from the beginning. Don’t ask me how I knew it. I don’t know it any more than I know where that dream came from. But I do think that this knowledge is my firm foundation.

Now that I am this old I can see these inclined planes and how they developed. It was a long time before I found the word for it—I believe it was after the Wölfli-period. It was also confusing for me: what in the world was happening? I’m thinking about the shift at the time that I ventured into the realm of the psychedelic at the end of the 1960s. I composed Rejse ind i den gyldne skærm (Voyage into the Golden Screen, 1968), Den fortryllede skov (The Enchanted Forest, 1968), Grooving (1967–68), which were the kind of ‘psychedelic works’ in which you enter some different kinds of infinite patterns. Then, after the Second Symphony it became necessary to find a rhythm that could articulate the infinite melody. The Second Symphony, well, simply flows in motoric quavers. So I followed a sober plan: music that moves in quavers all the time can hardly be the music of the future. But initially, the infinite row had to be expressed in terms of quavers—or, crotchets, minims, etc.—and when I composed Rejse ind i gyldne skærm with the first presentation of the infinite row, I thought it sounded so exciting that I had to make a whole symphony out of it. This was the Second Symphony (1970) and that was interesting enough. But I knew as I said before that I couldn’t stay in that place. I have always thought in terms of Koestler’s open hierarchies where each level is as important as another. I think in terms of whole forms that are themselves enclosed in whole forms of different kinds—and in this context I analytically explored the new possibilities inherent in the proportions of the golden section in order to avoid the persistent motoric movement of the previous works. It was simply necessary to think in new ways, and it may be that the only possible result was the Third Symphony.

So, suddenly I found myself in the hierarchical world of the Third Symphony and it was more appealing to audiences than the Second. Following the success of the Third a friend asked me, ‘So now you have arrived at your goal?’ to which I answered, ‘You have understood nothing’. It was probably then that I started to realize the significance of these inclined planes in my life. Every time I thought to myself that I had arrived at a place from which I could continue, the thought made me kind of claustrophobic. Indeed, you could achieve an endless number of pieces by just moving the ‘bricks’ of the Third Symphony around. Perhaps even compose another nine symphonies. I suppose at that moment I realized that if I did that, I would give up my basic mission, that is, ambiguity. I am reminded of a time at the Warsaw Autumn Festival when Luna was performed—a work that for me is full of interference and paradox. It was a success and people came and congratulated me. However, I was bothered by all the friendly remarks about what ‘beautiful nocturnal music’ it was. So I simply left during the intermission, went to a bar and drank one whiskey after another until I fell into a kind of crystal clear state. Suddenly I realized that I was obviously depressed, because in spite of my efforts my work was apparently still misunderstood: it seemed completely ‘comprehensible’. I had to radicalize my musical language!

AB: Let us go back to the transition from the 1950s to the 1960s, to the shift in Danish music that has been described as a radical step in aesthetics and style. For you it didn’t really constitute a break in spite of what is frequently claimed. Much has been said about the famous trip to the ISCM World Music Days in Cologne where some of you heard Pli selon pli, Kontakte and Anagramma. Presumably that was a shock for several Danish composers of your generation. But a look at your works shows that the new sounds were not so completely new to you. You were in Rome at the ISCM World Music Days the year before in 1959 and you had composed in a serial style before 1960.

PN: Yes. In Rome I realized that it wasn’t as simple as I had believed it to be when I was in Paris, and I gained many strong impressions, often from the performances of works by completely unknown composers. I could hear that here was something that I couldn’t attain with my technique. It was enervating and fascinating. When I got home from Rome I wrote a feuilleton that was published in Politiken. This article clearly shows my vacillating position. The older Danish composers and musicians didn’t like it. When one heard something like this it was quite normal and ‘correct’ to be revolted.

AB: Even though Ib Nørholm composed his Tabeltrio and Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen composed Chronos after the trip to Cologne in 1960, the long-term reaction was to adopt an extreme form of simplicity that later became known as the ‘new simplicity’. The Danes created a kind of opposition or answer to the complexity that emerged from Darmstadt, among other places.

PN: Yes. Not many let themselves be caught up in the sounds coming from the south. We were fascinated when Stockhausen produced his new Zeitmazse in the 1960s. But it wasn’t really what we had been searching for.

AB: But on the other hand, I don’t get the impression that you unequivocally separated yourself from that world. You allowed yourself be inspired and consciously took structure into account.

PN: Yes, for us the new ideas worked like a colossal x-ray—almost like an x-ray of the Danish tradition. And we became unpopular, for example, for criticizing the Danish milieu in our reviews. A new piano concerto by Koppel—as stated in my review—was a farewell from the old world. We certainly had the feeling that it couldn’t continue like that, but it wasn’t that we had come up with a new goal, in imitation—so ein Ding müssen wir auch haben—it wasn’t that: it was the soul-searching that was important.

AB: But that also meant a confrontation with the institutions, which, in your case, meant that you had to give up your position at the The Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen.

PN: I was employed at both the academies in Copenhagen and Odense. In addition, I was working as a reviewer, which was quite demanding, and I needed to continue composing. But I had been doing this from the end of the 1950s and into the 1960s. What was strangely new was that I attracted the young students, all the composition students. None of them went to the older, established composers who were also composition teachers. I had Fuzzy (Jens Wilhelm Pedersen), Erik Norby, Ingolf Gabold and Svend Nielsen. They all asked for me because they didn’t want to work with the older teachers. I realized that the instruction that I had had previously was—to put it politely—incomplete. I mean: to drink tea and sit and chat generally about music—yes, fine. But there should obviously have been seminars. Here take this, listen to it, ‘What in the world did Schoenberg do?’ We heard nothing about him. They maintained a post-Nielsen aesthetic, and if you asked about Webern you were shown a score from which anyone could see that ‘there were holes in his head’.

So, I wanted to try to get beyond that. It was against this background that the confrontations arose, and with that, the shift of the 1960s. We were no longer willing to accept older people’s versions of things. Now we wanted to find out for ourselves. This didn’t please the majority of the theory staff, which, aside from me, consisted of older men. Some were more ‘quiet’ than others, but the more vociferous of them said, for example, ‘Damn, now we will have to think things over before we let things like “workshop concerts” get going!’ Basic things such as the workshop concerts that I wanted to establish in Copenhagen—and which I started in Århus as soon as I moved my teaching there—were stopped every time by the group. And when figures such as Ligeti or Lutosławski came to Copenhagen, I had to hire them—the Academy ‘had no money for such things’. My students contributed to paying their costs and we simply arranged private seminars. So the tension was already quite intense when the ‘Ole Buck affair’ set things off.

AB: By referring to the ‘Ole Buck affair’ you mean the time when young Ole Buck was not accepted in the Academy although he had already demonstrated unusual talent as a composer.

PN: Buck submitted a piece that was one of the best that had ever been written in the history of Danish music, the Haiku Songs for soprano and orchestra. He had received the highest evaluation from the expert staff consisting of Holmboe, Høffding and Tage Nielsen. And then Buck was rejected because he couldn’t harmonize a chorale melody correctly! I couldn’t possibly accept that. I went through all the applications. You should have seen me that spring. I studied them every day. The staff in the office glared at me, but they couldn’t forbid me to read them. I made a note of all those who had received a B+ in their main course of study. Every single one was accepted. And yet the one who had received an A- was not. You may have read Dansk Musik Tidsskrift from that time when the problems seeped out into the public arena. Out of consideration for Buck, the Ole Buck affair was referred to as ‘Case X’. Riisager, who was Director of the Academy, was deeply unhappy about the situation—he was supposedly for new music—but he had to comply with his faculty.

AB: So you left the place.

PN: So I left and everything was up in the air for four days and then Tage Nielsen from The Royal Academy of Music in Århus called and said, ‘Have you any interest in coming over and working with us as a composition teacher?’

AB: This was in 1965. After the struggle in Copenhagen you entered a very fertile period in Århus.

PN: All my students ‘moved’ with me to Århus with the result that Danish music spread and became decentralized. That was one consequence. The students became teachers and active composers in Århus, and, later on, in other places in the provinces. It wasn’t very long before I suggested that we should have a new music society in Århus. So AUT (Århus Young Composers Society) was established.

AB: Slowly a whole new music scene developed in Århus. When I mentioned the institutional breakup it was because I wanted to reinforce the image of a whole generation supporting a change which encompassed aesthetics, styles and a new mentality.

PN: Yes, definitely. So what happened was the right thing.

AB: We are getting to the 1970s, and newer Danish music begins to become interesting to people other than Danes. The interest grew slowly—particularly in the English-speaking world. In 1974 came John H. Yoell’s book, The Nordic Sound: Explorations into the Music of Denmark, Norway, Sweden. He writes on p. 50 that ‘your unpredictability may lead to . . . vaporization in a cloud of mysticism . . . or, perhaps, the numbing paralysis of an identity crisis’. Yoell closes his characterization as follows (p. 172): ‘Possible seepage from the psychedelic and rock subcultures adds further complexity to this composer who seems to run in several directions at once’.

Here one could say that your tactic of generating confusion succeeded completely. Yoell seems to have been frustrated in his search for a pigeon-hole into which he can put Nørgård’s music. He doesn’t understand the concept of ‘inclined planes’.

PN: That’s right. Yoell predicts that I will end up with a personality disorder or a neurosis, or that I will stop composing. He has the most promising futures planned for me—and I have disappointed him until now. But from what we were talking about, you can easily see that there is no contradiction between what I did in the 1960s and what I was doing before. I continued to compose works in which I used the infinite row as a technique—that was my form of twelve-tone music, so to speak. But from a deeper perspective there was something else that I was looking for.

The infinite row is a result of interference-thinking. And I will never forget what, for me, was possibly the most important thing that happened in the 1960s. When I was making the electronic introduction for Babel (1965, rev. 1968), I became more and more fascinated with interference, simply and purely, physically. That was the first time I really experienced beat-tones and realized their perspectives. So I composed a work that was called Den fortryllede skov (The Enchanted Forrest) that completely depends on interference. It was in turn reworked to become the first movement of Rejse ind i den gyldne skærm. From that point on interference became more than a concept and appeared in a physical form. Later I can see that it was then, really for the first time, that I was able to pinpoint my interest: ambiguity, or interference, in the broadest meaning of the word.

AB: Earlier in the conversation we reached the Third Symphony and the encouragements you were given to continue composing in the same style. Now that work was a high point in Danish music. The Third Symphony has been referred to as a symphony that formulates a philosophical outlook on life, like Mahler’s symphonies.

PN: A ‘philosophy of life’ symphony? It is possibly that, on one level or another. But it was rather like working with the elements of the golden proportions at the core of what fascinates me. It wasn’t as though I wanted to write a symphony that presented a philosophy of life—God save us! It was more as though something grew, and because I began to work with the elements in a certain way, it finally became what you might call a ‘philosophy of life symphony’.

AB: These elements come together in an all-embracing symphony, you might say.

PN: Perhaps the concept of the all-embracing work amounts to something that can resemble a ‘philosophy’. I didn’t start with some melodies and their development; from the beginning it was the sound that was at the centre. Truthfully, it is a deeply rational work. I started with sound, with all the overtone series that ‘fall down’. It was deeply fascinating for me to work with several overtone series, with ambiguity. The overtone series is a hierarchical phenomenon! Actually it consists of many overtone rows that can be collected into one, which can be shown to be a part of other overtone series, on and on. In the course of the orchestra rehearsals I became convinced that I had a rich material in my hands. I allowed myself to trust my perception that it was just as important as any other sort of technical apparatus, infinite rows, or other things. My respect for perception had become a decisive factor because of my experience with Fragment VI, the work that was a winning composition at the Gaudeamus Festival in 1961. All the remarkable things I put into that score couldn’t be heard! It was a shock for a composer who had always assumed that one should be able to hear what is in the score. It looks unbelievably exciting. And I had made an impressive layout, no doubt about that. The Third Symphony was composed a dozen years after this experience and was influenced by my interest in the powers of gestalt psychology and my study of perception, for example, of interference.

AB: Perhaps one could even say that the ‘perpetually falling line’ in new Danish music began with the overtone rows in your Third Symphony.

PN: At the beginning of the Third Symphony you hear a very high sound—this seems to be the first time in a composition that someone consciously uses the ears’ non-linear properties, in order to create difference tones in the bass by putting many dissonances in the treble. So there is a bzzz created inside the ear. You’ve experienced the phenomenon from hearing a piccolo in a concert hall when the conditions are right and the sound gets going? Bzzz, bzzz, it goes, right? I thought that was exciting and so I made it happen like that in the Third Symphony. So all of that grandiose talk about this ‘philosophy of life symphony’ can be viewed as a matter of technique. I mean: you can analyse the whole symphony starting with the very exact, precise observation that in the first movement there is a gigantic growth process involving sound, rhythm, melody and so on, spread in the form of an arch. Finish. After that you enter a garden where detail is the focus; that’s the second movement. Well, it starts very high with a downward run of a series of subharmonics in the minor; it spirals down, and then a whole number of melodies emerges—melodies that people can hum. The Third Symphony became a work that revealed many dimensions, and—okay—in a way, you may also hear it as a kind of continuation of a work by Mahler. What’s wrong with that?

Now I come to your question: the music became too single-minded again. The reason for my life-long aversion to ‘single-mindedness’ is to be found, I think, in my hatred from early childhood of the male-dominated world I found around me—with its fascism and macho-values. I believe that the drive inside me directed itself towards ambiguity because it was, and is, the only answer to the prevailing tribal mentality with its black and white dichotomies. Towards a human world instead of a man’s world. But back to the Symphony! While it is true that in the Third Symphony, there is, for example, one rhythmic layer that uses the golden proportions grouped in two, in four, in eight and so on, the junctions are still noticeable. But actually, for a couple of years I composed works with tools I used in the Third Symphony.

I believe that that was the most stable period in my life—until I found Wölfli. On the way to the Third Symphony I composed Sub Rosa (1970), which is based on melodies from the infinite row in one way or another, and from the Third I composed Turnering (1975) and Twilight (1976–77). In Twilight I tried to create interferences between a large melodic complex that had grown up and a new one that shoved its way in after the other one was already launched. So the work vibrates, and then you hear the new one—all by itself. That way of composing can’t be repeated, so if I had not found Wölfli then I would have been forced to ‘invent him’ because I already had the commission for the Fourth Symphony from Hamburg Radio (NWDR).

AB: You saw an exhibition about Wölfli at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in 1979 . . .

PN: Yes. The author Jørgen I. Jensen wrote about my Louisiana-experience in the book that you have edited (The Music of Per Nørgård: Fourteen Interpretive Essays. Scolar Press, 1996, ed.). Jensen was a little upset about my reaction when I saw Wölfli’s drawings. Perhaps he believed that I was about to go mad myself because of my preoccupation with Wölfli’s ‘mad music’. But for my part I wasn’t really worried, for I knew that this was a moment of emancipation. I mean the world wasn’t changed by the Third Symphony. Twilight hadn’t changed the world either, nor had it changed me. There was something that did not work. As I said: it was the single-mindedness of the rhythmic idea that didn’t work, and to throw off all that hierarchic network was at that point a release. Also, I had simply to admit that if I couldn’t compose without that then I’d better stop. So bar by bar I proceeded to write the Fourth Symphony.

With the pretext of using Wölfli’s idea about an Indischer Roosengarten and Chineesischer Hexensee, I could say to myself: nobody can pre-determine how such music must be. What was important for me in the longer term was that this freedom provided a number of solutions to the ‘problem with rhythm’. By just throwing myself into a chaotic compositional condition I became more and more clear about the burning issue, namely, rhythm. As far as I am concerned one of my ‘conquests’ of the 1980s was the completely new forms of rhythmic worlds which I began to explore, such as eternal accelerandos, the ‘squareroot of 2 rhythm’. I last explored other rhythmic depths in the piano concerto Concerto in due tempi (1994–95) and in the work for two pianos, Unendlicher Empfang (Infinite Acceptance, 1997).

AB: In terms of structure and other things, would it be fair to say that rhythm has given you the opportunity to produce ambiguity where you can have different layers that don’t chafe or rub each other. With regard to the rhythmic proportions, do you take care that the layers don’t coincide?

PN: You could say that, but it must obviously be in connection with melody and sound, and so forth. There is no denying it, the gestalt is inescapable. What is deeply fascinating about rhythmic ideas is that they can attach themselves to melodic forms of great simplicity, combining to produce complex patterns—a ‘dynamic wave’.

AB: But—if I may just take up the thread of the conversation from before—even though you abandoned the hierarchical principles and the infinite row, they returned later.

AB: Yes, that’s right. It’s like the lovely image in an article you published: though I believed that I had burned my bridges, it turned out that apparently I hadn’t. Later, when I had a musical problem, perhaps a bridge might come and say ‘Don’t you need me now?’ In a sense, the infinite row popped up again as a tool; earlier, it had been the celebrated focus of attention, for example, in the Third Symphony, which is a kind of ‘celebration’ of the infinite row’s many layers and hierarchies. But later it becomes an indispensable means for realizing my rhythmic visions! Things that are tied to the infinite accelerando aren’t possible without using the infinite row as the foundation—to mention one example.

AB: I have sometimes heard you say, ‘I don’t know how I can go any further. It is completely hopeless and I don’t know if I can finish this work’. This kind of frustrated situation arises because you don’t compose with a ruler and graph paper marked off in milimetres. The whole time you are unsure where it will all end. Anyway you have always, as far as I know, been fortunate enough to find some ‘bridge’ ringing at your door . . . Can you say that you are more successful when the idea comes to you than when you have to sit and construe it?

PN: I believe that’s correct. I can never work with bars drawn in advance on the next seventeen pages—showing where the tempo is supposed to change and so on. I would never be able to do that. I would probably panic. I composed, for example, the Fourth Symphony and the opera Nuit des hommes (1995–96) bar by bar. For the Piano Concerto I had nothing more than [sings a short phrase]—and that’s not much to have for a whole piano concerto. I couldn’t get beyond that, but I knew that it contained the key to the rest. It was like holding the end of a thread and all I had to do was to keep pulling. That turned out to be correct. So at a certain point I simply began. Up in the flute when it goes [sings the part]. I liked that beginning a lot. The only response I have for young composers who come to me and ask, ‘How do you write the music out?’ is, ‘How did you start?’

There was a young composer who put the question to me recently, an unhappy fellow who apparently had set in motion many ideas which he couldn’t continue. So I said, ‘The only advice I can give you is to consider what you started with, what you wrote down—if you don’t believe in it fully, then drop it. But if you really can say that there is something there that continues to fascinate you, then stick to that! What you compose later has to live up to what you started with. You must never drop below that level. That is the touchstone. If the continuation loses altitude, then drop it.

AB: In your case the concern for the ambiguous and the many-layered indicate an interest in something more than so-called professional music. For many years you have been interested in working with amateurs. Then again, look at your varied output: you can compose a hymn like you did for the film Babettes Feast (1987), as well as music that demands complete attention.

PN: Well, yes. For example, Du skal plante et træ is sung by many Danish choirs. For me the dichotomy is only on the surface. My work has been described as consisting of different ‘layers of growth’—which is more complimentary than Yoell’s suggestion in 1973 that I struck out in seventeen directions at a time. In everyday-life you invariably stumble around in a great number of ‘layers’. But the thing with amateurs and single pieces of music comes from my vision of the fundamental idea that interference doesn’t need grand gestures. It can happen with one or two recorders. But each time there is obviously a new tension between whether it succeeds or doesn’t succeed, because each time it depends on the quality of the idea and its ability to endure. These are qualities that don’t depend on great complexity or virtuoso display. This is William Blakes ‘grain of sand’, to see infinity in a grain of sand or sense eternity in a bird’s flight . . .

© Anders Beyer 2000.

The interview published in Anders Beyer, The Voice of Music. Conversations with composers of our time, Ashgate Publishing, London 2000.

The interview was also published in Danish with some aditional remarks by the composer on the work La peur as it were, in: ‘Komponist på skråplaner. Interview med Per Nørgård’, in the book Mangfoldighedsmusik. Omkring Per Nørgård. Redaktion: Jørgen I. Jensen, Ivan Hansen og Tage Nielsen. Gyldendel 2002.

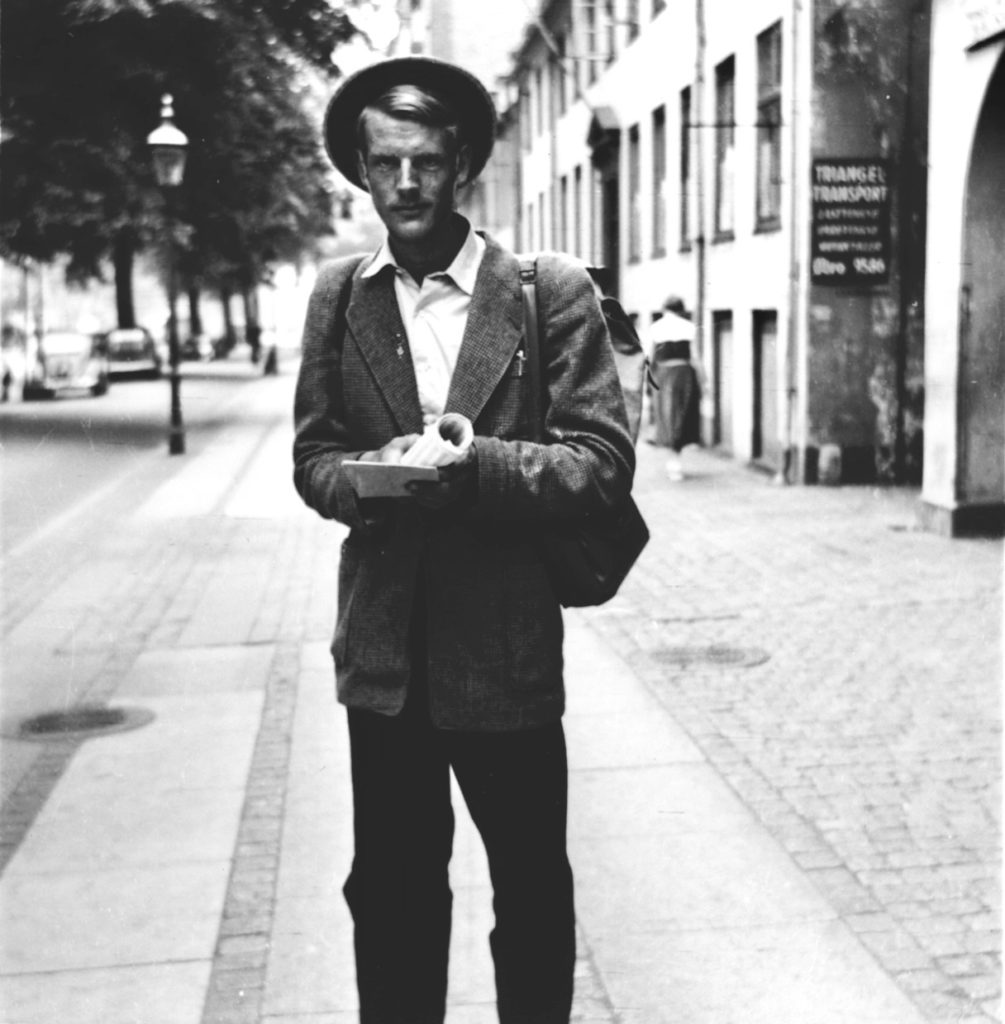

BIOGRAPHY

Per Nørgård (b. 1932, Denmark) studied composition with Vagn Holmboe and Finn Høffding at the Royal Danish Academy of Music (1952–55), and with Nadia Boulanger in Paris (1956–57). Since his return to Copenhagen in 1957, Nørgård has been in the vanguard of music development as a composer, essayist and theorist, teacher and motivator—in Denmark and the other Nordic countries, and increasingly in the international arena. Already highly regarded as a teacher, his move from Copenhagen to Århus in 1965 led to the consolidation of that city as a centre for contemporary music. Nørgård’s scores are available from Edition Wilhelm Hansen and recordings of his music can be found on dacapo, PAULA, Danacord, Kontrapunkt, Chandos and BIS.